Angels’ Matt Shoemaker feels good as he comes back from line drive to the head and brain surgery

- Share via

Reporting from Rockwood, Mich. — Matt Shoemaker and his wife were raised near Detroit and they do not intend to move from the area any time soon, but spending baseball off-seasons in the cold presents problems.

Most weekdays, the Angels right-hander makes the 35-minute drive from his suburban home to the campus of either Wayne State or Eastern Michigan, his alma mater.

Both universities have large indoor athletic facilities, where he can throw alongside the college teams, which are happy to host a major leaguer — in this case, one mounting a comeback.

“We try to go outside when it’s 40 or above,” Shoemaker said.

So, on a recent afternoon, Shoemaker parked his Ford Escape in an alley, grabbed his glove from the passenger seat, and headed inside to greet Wayne State Coach Ryan Kelley.

The temperature had climbed, melting ice left over from a weekend snowstorm and reaching a mid-afternoon high of 42.

“Outside?” Shoemaker asked, and the coach nodded.

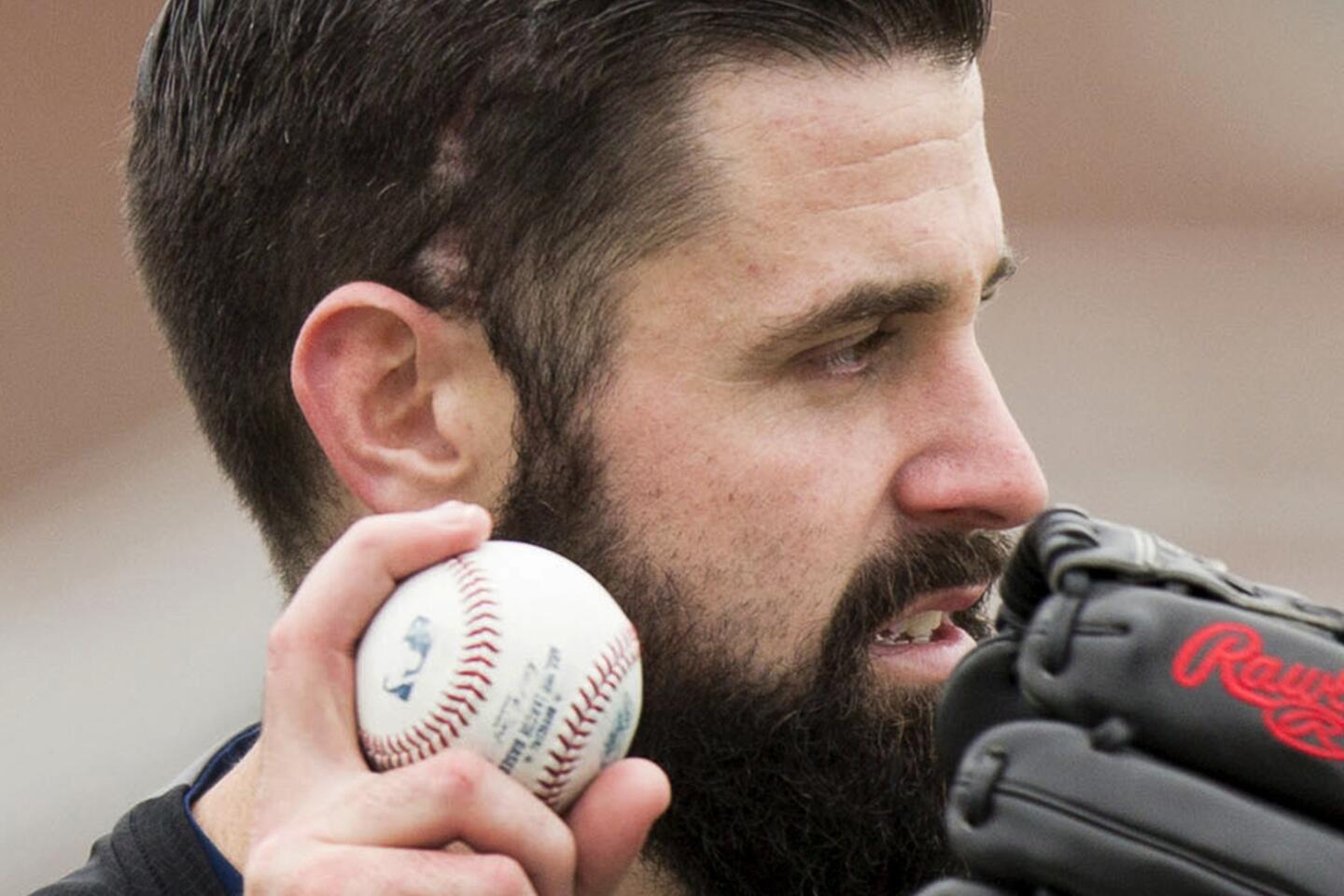

Wearing a workout shirt, shorts and leg sleeves, Shoemaker completed his 20-minute throwing progression on the football field’s periphery. Everything, even the leaps he took in pursuit of errant throws, looked normal. Except for one thing.

