Commentary: Dodger Stadium renovations are latest masterpiece designed by Janet Marie Smith

On Aug. 6, 2012, three months into the tenure of the Dodgers’ new owners, the team made three transactions. The Dodgers cut outfielder Tony Gwynn Jr., called up outfielder Jerry Sands and signed executive Janet Marie Smith.

Gwynn never again played a full season in the major leagues. Sands never did. Smith is still here, and her latest masterpiece for the Dodgers is only the most recent example of why she should be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Smith is America’s foremost ballpark designer. She first made her name in Baltimore, where Larry Lucchino, then president of the Orioles, envisioned an intimate neighborhood ballpark.

“This was at the same time the Blue Jays were building the eighth wonder of the world,” Lucchino said in an interview.

The Toronto stadium known as Skydome opened to grand fanfare in 1989, with a retractable roof that inspired awe. The Blue Jays touted their new home as “The World’s Greatest Entertainment Centre.” They got the downtown location right, but the vast multipurpose concept all wrong, and now they want out.

Smith designed Camden Yards, which integrated a crumbling warehouse into its setting. Lucchino recalled a Baltimore columnist deriding the warehouse as “an empty, rat-infested fire trap,” but it emerged as the signature design element, so beloved it inspired the San Diego Padres to incorporate the old Western Metal Supply Co. building into Petco Park.

Camden Yards opened in 1992, and suddenly every team wanted one just like it: not a copy of it, but a baseball-only facility with its own features and quirks.

“Ballparks in baseball are different than arenas in other sports,” Lucchino said. “They each have a distinctive personality.”

When the Atlanta Braves were handed that city’s Olympic stadium in 1996, Smith got the assignment of downsizing it into a ballpark. When the Boston Red Sox looked to renovate Fenway Park for a second century of use, Smith got that assignment too, incorporating office buildings, laundry facilities and even airspace above an adjacent street to expand a ballpark wedged into a city block.

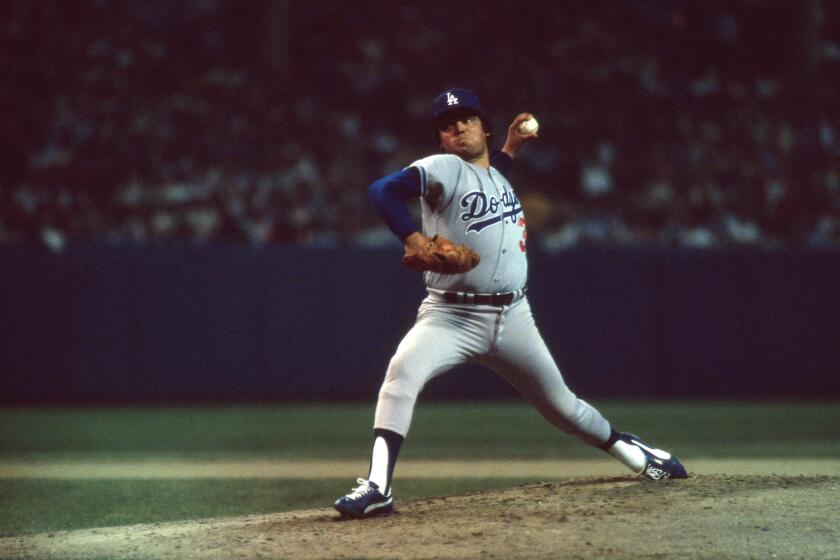

Fernando Valenzuela became a star pitcher with the Dodgers in 1981, igniting Fernandomania and giving Mexican Americans a hero still revered today.

“Janet’s middle name,” Lucchino said, “is preservation.”

That made her the perfect choice for the Dodgers’ new owners. The renovation the Dodgers unveiled Wednesday is her second major project for the team, and one that will make Dodgers fans smile — and exhale.

The concept of adding a Dodger Stadium entrance plaza in center field is not new. Our old friend Frank McCourt pitched the idea before he ran out of money: Fifteen acres of restaurants and shops and a Dodgers museum, with team offices and parking structures.

Smith’s version covers two and a half acres. It honors the sense of place.

Dodger Stadium is our oasis on a hill, an escape from the everyday world. We do not need Dodger Stadium to be a mall, or an entertainment center, or an urban village.

“Too much is too much,” Smith said. “You still want an intimacy. We’re still here to watch the game and celebrate the Dodgers.

“We weren’t looking to create a theme park. We were looking to create the kind of amenities that other ballparks have, but in a way that respected the original architecture of Dodger Stadium.”

Dodger Stadium is opening up to fans for the first time in two years. Here’s how to attend a game with new protocols due to the coronavirus pandemic.

There are concession stands and picnic tables, not sit-down restaurants. There is an Airstream trailer turned into a baseball cap stand, a vintage ice cream truck, and a Dodger blue fire truck with taps for lemonade and beer.

