Pandemic gets tougher to track as COVID testing plunges

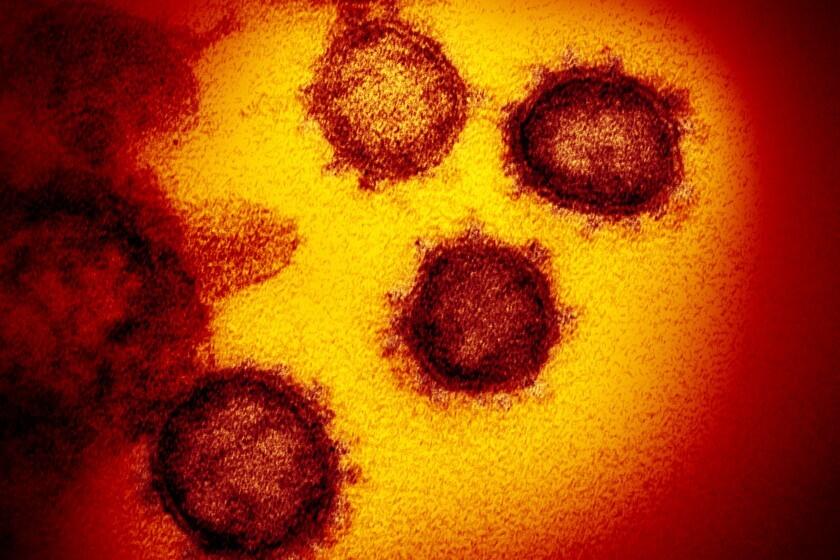

Testing for coronavirus infections has plummeted across the globe, making it much tougher for scientists to track the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and spot new, worrisome viral variants as they emerge and spread.

Experts say testing has dropped by 70% to 90% worldwide from the first to the second quarter of this year — the opposite of what they say should be happening with new Omicron subvariants on the rise in places such as the United States and South Africa.

“We’re not testing anywhere near where we might need to,” said Dr. Krishna Udayakumar, who directs the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University. “We need the ability to ramp up testing as we’re seeing the emergence of new waves or surges to track what’s happening” and respond.

As of Friday, reported daily cases in the U.S. were averaging 87,382 over the last week, up nearly 60% over the last two weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID Data Tracker.

But that is a vast undercount because of the testing downturn and the fact that tests are being taken at home and not reported to health departments. An influential modeling group at the University of Washington in Seattle estimates that only 13% of cases are being reported to health authorities in the U.S. — which would mean more than a half-million new infections every day.

The drop in testing is global, but the overall rates are especially inadequate in the developing world, Udayakumar said. The number of tests per 1,000 people in high-income countries is about 96 times higher than it is in low-income countries, according to the Geneva-based public health nonprofit FIND.

As L.A. County’s coronavirus cases continue to climb, infections are rising fastest among wealthier residents, a likely echo of previous waves in which a greater rate of higher-income people became infected with the virus first.

What’s driving the drop? Experts point to COVID-19 fatigue, a lull in cases after the first Omicron wave and a sense among some residents of low-income countries that there’s no reason to test because they lack access to antiviral medications.

At a recent media briefing by the World Health Organization, FIND Chief Executive Dr. Bill Rodriguez called testing “the first casualty of a global decision to let down our guard” and said that “we’re becoming blind to what is happening with the virus.”

Testing, genomic sequencing and delving into case spikes can lead to the discovery of new variants. New York state health officials found the super-contagious BA.2.12.1 subvariant after investigating higher-than-average case rates in the central part of the state.

Going forward, “we’re just not going to see the new variants emerge the way we saw previous variants emerge,” Rodriguez said.

The Omicron strain of the coronavirus keeps generating new subvariants. Here’s a look at how they stack up.

Testing increases as infections rise and people develop symptoms — and it falls along with lulls in new cases. Testing is rising again in the U.S. along with the recent surge.

