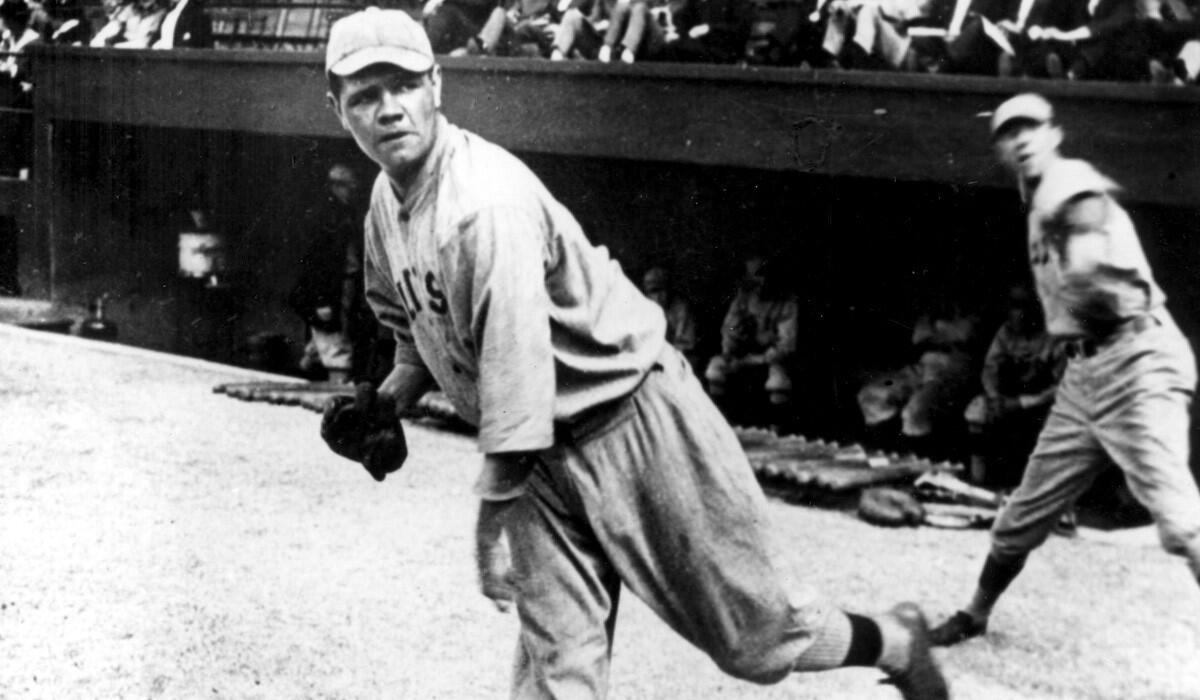

100 years after big league debut, Babe Ruth is still larger than life

It is easy now to identify the most famous name from the baseball box score dated July 11, 1914.

However, one hundred summers ago at Boston’s Fenway Park, the annotation “Ruth” was not historically significant.

The baby-faced pitcher, only months out of reform school, must have been crippled with nerves in his major league debut.

The star power that afternoon belonged to Red Sox outfielder Tris Speaker and a Cleveland Naps lineup led by “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and Nap Lajoie.

Ray Chapman, the Cleveland shortstop, batting sixth, was killed six years later when he was struck by a Carl Mays fastball at New York’s Polo Grounds.

The baptism of George Herman “Babe” Ruth, Boston’s rookie lefty, was efficient but ordinary. He scattered eight hits in Boston’s 4-3 triumph, helped at the end by two shutout innings from Dutch Leonard.

Cleveland left fielder Jack Graney, the first batter Ruth ever faced, singled. Ruth, in his first major league at-bat, struck out. He was later pinch-hit for (imagine that) by Duffy Lewis, a career .284 hitter.

Nothing on that day hinted at immortality, or the notion that a century later we’d still be talking about Ruth as perhaps the most iconic figure in sports history.

Twenty-one years after his debut, on May 30, 1935, a worn-out Ruth, wearing the alien clothes of the Boston Braves, struck out in his final plate appearance at Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl.

Between those monumental bookend whiffs he whipped up quite a dust storm.

Why are we still so fascinated?

“Because he was a fascinating person,” Julia Ruth Stevens, Ruth’s 98-year-old daughter, said in a phone interview from her summer home in New Hampshire. “He loved people, especially kids, he’d do anything for them. And he played to his audience. He was always trying to hit home runs because that’s what they wanted him to do.”

Cy Young won 511 games, but no one thought to stop the presses on Aug. 6, 1990, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his first game.

Ruth is still venerated because he combined extraordinary ability with panache and personality, in the epicenter of New York City, at the apex of the Roaring Twenties.

He invented, through his success and excess, a new term in the American vernacular: “Ruthian.”

