California scientist, two others win Nobel for ‘totally crazy’ work on quantum physics

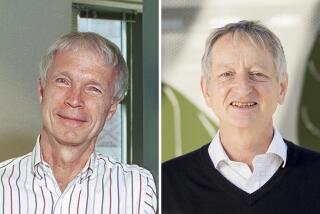

STOCKHOLM — A Northern California scientist and two European researchers won the Nobel Prize in physics Tuesday for proving that tiny particles could retain a connection with each other even when separated, a phenomenon once doubted but now being explored for potential real-world applications such as encrypting information.

American John F. Clauser, Frenchman Alain Aspect and Austrian Anton Zeilinger were cited by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for experiments proving the “totally crazy” field of quantum entanglements to be all too real. They demonstrated that unseen particles, such as photons, can be linked — or “entangled” — with each other even when they are separated by large distances.

Quantum entanglement “has to do with taking these two photons and then measuring one over here and knowing immediately something about the other one over here,” said David Haviland, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics. “This allows us to do things like secret communication, in ways which weren’t possible to do before.”

It all goes back to a feature of the universe that baffled Albert Einstein.

Bits of information or matter that used to be next to each other but then become separated have a connection or relationship — something that can conceivably help encrypt information or teleport it from one place to another.

A Chinese satellite used these principles to create a quantum channel between the ground and space. Potentially lightning-fast quantum computers, still at the not-quite-useful stage, also rely on this entanglement. Others are even hoping to use it in superconducting material.

“It’s so weird,” Aspect said of entanglement in a call with the Nobel committee. “I am accepting in my mental images something which is totally crazy.”

Yet the trio’s experiments showed it happens in real life.

“Why this happens I haven’t the foggiest,” Clauser said during a Zoom interview from his home in Walnut Creek. “I have no understanding of how it works, but entanglement appears to be very real.”

His fellow laureates also said they can’t explain the how and why behind this effect. But each performed ever-more-intricate tests that prove it just is.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