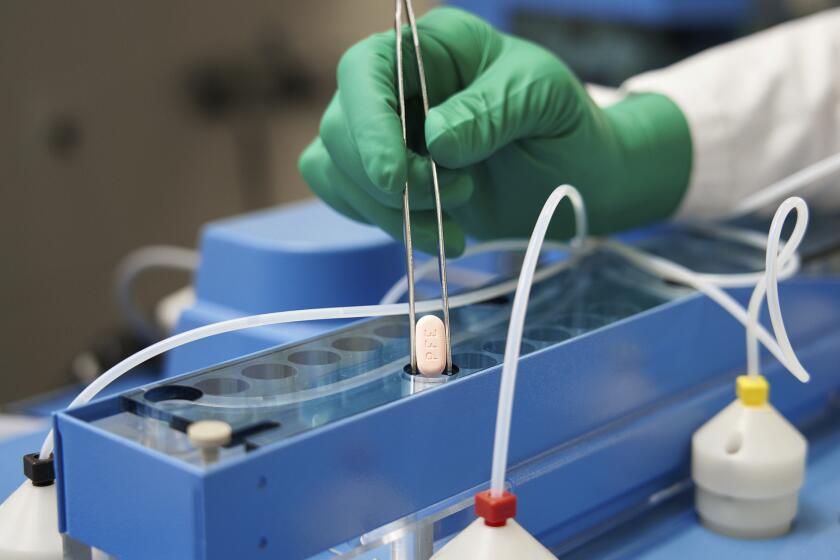

But experts are concerned about the size of the drop after the first Omicron surge, the low overall levels of testing globally and the inability to track cases reliably. While home tests are convenient, only tests sent to labs can be used to detect variants. If fewer tests are being done, and fewer of those tests are processed in labs, fewer positive samples are available for sequencing.

Also, home test results are largely invisible to tracking systems.

Mara Aspinall, managing director of an Arizona-based consulting company that tracks testing trends, said there is at least four times more home testing than PCR testing, and “we are getting essentially zero data from the testing that’s happening at home.”

That’s because there’s no uniform mechanism for people to report results to understaffed local health departments. The CDC strongly encourages people to tell their doctors, who in most places must report COVID-19 diagnoses to public health authorities.

Generally, though, results from home tests fall under the radar.

In Los Angeles and elsewhere, health workers are unable to see how many doses of Pfizer’s antiviral treatment are reaching the most vulnerable.

Reva Seville, a 36-year-old Los Angeles parent, tested herself at home this week after she began feeling symptoms such as a scratchy throat, coughing and congestion. After the results came back positive, she tested twice more just to be sure. But her symptoms were mild, so she didn’t plan to go to the doctor or report her results to anyone.

Beth Barton of Washington, Mo., who works in construction, said she’s taken about 10 home tests, either before visiting her parents or when she’s had symptoms she thought might be COVID-19. All came back negative. She shared the results with the people around her but didn’t know how to report them.

“There should be a whole system for that,” said Barton, 42. “We as a society don’t know how to gauge where we’re at.”

Aspinall said one potential solution would be to use technology such as scanning a QR code to report home test results confidentially.

Another way to keep better track of the pandemic, experts said, is to bolster other types of surveillance, such as wastewater monitoring and collecting hospitalization data. But those have their own drawbacks. Wastewater surveillance remains a patchwork approach that doesn’t cover all areas, and hospitalization trends lag behind cases.

Many public health officials say the success of COVID-19 sewage surveillance should make it a regular tool in tracking infectious diseases.

Udayakumar said scientists across the world must use all the tracking methods at their disposal to keep up with the virus and will need to do so for months or even years.

At the same time, he said, steps must be taken to boost testing in lower-income countries. Demand for tests would rise if access to antivirals were improved in these places, he said. And one of the best ways to increase testing is to integrate it into existing health services, said Wadzanayi Muchenje, who leads health and strategic partnerships in Africa for the Rockefeller Foundation.

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., said there will come a point when the world stops widespread testing for the coronavirus — but that day isn’t here yet.

With the pandemic lingering and virus still unpredictable, “it’s not acceptable for us to only be concerned about individual health,” he said. “We have to worry about the population.”

AP reporters Bobby Caina Calvan in New York and Carla K. Johnson in Seattle contributed to this report.