Here’s why scientists aren’t ‘crazy scared’ about monkeypox

- Share via

The monkeypox outbreak has captured the attention of an anxious public that’s struggling to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and is on high alert for the next virus that might upend our lives.

Fortunately, professionals are a lot calmer about monkeypox than the armchair pundits.

“In the last couple of years, everybody’s become a virologist,” said Paula Cannon, an actual virologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. “We don’t have to get crazy scared.”

Unlike the situation two years ago with the then-novel coronavirus, scientists are already familiar with this virus. They know monkeypox is nowhere near as transmissible as COVID-19, nor is it particularly deadly. They know how it spreads and how it can be stopped.

The outbreak intrigues people like Cannon for a very specific reason: They want to understand why it’s suddenly cropping up in unexpected places in North and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Australia.

U.S. and European health officials identify a number of cases of monkeypox, an illness previously limited mostly to central and western Africa.

Thousands of people contract monkeypox every year from close contact with infected people or animals, primarily in rural parts of western and central Africa. Even in areas with extremely limited access to healthcare, the survival rate is well over 90%.

Cases have been found in the U.S. and Europe before, but they’ve always been quickly linked to individuals who recently traveled to a place where the virus is endemic, or who interacted with infected animals.

The last major U.S. monkeypox outbreak, in 2003, was traced to pet prairie dogs who contracted the virus from infected animals imported from Ghana to Texas as pets. All 47 human patients survived.

The current outbreak, in which more than 400 cases have been reported worldwide, is a little different. Few if any of the patients have traveled to areas where the virus is known to be present, or had contact with infected animals.

The first U.S. case was documented in a Massachusetts man who recently traveled to Canada, where at least 26 cases have been confirmed so far.

California’s first case, an individual who health officials say recently traveled to Europe, turned up Tuesday in Sacramento County. At least 10 other cases have been identified in Colorado, Utah, Florida, Virginia, Washington state and New York City. Specimens are been sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmation testing.

Most of the patients in the current outbreak are in Europe, including more than 100 in the United Kingdom. Other cases have appeared in more than a dozen countries, including Spain, Portugal, Germany, the Netherlands, Mexico, Argentina, Israel and the United Arab Emirates, according to the World Health Organization and Global.health, an international research team funded by Google.

Everything you need to know about monkeypox.

