Patients can now access their health records online, but they may not understand them

- Share via

When Anna Ramsey suffered a flare-up of juvenile dermatomyositis, she feared it would lead to chemotherapy treatment that could compromise her already fragile immune system in the midst of a pandemic.

The Los Angeles resident waited three agonizing days for the results of a blood test to appear in her online patient portal — but she didn’t understand them. After an anxious night, she gave in and emailed her doctor, who responded with an explanation and a plan.

For Ramsey, now 24, the system was a mixed blessing. While she appreciates the quick access to her test results, she said she’d rather have an interpretation she can understand, “even if it takes a few days longer.”

Patients have long had a legal right to their medical records, though they often had to pay fees, wait weeks or sift through reams of paper to see them. But on April 5, a federal rule went into effect that requires healthcare providers to give patients like Ramsey electronic access to their health information upon request without delay, at no cost. Many patients may now find their doctors’ clinical notes, test results and other medical data posted to their electronic portal as soon as they are available.

Advocates herald the rule as a long-awaited opportunity for patients to control their data and health.

“This levels the playing field,” said Jan Walker, co-founder of OpenNotes, a group that has pushed for providers to share notes with patients. “A decade ago, the medical record belonged to the physician.”

But the rollout of the rule hasn’t always been smooth, as doctors learn that patients might see information before they do. Like Ramsey, some patients have felt distressed when seeing test results dropped into their portal without a physician’s explanation. And doctors’ groups say they are confused and concerned about whether the notes of adolescent patients who don’t want their parents to see sensitive information can be exempt — or if they will have to breach their patients’ trust.

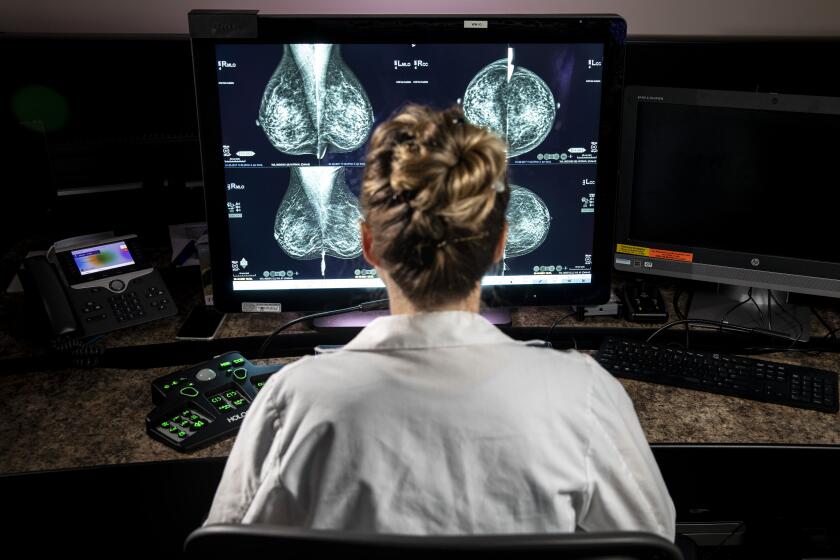

Radiologists have discovered a new side effect of COVID-19 vaccines: They make it more difficult to interpret mammogram results.

The new rule enables patients to access their health records through smartphone apps. It also prevents healthcare providers from withholding information from other providers or health information technology companies when a patient wants it to be shared. (Privacy rules under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which limit sharing of personal health information outside a clinic, remain in place, although privacy advocates have warned that patients who choose to share their data with consumer apps will put their data at risk.)

Studies have shown numerous benefits of note sharing. Patients who read their notes understand more about their health, better remember their treatment plan and are more likely to stick to their medication regimen. Patients who are nonwhite, older or less educated benefit the most.

For Sarah Ford, who has multiple sclerosis, reading her doctor’s notes helps her make the most of each visit and feel informed.

“I don’t like going into the office and feeling like I don’t know what’s going to happen,” the 34-year-old Pittsburgh resident said. If she wants to try a new medication or treatment, reading previous notes helps her prepare to discuss it with her doctor, she said.