Smith amplified the stadium’s mid-century style, rather than obscuring it in the name of modernization. The rainbow colors in the club level seating area are back, signs are shaped in the classic hexagons of the Dodger Stadium scoreboards, and a Tommy Lasorda-inspired lounge evokes the decades before disco. Smith playfully used beach balls in a lighting motif, and she even planted two orange Union 76 balls on the grounds, as nostalgic surprises for fans that remember the old gas station in the stadium parking lot.

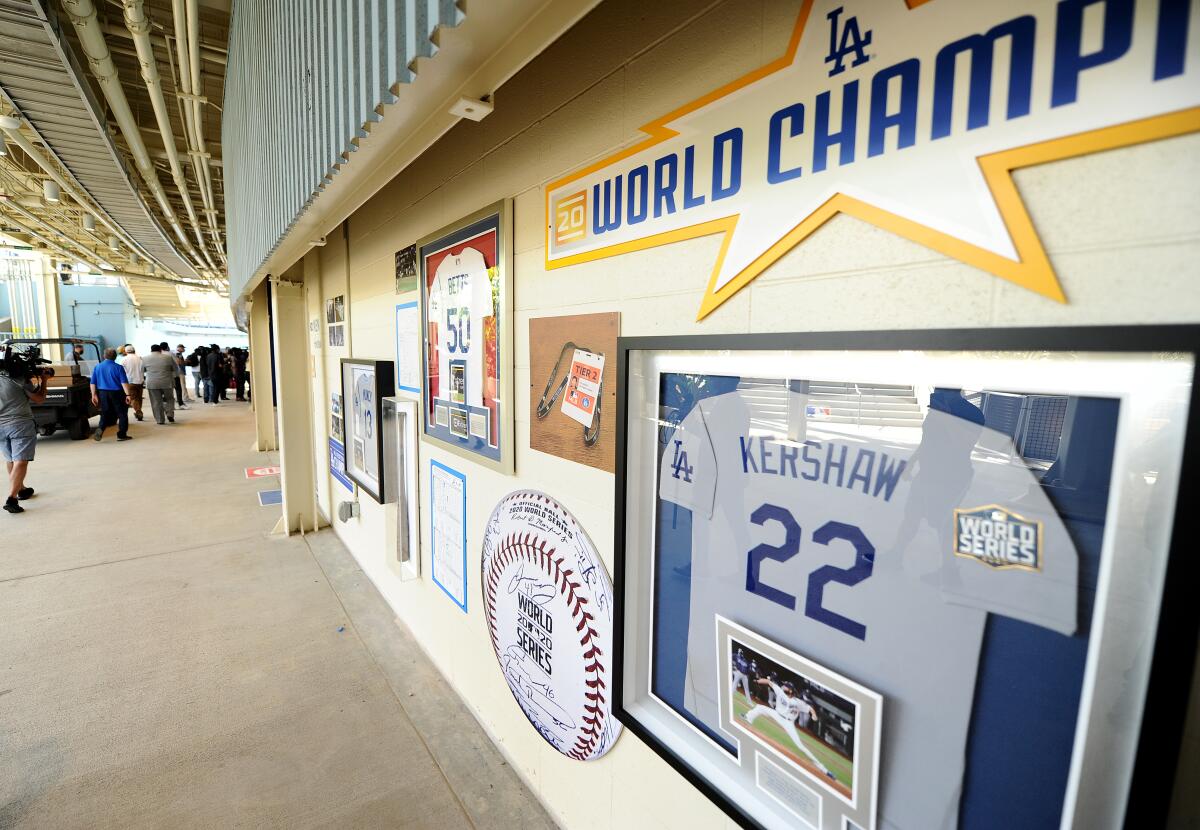

No sport binds the generations like baseball does. Instead of assembling artifacts in a building, the Dodgers leveraged their latest renovation to create what team President Stan Kasten called an “open-air baseball history museum.”

Kids can use play areas, stand behind center field and watch the Dodgers take batting practice, step into a cage for some batting practice of their own, and pose with a virtual image of their favorite player for a picture. Along the way, parents can share team history as they pass the Jackie Robinson statue, displays honoring Lasorda and Fernando Valenzuela, street signs from the Dodgers’ old spring home in Vero Beach, Fla., and broadcaster Joe Buck’s scorecards from the 2020 World Series.

In Baltimore, Smith reinvented ballpark architecture for the modern era. In Boston, and again in Los Angeles, her preservations and enhancements saved two of baseball’s storied franchises from having to make a painful choice: stay in a revered but cramped ballpark, or move to a new one with contemporary amenities?

Architects so far inducted into the Hall of Fame are team architects, not ballpark architects. To Lucchino, and to Kasten, Smith deserves a call to the Hall.

“She’s got mad skills,” Kasten said. “Her body of work is extraordinary. More people are noticing it, and I’m sure the Hall of Fame will too.”

Ballplayers come and go, but few have the lasting impact of Smith. When Cooperstown recognizes the decade in which a proud but bankrupt franchise was restored to glory, the inductees should be Clayton Kershaw and Janet Marie Smith.

A look at the new changes awaiting fans returning to Dodger Stadium on Friday.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.