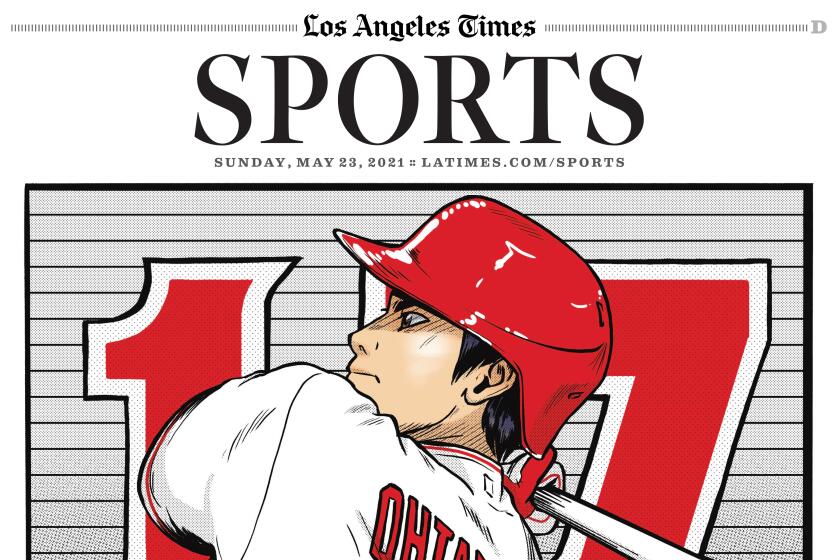

Best comparisons to Shohei Ohtani’s two-way exploits came in the Negro Leagues

Although Joe Maddon has seen every home run Shohei Ohtani has hit and every pitch he has thrown this season, the Angels’ manager still has trouble putting the historic performance in perspective.

“We have to go back to [Babe] Ruth to draw any comparisons,” Maddon said last week. “There’s not been one name mentioned, other than his, to compare Shohei to. We all romanticize what it would have been like to watch Babe Ruth play. He pitched, really?

“You hear this stuff, and it’s a larger-than-life thought or concept. Now we’re living it.”

Bob Kendrick nodded knowingly when he heard those comments.

A former promotions-department copywriter and college basketball player, Kendrick is president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo. It’s a role he has used to teach the United States about a forgotten chapter in its history while raising the ghosts of yesterday, giving them the due in death they never received in life.

The Negro Leagues had their heyday between World Wars I and II, the same time Ruth was rewriting the record book. And that, Kendrick knows, cast a large shadow that obscures our view even now.

“I don’t take it personally when they just speak of Ruth because Ruth is the name they know,” he said. “They’ve always heard about Babe Ruth.

“As my late mother would say, you don’t know what you don’t know.”

However, the best comparison for Ohtani’s incomparable season isn’t Ruth, he continued. It’s “Bullet Joe” Rogan, Martín Dihigo, Leon Day and Ted Radcliffe, men whose exploits are not well known because they were banned from the white major leagues because of their skin color.

Baseball’s decision last winter to recognize the Negro Leagues as true major leagues finally opened the way for the performances of 3,448 players — 34 of them Hall of Famers — to be integrated with statistics from the six segregated leagues, allowing an apples-to-apples comparison between what Ohtani is doing now and what has been done before.

“The success of Ohtani has given us an opportunity to tout the great two-way stars of the Negro Leagues,” Kendrick said. “I’m so excited and proud of what he’s doing because it has given us really a platform to celebrate those Negro League players who were doing this routinely.

“This is an opportunity to help remind people. And maybe they’ll want to learn more about these legendary players.”

Let’s be clear we’re talking about comparisons and not arguing over who did it better. Because nobody has come close to doing what Ohtani has done this season.

He will go into the Home Run Derby on Monday leading the majors with 33 home runs, five of which have traveled more than 450 feet. In the mile-high air of Denver, air traffic control might be needed to track his blasts.

On the mound, he’s 4-1 with a 3.49 earned-run average in 13 starts, good enough to become the first man selected to the All-Star game as both a pitcher and a position player. He will hit and pitch in Tuesday’s game, American League manager Kevin Cash said.