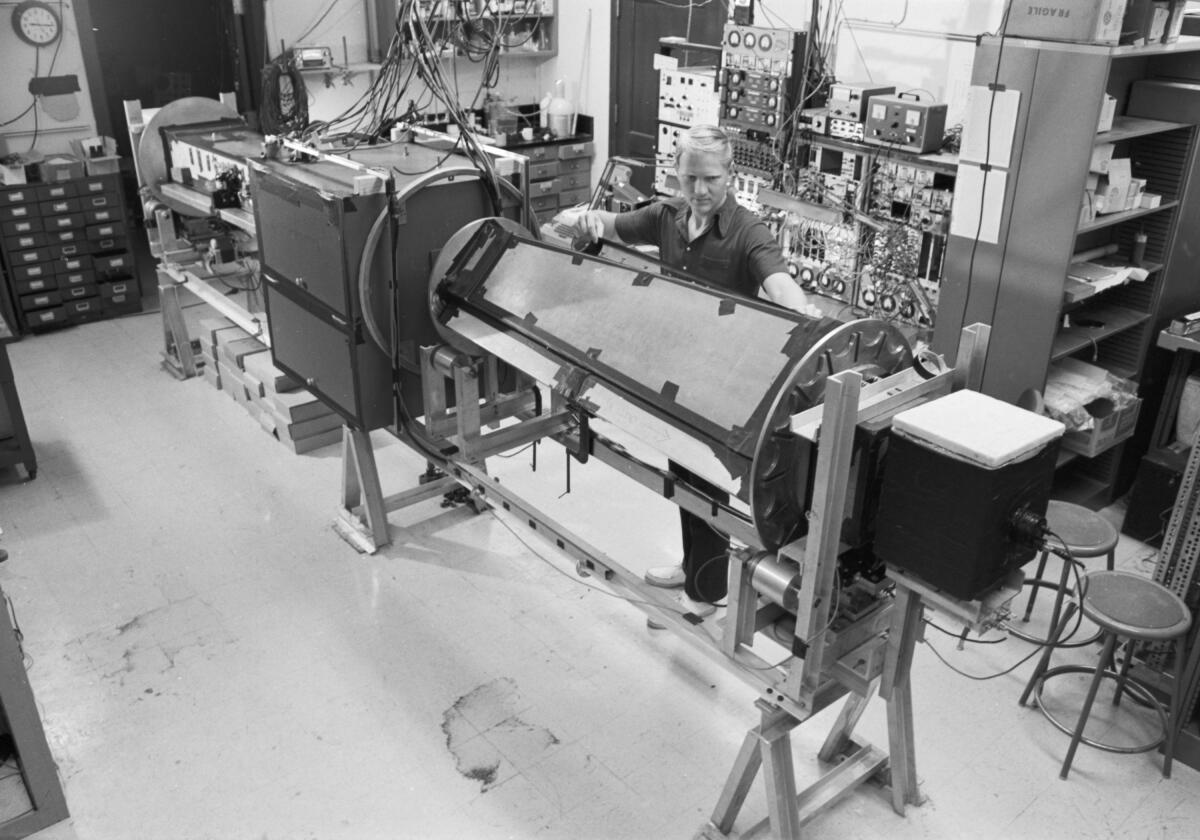

Clauser, 79, was awarded his share of the prize for a 1972 experiment, cobbled together with scavenged equipment, that helped settle a famous debate about quantum mechanics between Einstein and famed physicist Niels Bohr. Einstein described “a spooky action at a distance” that he thought would eventually be disproved.

“I was betting on Einstein,” said Clauser, who built a video game on a vacuum tube computer as a high school student in the 1950s. “But unfortunately, I was wrong and Einstein was wrong, and Bohr was right.”

Aspect said Einstein may have been technically wrong, but he deserves huge credit for raising the right question that led to experiments proving quantum entanglement.

This mind-boggling field began with thought experiments that bordered on philosophical musings about the universe.

“With my first experiments I was sometimes asked by the press what they were good for,” Zeilinger, 77, told reporters in Vienna. “And I said with pride: ‘It’s good for nothing. I’m doing this purely out of curiosity.’”

It’s good for something now. The kind of secure communication used by China’s Micius satellite — as well as by some banks — is a “success story of quantum entanglement,” said Harun Siljak of Trinity College Dublin. By using one entangled particle to create an encryption key, it ensures that only the person with the other entangled particle can decode the message and “the secret shared between these two sides is a proper secret,” he said.

At a news conference, Aspect said real-world applications like the satellite were “fantastic.”

“I think we have progress toward quantum computing. I would not say that we are close,” the 75-year-old physicist said. “I don’t know if I will see it in my life. But I am an old man.”

Google has reached a milestone in computing by achieving “quantum supremacy.” Caltech’s John Preskill, who coined that term, explains what that means.

Clauser, Aspect and Zeilinger have figured in Nobel speculation for more than a decade. In 2010 they won the Wolf Prize in Israel, seen as a possible precursor to the Nobel.

The Nobel committee said Clauser developed quantum theories first put forward in the 1960s into a practical experiment. Aspect was able to close a loophole in those theories, while Zeilinger demonstrated a phenomenon called quantum teleportation that effectively allows information to be transmitted over distances.

Zeilinger cautioned that it only works for tiny particles.

“It is not like in the ‘Star Trek’ films [where one is] transporting something, certainly not the person, over some distance,” he said.

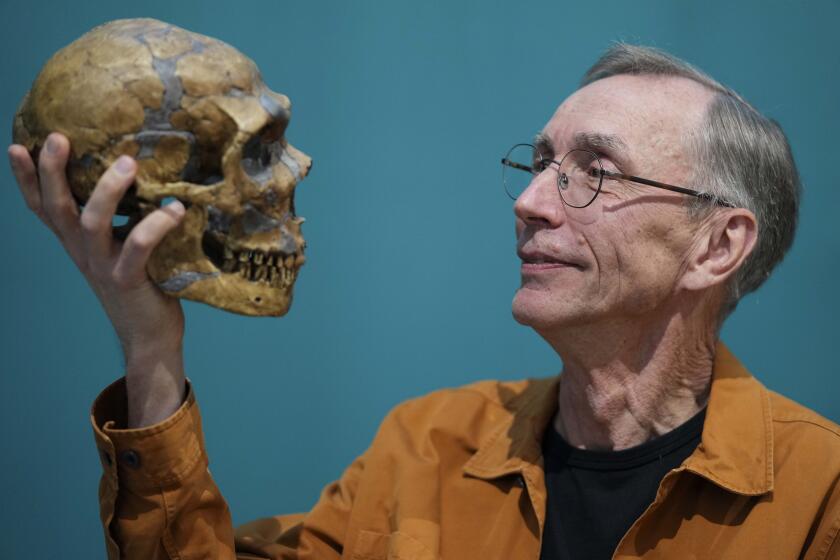

Svante Paabo’s discoveries on human evolution provided key insights into our immune system and what makes us unique compared with our extinct cousins.

A week of Nobel Prize announcements kicked off Monday with Swedish scientist Svante Paabo receiving the award in medicine for unlocking secrets of Neanderthal DNA that provided key insights into our immune system.

The prize for chemistry will be awarded Wednesday and literature on Thursday. The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the economics award the following Monday.

The prizes carry a cash award of 10 million Swedish kronor (nearly $900,000) and will be handed out on Dec. 10. The money comes from a bequest by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.