Willie Sutton would become “The Babe Ruth of bank robbers.”

As Ruth said of himself, “I swing big with everything I got. I hit big or I miss big.”

When Ruth succumbed to cancer Aug. 16, 1948, legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice wrote, “The greatest figure the world of sport has ever known has passed from the field. Game called on account of darkness. Babe Ruth is dead.”

He died only in the flesh. His legend lived through the portals of truth, lies, myth, hyperbole, books, newsreel clips and two lousy movies (See, or don’t see: William Bendix in “The Babe Ruth Story” and John Goodman in “The Babe.”)

Ruth’s daughter laments that nobody has gotten it right.

“Comical, not real,” Ruth Stevens said of the portrayals of Ruth. “The things they had John Goodman doing, it was stupid, silly. They never got anybody who was really good.”

Where is the Ruthian film equivalent to “The Pride of the Yankees,” the 1942 film about Babe’s teammate, Lou Gehrig?

“For Lou Gehrig, they had Gary Cooper,” she said. “How much better could you do than Gary Cooper to play Lou Gehrig?”

The pursuit of Ruth has been a slippery, elusive chase of half-truths and distortions.

There is the famous story of Ruth delivering, in 1926, on a World Series promise to hit a home run for a hospital-ridden boy, Johnny Sylvester.

While the details were sometimes comically embellished, Ruth did deliver that home run on Oct. 6. In fact, Ruth hit three.

Ruth’s daughter Julia adds an emotional and telling addendum to the story.

“When Daddy was so ill with cancer, John Sylvester came to see him,” Ruth Stevens said. “He said, ‘I wish I could do for you what you did for me.’”

Ruth’s legacy endures even though most of his records have been eclipsed. Roger Maris broke his single-season home run record with 61 in 1961, and Henry Aaron and Barry Bonds surpassed Ruth’s once-thought-to-be-unassailable career home run mark of 714.

His all-time best slugging percentage of .690 is hugely impressive but mostly resonates with statistical geeks who troll Nate Silver.

Ruth endures because, as a package, on and off the field, no one approaches his staying-power swath.

He was not just a great pitcher, or just a great hitter: Ruth was both. No one in major league history has approached his dual mastery.

Ruth led the American League in earned-run average in 1916 (1.75) and, in 1924, led the AL in batting (.378).

“Who in the world has ever done that?” asked Tom Stevens, Ruth’s grandson.

In his 20-win seasons of 1916 and 1917, Ruth was a better pitcher than Hall of Famer Walter Johnson. Ruth defeated Johnson six times in eight meetings, three times by 1-0 scores.

Had Ruth stayed on the mound, he likely would have been a Hall of Fame pitcher. In 163 games, mostly amassed in his first six seasons in Boston, Ruth had a 94-46 record (including a combined 47-25 in 1916 and ‘17) and a career ERA of 2.28. He had 107 complete games.

His nine shutouts in 1916 stood as the AL record for lefties until the Yankees’ Ron Guidry matched it in 1978.

Ruth once pitched 29 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play.

Had he just been a position player, Ruth’s already incredible numbers would have been more extraordinary.

Consider: Ruth did not become an everyday player in Boston until his fourth full season. The beast was unleashed May 6, 1918, at the Polo Grounds, against the Yankees. Ruth batted sixth and went two for four, with a home run.

In 1919, his last year with Boston, Ruth batted .322 and led the AL with 103 runs, 29 home runs and 113 runs batted in. He also went 9-5 on the mound with a 2.97 ERA.

In 15 years with the Yankees, 1920-34, Ruth led the AL in home runs 10 times and in runs seven times.

Ruth hit 54 home runs in 1920, more than the total of 14 of the 15 other major league teams. His 1921 season — a .378 average, 59 home runs, 168 RBIs, 177 runs — is considered by many the greatest in baseball history.

Ruth endures because his exploits commanded boldfaced headlines in a frenetic city with 15 daily newspapers.

The intestinal ailment that plagued Ruth in 1925 — some speculated it was from eating too many hot dogs — became “The Bellyache Heard Round the World.”

Ruth’s response to making more money than President Herbert Hoover: “I had a better year.”

Ruth became such a part of our lexicon that Japanese soldiers, during World War II, would scream “To hell with Babe Ruth!” at American troops.

Ruth was foul-mouthed and a legendary carouser, drinker and womanizer. He had a hair-trigger temper. In 1917, upset over a call while pitching for Boston, Ruth walked off the mound and punched home plate umpire Brick Owens in the head.

But Ruth also had a gentle, tender side. His daughter remembers watching her father sign autographs for hours after games.

“Finally my mother [Claire] would come over and say, ‘Babe, we have company coming over for dinner, we have to go,’” Ruth Stevens recalled. “And he’d say to the kids, ‘Come back tomorrow.’”