Although Ruth was twice a 20-game winner on the mound and once was the single-season and career home run leader at the plate, he never really hit and pitched full-time in the same season as Ohtani is doing. Only once did Ruth have more than 320 at-bats and pitch more than 130 innings in the same season, numbers the Angels star is on pace to match this year.

“Ohtani would have fit in great in the Negro Leagues. He has the skill set they were looking for,” said Scott Simkus, a former Chicago limousine driver who spent much of the last two decades working with other researchers to build the statistical database of the Negro Leagues now available online at SeamHeads.com.

Negro League rosters were often just 15 or 16 players deep. And with teams frequently playing multiple games on the same day, versatility was a must. As a result, a team’s best hitter was often one of its top pitchers as well.

“It was born out of necessity,” Simkus said. “These guys were actually part of the rotation. And in some cases, the best pitchers on the team.”

Radcliffe’s nickname, Double Duty, spelled out his value. It was given to him by sportswriter Damon Runyon, who watched Radcliffe catch a Satchel Paige shutout in the first game of a 1932 doubleheader, then throw one of his own in the nightcap.

That wasn’t the only time he worked both sides of the plate: In six East-West All-Star Games, Radcliffe pitched in three and caught in three.

Dihigo, who made his Negro League debut at 17, played at least 235 innings at eight different positions during a career that earned him enshrinement in five different halls of fame — in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Venezuela, his native Cuba as well as Cooperstown. In 12 Negro League seasons, he hit .311 while winning 30 games on the mound, according to SeamHeads.

Day, a right-hander, made his debut in the Negro National League at 17 and went on to make 80 starts, winning 51 times. But he also batted .309 in 10 seasons, spent mostly with the Newark Eagles. Even “Cool Papa” Bell, a switch-hitting outfielder who batted .325 and stole a record 300 bases in 21 seasons, started his career as a left-handed knuckleball pitcher, throwing 153 2/3 innings in his second season.

