Q&A: How to talk about politics with people who don’t agree with you

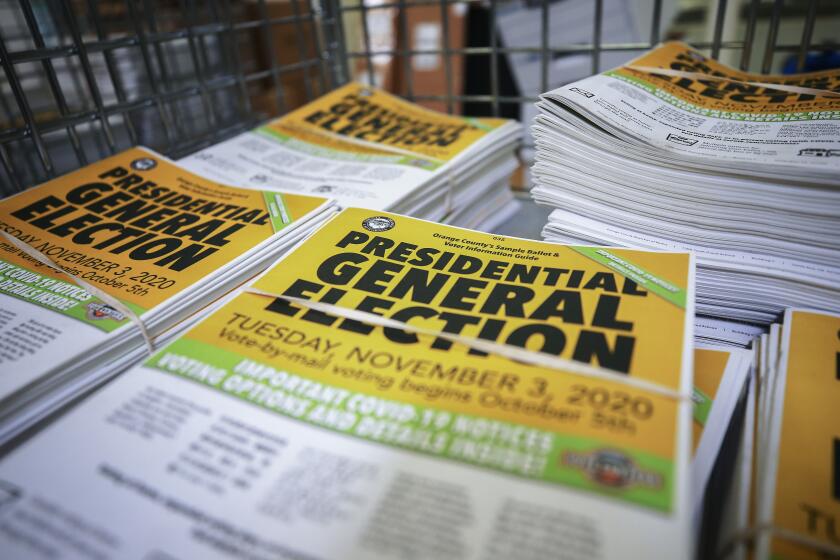

These days, there’s no surer way to start a fight than to talk politics with someone who disagrees with you. And with election day drawing near, political conversations are increasingly difficult to avoid.

You could muddle your way through the next two months and hope for the best. Or you could take Tania Israel‘s advice and embrace the opportunity to help bridge America’s political divide.

Israel, a professor in the Department of Counseling, Clinical and School Psychology at UC Santa Barbara, has been facilitating difficult conversations since the 1990s, when she brought together people on opposite sides of the abortion debate.

“It was a transformational experience for me,” Israel recalled. “It didn’t change anything about how I felt about reproductive rights, but it changed so much about how I felt about people who disagreed with me.”

In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, she stepped up her efforts to connect with people outside her bubble and wrote a book to guide others willing to do the same. “Facing the Fracture: How to Navigate the Challenges of Living in a Divided Nation,” inspires readers to listen to their fellow Americans rather than debate them.

Israel spoke to The Times about how individual conversations can help the country heal. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Why does it seem like there’s more political conflict than there used to be?

People are struggling not just with arguments with their uncle, but arguments with their phone, with the news, and in their own heads. All of that makes us very emotionally activated, which is part of the reason stress-related political conflict is on the rise and keeps going up.

It’s not healthy for us, it’s also not healthy for our relationships, and it’s not healthy for our democracy.

Scientists explain how our politics got so bad that we can’t come together to confront common threats like the national debt, climate change and COVID-19.

Is it good to try to bridge the divide, or is it better for your mental health to steer clear?

I think what’s best for people is to build the capacity to be able to do both — to be able to have those conversations, and also to be able to know when it’s best not to.

What motivates people to engage with someone from the other side?

Some people say, “I want to maintain a relationship with somebody in my life and we’re having trouble doing that because of political conflict.”

Some people say they want to persuade or convince someone else.

Some people say they want to find common ground or heal the divide.

And then some people say, “I simply cannot fathom how people can think or act or vote like they do,” and they’re looking for some insight.

Are we so used to being on our phones and that makes it hard to deal with people in real life?

It’s much easier to have stereotypes of people when we’re engaging with them only as social media accounts. It distorts our understanding of who other people are.

A new poll shows that California voters are increasingly moving to social media, such as TikTok, for election information.

Are stereotypes the only problem?

As humans, we have these cognitive biases where we see ourselves as being very rational, basing our ideas on solid information. But we see people on the other side as being irrational, illogical, and being brainwashed by misinformation. Both sides are seeing things this way.