The steep scar stretching from his right ear to the top of his head was emphasized because he was not wearing a hat.

::

Shoemaker’s mother, Karen, was watching on television from her sister’s home in Northern Michigan, where the family had gathered over Labor Day weekend.

His wife, Danielle, eight months pregnant and on bed rest, was watching from their rented home in Anaheim.

It was Sept, 4, 2016. Shoemaker struck out the first two Mariners he faced that afternoon in Seattle, and his family anticipated another strong outing for him in a season full of them.

Until the second inning, when Mariners All-Star Kyle Seager hit a line drive that struck Shoemaker in the temple and sent him crumpling to his knees.

As an Angels trainer rushed to the mound and draped the bloody wound in a towel, Karen began to cry.

Danielle fixed her eyes on the screen, seeking signs of normalcy from the man with whom she had built a life. Her husband was on his feet, moving ably yet carefully, before he was taken off the field and out of sight, to the clubhouse. Soon her phone buzzed.

Caller ID told her a club executive was calling, but the voice on the other end belonged to Albert Pujols, the Angels’ designated hitter that day. He assured her, then passed the phone to Matt.

“He sounded more mad than anything,” Danielle recalled.

Later, after undergoing two brain scans at the Harborview Medical Center, Matt called to say he was OK. His head hurt but he had never lost consciousness. He reasoned that he might miss a start or two. One more scan would be performed later, he said, just for confirmation.

Danielle ate dinner with her visiting parents and felt a bit better before she received a FaceTime request from her husband just before 9 p.m.

“They’re wheeling me into surgery right now,” he said, jolting her. “You’ll get a call explaining it. Can you tell my parents?”

I can’t say with 100% certainty that it’s not going to affect me on the mound, but I feel 100% sure.

— Matt Shoemaker, on facing a batter for the first time after getting hit in the head with a line drive last season

Danielle called the couple’s then-19-month-old son, Brady, over to the phone.

“In my head, I’m like, ‘Is this the last time I’m ever gonna talk to him? Is this the last time Brady’s ever gonna talk to him?” she remembered. “Up until then, I thought, ‘It’s bad, but it’s gonna be OK.’ Then, all the sudden, it was super extreme.”

Said Shoemaker: “Not once did a worry come over me, like, ‘Oh, gosh, am I gonna be OK?’ Until we went into surgery. And then it was all real.”

::

The ball came off the bat at 105 mph and its impact induced bleeding inside Shoemaker’s brain, which had not subsided. A two-hour surgery was required to save his life.

Back in Michigan, the pitcher’s father, David, remained awake until the early morning hours, awaiting an update.

“My heart went as fast as it’s ever beat in my life,” he recently recalled. “Flashes are going through my head, like ‘What if?’ I started thinking about Danielle. Here we were, 2,500 miles away. You talk about your most helpless point as a parent.”

Using his phone’s MLB app, David searched for video of similar incidents. By then, he had already seen the replay of Matt being struck many times, on MLB Network and ESPN. Now he watched line drives strike the heads of other pitchers and studied the subsequent seconds.

“I’m not trying to be morbid,” he said. “I just wanted to see what their response was when they got hit.”

At least a dozen major and minor league pitchers have been similarly struck in recent seasons. One of them, triple-A pitcher Evan Marshall, saw what happened to Shoemaker and compared it to his own experience while pitching in a triple-A game in 2015.

“It was about as similar as what happened to me as is possible,” he said during a phone interview last month. “And it’s about as bad as anything can possibly be on a baseball field without dying.”

Marshall didn’t pitch to a hitter until five months later, during spring training. He appeared in 15 games for the Arizona Diamondbacks last season and will compete for a spot on the club’s 25-man roster this spring.

“I really didn’t run into any speed bumps in the rehab process, other than just coming to the reality of how bad my condition was,” Marshall said. “The psychological aspect of getting back onto the mound, something that traumatic, it left me with nightmares and re-living over and over again that still to this day happen.”

::

No one knows what trials Shoemaker, 30, may confront the next time he faces a batter. But the obstacles he already has overcome are unmistakable.

Of the 1,504 ballplayers picked in the 2008 MLB draft, none of them were him.

He careened on an ice patch and suffered a fractured left arm before his final season at Eastern Michigan. He rushed back, and scouts who saw him early removed him from draft consideration.

The Angels signed him as a free agent for $10,000 because they needed an arm in the low minors to finish out the year.

