Child care has been safe during the pandemic. That could be a good sign for schools

- Share via

Sabrina Lira Garcia is proud to work as a clinical assistant in the COVID-19 ward of a Los Angeles hospital, but sometimes she wishes she could just stay home with her infant son until the pandemic is over.

But pulling her child from day care was not an option for Lira Garcia. She can’t put her career on hold. Her husband was born in Mexico and is undocumented, and the family pays monthly legal fees to help him get residency papers. If he were ever deported, she’d have to support 9-month-old Jeremiah by herself.

“I couldn’t afford to just stay home,” she said.

Lira Garcia and thousands of other essential workers have had no choice but to put their children in day care and run the risk that they’ll be exposed to the coronavirus. In effect, they’ve been part of an unplanned national experiment that’s deeply relevant to parents weighing the pros and cons of letting their children return to school this fall.

So far, it seems fairly successful. Considering the number of kids at child-care centers in the U.S., the number of coronavirus outbreaks they’ve reported is low. Research to date suggests that children rarely get sick with COVID-19, and those under 10 aren’t very efficient at transmitting the disease to older family members.

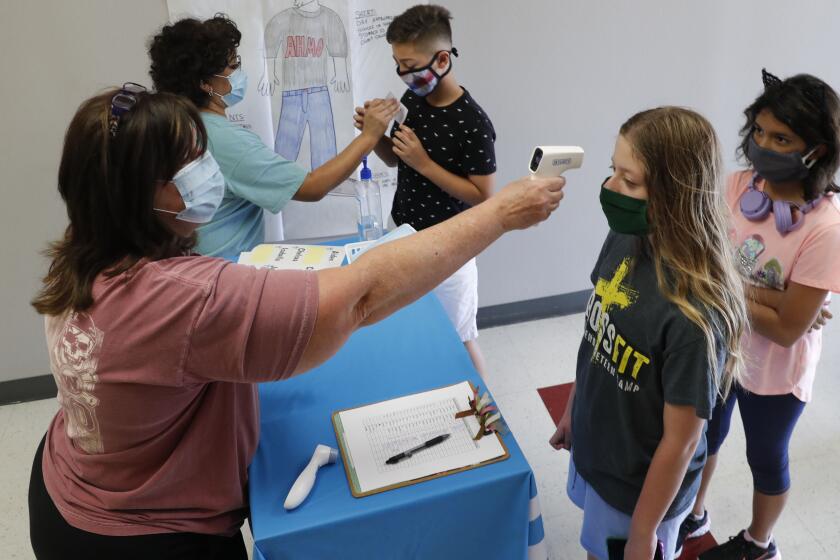

These dynamics — combined with additional precautions schools are taking regarding masks, classroom adaptations and keeping parents off campus — appear to make school and day care reasonable options for families with healthy younger children, experts say.

There are no guarantees, however. A week-long overnight camp in Georgia saw an outbreak in June despite several measures to mitigate risk. At least 51% of campers between the ages of 6 and 10 became infected with the coronavirus, as were 44% of attendees ages 11 to 17. About one quarter of those infected were asymptomatic, according to a report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Georgia Department of Public Health.

The key factor for parents to consider is how much the virus is spreading in their community, experts said.

Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the CDC, defines a “hot spot” as an area where more than 5% of coronavirus tests come back positive.

Here’s what scientists know about kids’ potential to spread the coronavirus and the risks of sending them back to school amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Allowing students to return to campus wouldn’t be wise “if you’re in the hottest of the hot zones, and you have massive outbreaks,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, the incoming dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. “Even if the kids are all right, you still need to have teachers and staff in elementary schools.”

But if the community transmission rate is low, “then I would have a lower threshold of getting K-5 back in person than I would, for instance, getting high school back,” he said, adding that “child-care centers are probably reasonably safe.”

Day cares remained open in California even after most schools shut down. As of July 22, about 33,300 facilities had the capacity to care for up to 720,882 children. Up until that date, the state recorded 1,365 COVID-19 cases linked to child-care centers, including 261 cases among children.

During the same time period, 9% of California’s 425,616 total cases were among people under age 18, and there were no coronavirus-related deaths reported in this age range. (The state’s first juvenile COVID-19 -related death was reported last week.)

In Los Angeles County, 268 cases — including 75 children — had been reported in the 7,238 day-care facilities that were open as of the end of July. Children under 5 account for fewer than 1% of all hospitalizations in the county, according to data presented by Barbara Ferrer, director of the county’s public health department.

The picture is similar in other states that have tallied outbreaks in child-care centers, including Texas and Ohio.

But the low case counts don’t mean that COVID-19 “is a completely benign disease in children,” Ferrer said. “We still have a lot to learn about the short- and long-term impacts of the virus.”

There’s a “big void” of information about how the virus spreads among small children and between children and older people, said Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, chief medical officer of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

“We don’t quite understand the infection dynamics, and we don’t really know the transmission dynamics,” he said, so parents will have to balance the relative lack of information against their own need for child care.

Israeli scientists say they can mimic the effects of a vaccination campaign if certain people willingly get infected with the coronavirus and recover.

Adding to the stress of these decisions, parents may not want children to see grandparents or other relatives who have helped take care of them in the past for fear of exposing them to the virus, Gunzenhauser said.

Ricardo Rizzo runs a child-care center with his wife and two daughters in the Panorama City neighborhood of Los Angeles. After the initial statewide shutdown in March, Rizzo and his family closed the center for two weeks to stock up on food and cleaning supplies. They also set up a sanitizing station outside the center and scheduled new cleaning routines.

Despite those precautions, the center still lost eight children because of layoffs, shortened work hours and parental fear about the virus. Eighteen kids are still in his care, Rizzo said, ranging in age from babies to a preteen.

The families who rely on the center are low-income and receive state subsidies to pay for child care. Nearly all have jobs deemed essential, such as grocery workers and certified nursing assistants. Some have multiple jobs.

“We feel blessed because we’re helping them by taking care of their kids,” Rizzo said.

So far, the center and its families have been COVID-free, Rizzo said. He finds comfort in “following the protocol” — adult caretakers wear masks, do a deep clean once a day and keep parents outside the facility when dropping off and picking up their children. He also lets his center’s families know they should be taking precautions as well.

“I say we have to work together,” Rizzo said. “If we do it here, you have to do it at home.”

Infections can still break through the child-care bubble.

Anna C., a 30-year-old IT worker in Kent, Wash., who asked that her last name not be used, tried to keep her 4-year-old and 20-month-old sons home until the toddler fell off a bed and split his lip while Anna and her husband were on separate conference calls.

Realizing they couldn’t work and safely watch their sons at the same time, the couple decided to send the kids back to child care in late April. They had to pull them out again a week later, after the spouse of an employee tested positive for COVID-19. No further infections arose during a two-week quarantine, so they sent the children back again.

“This is going to happen with any day care center or provider,” Anna said. “It’s just the new reality.”

Almendrala writes for Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation and is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.