ESPN, perhaps suffering from modern media myopia, named basketball legend Michael Jordan as the top athlete of the 20th Century. Ruth was second.

“Will we still be talking about Jordan in 100 years?” said Ed Sherman, former Chicago Tribune sports writer and author of “Babe Ruth’s Called Shot.” “Maybe, but I doubt it.”

Ruth’s aura was such that books have been written about things he might not have even done.

Dan Shaughnessy’s “The Curse of the Bambino” set out to prove Boston’s infamous 1919 sale of Ruth to the Yankees literally jinxed the Red Sox franchise. The author noted the rearranged letters of Red Sox pitcher Bruce Hurst spelled out B. Ruth Curse.

Sherman, in his book, provided 240 entertaining pages of pure conjecture. He combed through forensic and anecdotal evidence from Game 3 of the 1932 World Series to determine whether Ruth called his home run shot off Chicago Cubs pitcher Charlie Root.

We know the score was tied 4-4 and the count was 2-2. We know Ruth had been in a verbal war with the Cubs’ bench during the entire series.

Ruth made hand gestures after the first two strikes, seeming to indicate it took only one pitch to hit. We know the pitch Ruth hit was a “Ruthian” rocket, to right-center, and that he taunted the Cubs as he ran around the bases.

“It was the most unique at-bat in baseball history,” Sherman said.

The home run turned the series on a pivot toward the Yankees, but did Ruth really call his shot?

Root went to his grave swearing the whole thing was fantasy. Had Ruth been pointing, Root said, he would have knocked Babe on his rump.

The truth: it didn’t matter.

“You can argue about whether he called his shot,” Sherman said. “But he was definitely being taunted and was being challenged. And how did he respond? He delivered.”

Ruth basically “winked” about the home run and let the sportswriters run with the story.

Everything Ruth did was circus-like and over the Big Top. He carried the biggest bat, 40 ounces, in the biggest town.

Teams loaded extra defenders on the right side of the infield in a feeble attempt to foil the prodigious pull hitter. Ruth, who batted .342 for his career, said it could have been .600 if he only wanted to slap singles through the open left side.

That, he said, was not what people paid to see.

Ruth endures because enough truth exists between the lies.

Posterity’s shame is that his real life was far more exciting than Hollywood’s clown-show depictions.

Yankees teammate Waite Hoyt gave up telling Ruth stories “because nobody would believe” him.

Ruth still intrigues because, as big as he smiled, his life had a subtext of sadness born of poverty and abandonment. Ruth was not an orphan but was treated like one when his parents shipped young George to St. Mary’s Industrial School For Boys.

Ruth was dismissed as incorrigible. At 6, he was already chewing tobacco and chugging beer while snooping around his father’s Baltimore saloon.

Ruth’s daughter said her dad’s deprivation was the reason he had such an affinity for children. He related to castoffs and misfits.

“Yes,” she said, “because he certainly didn’t have much of a childhood.”

Ruth was bitter to the end about never getting the chance to manage in the big leagues.

“It was the biggest disappointment of his life,” Ruth Stevens said.

Babe’s reputation contaminated him. A front office man for the Yankees famously said of Ruth, “How can he manage other men when he can’t manage himself?”

It didn’t matter that Ruth had settled down some in 1929 after marrying his second wife, Claire, Julia Ruth Stevens’ mother.

“My mother was a very strong influence on him,” Ruth Stevens said. “I think she polished him up a bit. Col. [Jacob] Ruppert [the Yankees’ owner] asked her to go on the road with him to keep him on the straight and narrow.”

Ruth Stevens said her father played golf almost daily after he retired to keep from sinking into deep depression.

“He’d come home and ask Mother, ‘Did anyone call?’ meaning anyone interested in him becoming a manager,” she recalled.

No one called.

Ruth Stevens speculates baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis blackballed her father because the commissioner was a bigot who feared Ruth might integrate the major leagues with black players.

“And he would have,” Ruth Stevens said. “He used to play exhibitions with Satchel Paige; he knew lots of Negro players.”

Ruth Stevens can’t reclaim history but she can close her eyes and play back the magic moments. “I loved to see him take his cap off and wave to the crowd as he ran around the bases,” she said.

She remembers not the history-reel shots of an aging, bloated Ruth, but a real man with human flaws and uncommon physical grace. Who might recall that Babe Ruth stole home 10 times?

“He was a beautiful dancer,” she said. “He taught me how to dance. The Foxtrot.”

Talking about that day in 1948 when Grantland Rice wrote, “Game called by darkness. Let the curtain fall . . . where is the crash of ash against the sphere?” still doesn’t come easily to her.

One hundred years after his first game, more than six decades after he left us, Babe Ruth is surely not forgotten.

“I miss him even to this day,” his daughter said. “I miss him so much. But his spirit seems to hover over the baseball field.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.