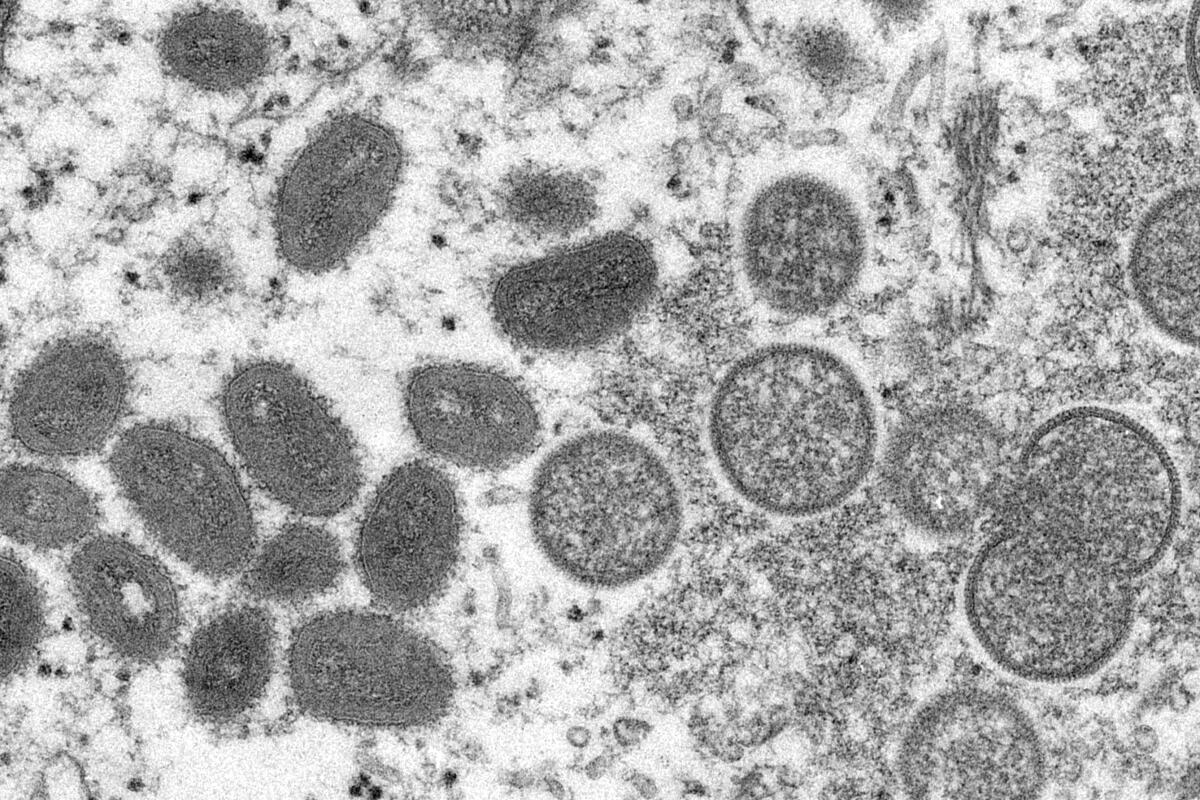

Despite the evocative name, monkeypox is more commonly found in rodents than in primates — a group of lab monkeys in Copenhagen just happened to be the first animals confirmed to have the pox back in 1958.

Within a week or two of exposure, infected people experience fevers, chills, muscle aches and swollen lymph nodes. A few days after the fever begins, patients develop distinctive pustule-like lesions that usually start on the face and spread across the body before scabbing over and falling away. Patients aren’t contagious until the first symptoms set in, and the disease typically runs its course in two to four weeks.

It’s a less lethal cousin of smallpox, a far more vicious virus that killed roughly 30% of those it infected. Thanks to vaccines, smallpox was declared eradicated worldwide in 1980.

Ironically, that success has opened the door for similar viruses, like monkeypox, to creep into the human population.

The vaccines that protect against smallpox also work against its weaker cousins, but they haven’t been part of standard childhood immunizations since the 1970s. There’s just been no need for them. As a result, most people under the age of 50 have no immunity to this kind of virus.

“The eradication of smallpox was of course one of the greatest achievements in public health history, but it also left the door open for other viruses to fill the void. As a result, we have waning population immunity to pox viruses,” said Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist who has studied monkeypox for the last two decades and leads the UCLA Center for Global and Immigrant Health.

In other words, she said with a rueful laugh, “no good deed goes unpunished.”

As disease outbreaks go, monkeypox packs far less power than COVID-19.

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, it was a brand new coronavirus. Scientists had to start from scratch to figure out what it was, how it spread and how it could be contained — all while a global health catastrophe unfolded.

In contrast, scientists already know that monkeypox spreads much less readily than the coronavirus and can be effectively contained with existing vaccines, which are still given to people at risk of coming into contact with the virus through travel or lab work.

The CDC has already stockpiled enough smallpox vaccine to combat a widespread outbreak. There are no specific treatments for monkeypox, but vaccination after exposure appears to lessen the disease’s severity.

The question for public health officials is: Where did the current outbreak come from, and what will the virus do next?

The search for answers is a lot like “looking back at a distant star,” Rimoin said. The events that led to today’s infections took place weeks ago; epidemiologists don’t know what’s happening right now that may or may not cause the disease to spread further.

You can’t get monkeypox by passing an infected person at the office or on the street. Transmission requires close physical contact or prolonged, intimate exposure to an infected person, or to their bedding or clothing. Hours of dancing in very close quarters could pass the virus; so could sexual contact. A significant number of the current reported cases appear to be linked to attendance at two raves in Europe.

An expert describes the unprecedented outbreak of monkeypox in developed countries as ‘a random event’ possibly sparked by risky sexual behavior.

At the moment, it appears “the virus got lucky — it found some big parties or festivals that enabled it to take off,” said Jamie Lloyd-Smith, a UCLA biologist specializing in infectious disease. “Then it flies under the radar because no one is looking for it. What doctor in Madrid sees somebody with a rash and thinks of monkeypox? Nobody, until last week.”

Early sequencing shows that the type, or clade, of monkeypox virus responsible for this outbreak is similar to that of a 2018 outbreak in Nigeria. It doesn’t seem to have mutated into a more easily transmissible form.

Monkeypox is endemic in rural, less densely-populated areas, Rimoin said. Will it behave differently among an urban, mobile population? Will the virus evolve as it moves through a new environment?

“That doesn’t necessarily mean that these things will come to bear. This is why we watch these viruses carefully,” Rimoin said. “We need to be able to ensure that we do not allow a pox virus to establish itself in places where it is not already endemic.”

The most valuable tools against further spread are vaccines and data. Outbreaks like this are the reason strong and constant public health surveillance is necessary.

“If we have good public health surveillance systems in place, and these things can be monitored, then we can nip things in the bud and stop things spreading,” Cannon said.