Over his first three professional seasons, Shoemaker was a steady performer but earned no notice. During off-seasons, he paid the rent on the starter apartment he and Danielle shared by working as a substitute teacher.

The school district would call at 6 a.m. and tell him where to report. He worked between three and five days a week, kindergarten through 12th grade. Every day the phone rang, he earned $92.50 in pre-tax wages.

“Some days were great,” he said. “But so many days were bad that it trumps them.”

Every day of the 2017 season, Shoemaker will make 200 times his substitute salary — $18,472.22. He has a $3.325-million contract and stands to multiply that in years to come if he can regain his form.

He marvels at the incongruity of that figure, and the idea that he’ll make more money over a few months of doing something fun than he’s made in his life. And he finds comfort in the effort required to get here.

“With the contract and how it was weeks before that this happened, that is more ammo for my journey, for my cool story,” Shoemaker said.

“I like going out there and telling people my story: the fight, the hard work, all that stuff mixed together. Talking to people about it gives them the idea that, if it’s baseball or anything, whatever it is, just, please, work hard.”

Shoemaker didn’t stop substitute teaching until a dominant 2011 season in double A earned him an invitation to major league spring training. But his earned-run average shot up in 2012 in hitter-friendly conditions at triple-A Salt Lake, and he was back with the minor leaguers the next spring.

Pitching in Japan or South Korea became an option. He’d make more money for the family he hoped to start with Danielle, but he’d hamper his major league dream. He decided to try with the Angels once more.

Wielding a tightened splitter and with renewed focus, he struck out 160 that season and walked only 29. On Sept. 16, 2013, the Angels called him up.

The next season, Shoemaker won 16 games and finished second in voting for rookie of the year.

Manager Mike Scioscia repeatedly called Shoemaker the savior of his 98-win team and compared his in-game intensity to Nolan Ryan’s.

By September of last season, Shoemaker was an established major leaguer. Then came the hit he never saw coming, one that could have concluded his career.

“I know how easily it could have been different, and that’s why I’m so thankful to God,” Shoemaker said. “He had his hand on me that day, seriously.”

He has undergone an array of checkups, coordination quizzes and a concussion exam to compare his neurological state against an old baseline. At his first consultation, doctors sought to see what he felt when his heart rate skyrocketed, so he ran on a treadmill. He hadn’t worked out in two months.

That, he said, might have been the toughest thing he had to do all winter.

::

Four days after surgery, Shoemaker returned home to Anaheim. For five days after that, he was unable to eat and miserably sensitive to light and sound. But in time, his life resumed a familiar hue, with a few exceptions.

On the last day of the regular season, Danielle gave birth to Emmy, their second child. When Matt appeared on “Good Morning America” that week, he told reporter Kayna Whitworth about the titanium plate forever embedded within his head to secure the sutures.

Watching the show, his parents had the following conversation:

David: “Did you know that?”

Karen: “No. Did you?”

“No.”

Danielle and Matt met a dozen years ago, through church, the summer before he went to college. One year younger, her spunkiness complements his quiet conviction.

They plan to move to a larger place soon, but for the last five years they’ve kept a modest two-story home in a sleepy southern suburb of Detroit. They picked it because the street was populated by seniors and close to their parents’ houses.

During a muted moment there last month, as Emmy slept and Matt checked his phone, Danielle volunteered a thought as she prepared Brady’s dinner.

“Sometimes,” she said, “it doesn’t even feel like it really happened. I’ll be like, ‘Oh, my husband had brain surgery.’ It doesn’t seem like that really happened.”

But there are reminders. For weeks at church, congregants sought them out to say they were praying for him. Headgear, too, is a common topic of discussion, although Shoemaker has not found anything he likes and has told friends he plans to pitch without additional protection.

The family has not shied from pitching; Brady has recently revealed himself as a natural left-hander, and his grandfather is elated.

In recent years, Shoemaker had commenced and completed every season by driving to and from Michigan with the family’s American and English bulldog mix, Samson. At last season’s end, Danielle insisted he not drive alone, so his dad flew out to do it.

Feeling healthy again, Shoemaker packed his bags and his bulldog into his car this week and steered it toward Tempe, Ariz., for spring training. Eager, he completed the 30-hour trek in two days.

“I can’t say with 100% certainty that it’s not going to affect me on the mound, but I feel 100% sure,” he said of his injury. “Honestly, the only time I think about it now is when I’m asked about it or when I’m doing my hair and I see my scars.

“It might be different when I face a live hitter for the first time, but it might not be.

“I hope it won’t be.

“I don’t think it will be.”

Twitter: @pedromoura

ALSO

Angels could quietly be building a playoff contender

Angels acquire right-handed pitcher Austin Adams from Indians

Several big-name players with big-money pedigrees still available in MLB free-agent market

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.