My favorite cognitive bias is called motive attribution asymmetry, where we see ourselves as being motivated by protective, caring motives, and we see the other side as being driven by selfishness and by hostility.

How can we correct our cognitive biases?

Recognizing them is probably the most important thing.

We can recognize the other side’s biases. If we just recognize that we are susceptible to all of those same things, that can help us to have that curiosity to correct them.

If you find yourself in the middle of a polarizing argument, how can you turn things around?

The best thing we can do if we’re trying to find common ground, persuade somebody, or gain insight is to try to understand them better.

The way we do that is we listen. We encourage people to elaborate. We manage our own emotions. And when we do share with people, we share stories instead of statistics and slogans.

Stories are processed in the brain differently from other types of information and can profoundly affect people’s beliefs and behaviors.

That’s not what people think they’re supposed to be doing. They think they’re supposed to be having a debate, where they’re bringing in all the information and the stats and the rationale.

Why are stories better than statistics?

When we’re using stats and arguments, we’re drawing those from our trusted sources, which are very often not the same as the trusted sources of the person that we‘re talking to.

Confirmation bias causes us to accept information that supports what we already believe to be true, and ignore or dismiss information that conflicts with our beliefs. So when we’re telling people things that are in conflict with what they believe, they are more likely to dismiss what we’re saying — and frankly, to dismiss us as a trusted source.

When we embed information in stories, people remember it better and they accept it more. It’s also how humans relate to each other. Not only is it more effective, it’s a more interesting conversation.

Scientists will say an anecdote is not data. But you’re saying an anecdote is better than data.

Right. We can have all of the information, but when we’ve got another human being involved, it turns out that just telling them all the information doesn’t help.

If we believe in science, we also need to believe in the science that says that’s not the way you get someone to change their behavior.

Why would someone who doesn’t trust your facts trust your story?

Stories feel more true. And you can’t argue with stories, you know? “Here’s my story of my life.” You can’t argue with my story of my life. Also, if there’s some emotion in the story, people connect with that.

We often put our ideas out there to say, “Here are my ideas. This is why you should believe it.” Or to say, “Here are my ideas. This is why this justifies what I think or do.” We very rarely put our ideas out there to say, “Here are my ideas. Here are the limits of my understanding of this. What am I missing?”

That is a completely disarming approach because it brings intellectual humility into it. We can have very strong beliefs but still have curiosity about and respect for views that might be different from our own. That’s going to help to broaden our understanding.

Is one side of the political spectrum really losing ground with the public, and if so, on what issues?

It seems like you’d have to be in the right mindset to want to talk with someone you’re used to disagreeing with, no?

We have to work up the capacity to do this. There are habits we need to form and habits we need to reform. All of that training is going to help us be able to face political division, as well as other challenges in our lives.

What’s involved with that training?

The first step is to reduce polarizing input. We can consume news more wisely, use social media more intentionally and correct our cognitive biases. That’s going to help us be in a space of equilibrium.

Next is building our individual capacity through emotional resilience. That’s being able to face a person or a lawn sign and not completely melt down.

Intellectual humility helps us broaden our minds, and you’re absolutely right that you have to want to do that. It’s about having the curiosity to recognize that you might not have the full story and that there’s something more you can learn.

And then there’s compassion. You’ve got to take all these steps before you can even get to building empathy and compassion.

Once you’ve done all of that, now you’re ready to strengthen connections.

How?

If you want to engage across the divide, you want to do so effectively — listening to others, telling stories, all of that.

It’s also engaging with our communities and our country. Civic engagement is a really important activity. Do something meaningful to support the causes that you care about. Volunteering not only benefits us as society, it also benefits our mental health.

Posting something on social media is not a very effective form of advocacy. Turning away from our screens and engaging with other three-dimensional human beings is probably the best thing we can do for any of these issues.

Political pundits have called America a ‘polarized’ country. But it was never true — we agree on most issues.

There’s also this thing most people have never heard of, which is the bridging movement.

What’s that?

There are over 500 organizations that are working on bridging divides and strengthening our democracy. If people join that movement, it’s great. But just knowing that that’s happening can make people more optimistic about their fellow Americans, and about the future of our country.