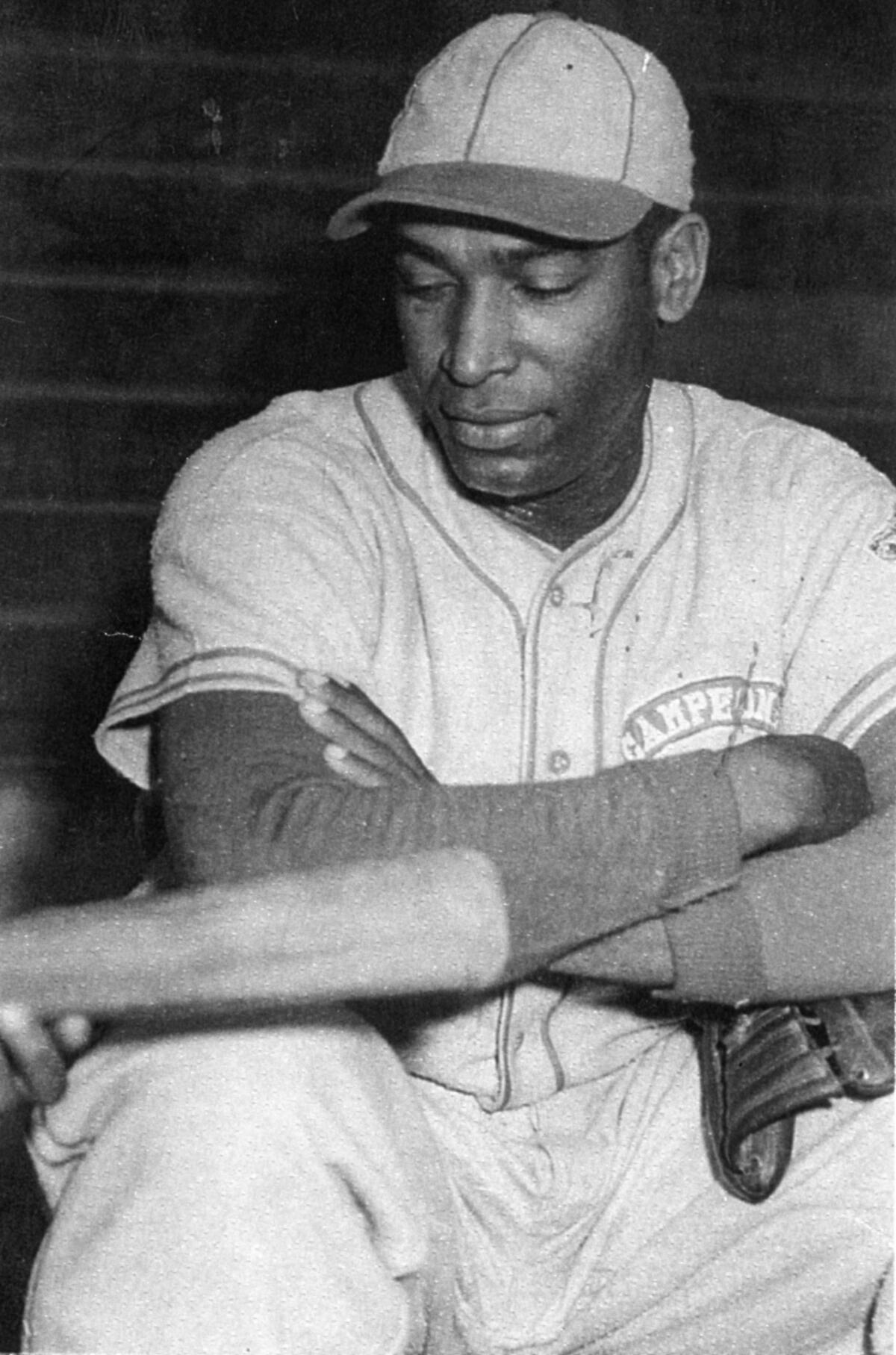

But Rogan, an Army veteran who didn’t join the Negro Leagues until he was 27, offers perhaps the closest comparison to Ohtani, also 27. Although he stood just 5 feet 7 and weighed 160 pounds, Rogan, a right-hander like Ohtani, had a blazing fastball — hence the nickname “Bullet.” And like Ohtani, Rogan established himself first as an everyday player before making a career-high 25 starts in his third season.

He wound up second in Negro Leagues history with 130 wins, while at the plate he hit .336 in 17 seasons, playing every position except catcher. His best two-year stretch came from 1924 to 1925 when he hit .380 while going 36-8 with 38 complete games and a 2.51 ERA.

Ohtani won’t touch those numbers.

Two years later, Rogan added manager to his resume, finishing first five times in 11 seasons while continuing to pitch and roam the outfield. And when he could no longer play, he became a Negro Leagues umpire.

“Rogan was probably the best two-way player in the Negro Leagues just because of the length of his career,” Simkus said.

Want more proof? According to the website FiveThirtyEight.com, just two players since 1901 have produced a WAR (wins above replacement) of at least four per 162 team games as both a pitcher and a batter in the same season. Rogan did it four times.

“Because of the short rosters the Negro League teams had, everybody had to be good at everything. Which oddly was pretty much like white baseball in the 1850s and ‘60s,” said John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian. “But remember that Ohtani is on a 26-man roster. And he’s throwing 100 miles an hour. And he’s hitting 33 home runs.

“So these things are indeed without precedent.”

Ohtani’s success, combined with the current trend of packing rosters with 13 or 14 pitchers, is leading some teams to rethink the concept of two-way players. Thorn says he wouldn’t be surprised to see a return of versatile players in the mold of the old Negro Leaguers.

“It’s very good for baseball,” he said. Acclaimed author “Larry Ritter liked to say the best thing about baseball today is its yesterdays. And whenever somebody does something spectacular on the field, everybody goes scurrying to the record books and the ghosts come alive again.”

Ghosts such as Rogan, Day, Radcliffe and Dihigo, who have been stirred — and newly appreciated — thanks to Ohtani.

Shohei Ohtani’s two-way exploits will be among the highlights during the All-Star game and home run derby. Check out The Times’ complete coverage.

“The statistics are fans’ shorthand stenography for our stories,” Thorn said. “And if the stats don’t lead to stories, then they just hang in the ether not having any real meaning.”

Times staff writer Jack Harris contributed to this story.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.