While most doctors who have shared notes with patients think it’s a good idea, the policy has drawbacks. One recent study found that half of doctors reported writing their notes less candidly after they were opened to patients. Another study found that 1 in 10 patients felt offended or judged after reading a note.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Leonor Fernandez of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, said there is a “legacy of certain ways of expressing things in medicine that didn’t really take into account how it reads when you’re a patient.”

“Maybe we can rethink some of these,” she said. For instance, instead of saying “patient admits to drinking two glasses of wine a day,” she said, “why not just write ‘two glasses of wine a day’?”

Patients soon will have free electronic access to the notes their doctors write about them under a new federal requirement for transparency.

UC San Diego Health started phasing in open notes to patients in 2018 and removed a delay in the release of lab results last year. Overall, both changes have been uneventful, said Dr. Brian Clay, the chief medical information officer there.

“Most patients are agnostic, some are super-jazzed, and a few are distressed or have lots of questions and are communicating with us a lot,” Clay said.

There are exceptions to the requirement to release patient data, such as psychotherapy notes and notes that could harm a patient or someone else if released.

Dr. David Bell, president of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, believes it’s unclear exactly what qualifies as “substantial harm” to a patient, the standard that must be met for doctors to withhold an adolescent patient’s notes from a parent. Clarity is especially important to protect teenagers living in states with less restrictive laws regarding parental access to medical records, he said.

Most electronic medical records are not equipped to segregate sensitive material from other information that might be useful for a parent in managing their child’s health, he added.

Some doctors say that receiving devastating test results without counseling can traumatize patients.

Dr. James Kenealy, an ear, nose and throat doctor in central Massachusetts, recalled a time when a positive cancer biopsy result for one of his patients was automatically pushed to the patient’s portal over the weekend, blindsiding them both.

“You can give bad news, but if you have a plan and explain, they’re much better off,” Kenealy said.

Amid the fear and uncertainty brought on by the coronavirus, doctors and nurses are using narrative medicine to communicate more openly with their patients.

Such incidents aren’t affecting the majority of patients, but they’re not rare, said Dr. Jack Resneck Jr., an American Medical Assn. board trustee.

The AMA is advocating for “tweaks” to the rule, he said, like allowing brief delays in releasing results for a few of the highest-stakes tests, like those diagnosing cancer. The organization would also like to get more clarity on whether the harm exception applies to adolescent patients who might face emotional distress if their doctor breached their trust by sharing sensitive information with their parents.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, the federal agency overseeing the new rule, responded in an email that it has heard these concerns, but has also heard from clinicians that patients value receiving this information in a timely fashion. Patients can decide whether they want to look at results once they receive them or wait until they can review them with their doctor, the agency said.

The rule does not require giving parents access to protected health information if they did not already have that right under HIPAA, the agency added.

Patient advocate Cynthia Fisher believes there should be no exceptions to immediately releasing results, noting that many patients want and need test results as soon as possible, and that delays can lead to worse health outcomes. Instead of facing long wait times to discuss diagnoses with their doctors, she said, patients can now take their results elsewhere.

“We can’t assume the consumer is ignorant and unresourceful,” she said.

In the meantime, hospitals and doctors are finding ways to adapt. For instance, Massachusetts General Hospital is developing a guide to help patients interpret medical terminology in radiology reports, said Dr. William Mehan, a neuroradiologist.

In some cases, the rule allows doctors to ask patients whether they want their test results released immediately or if they’d rather wait for their doctor to communicate the result, said Jodi Daniel, a partner at the law firm Crowell & Moring. Some electronic health records make it possible for doctors to withhold test results if that would align with the patient’s preference, she said.

Chantal Worzala, a health technology policy consultant, said more is to come: “There will be a lot more conversation about the tools that individuals want and need in order to access and understand their health information.”

This story was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), a national newsroom that provides in-depth coverage of health issues and that is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KHN is the publisher of California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.