Coming soon: The first pictures of the sun’s north and south poles

- Share via

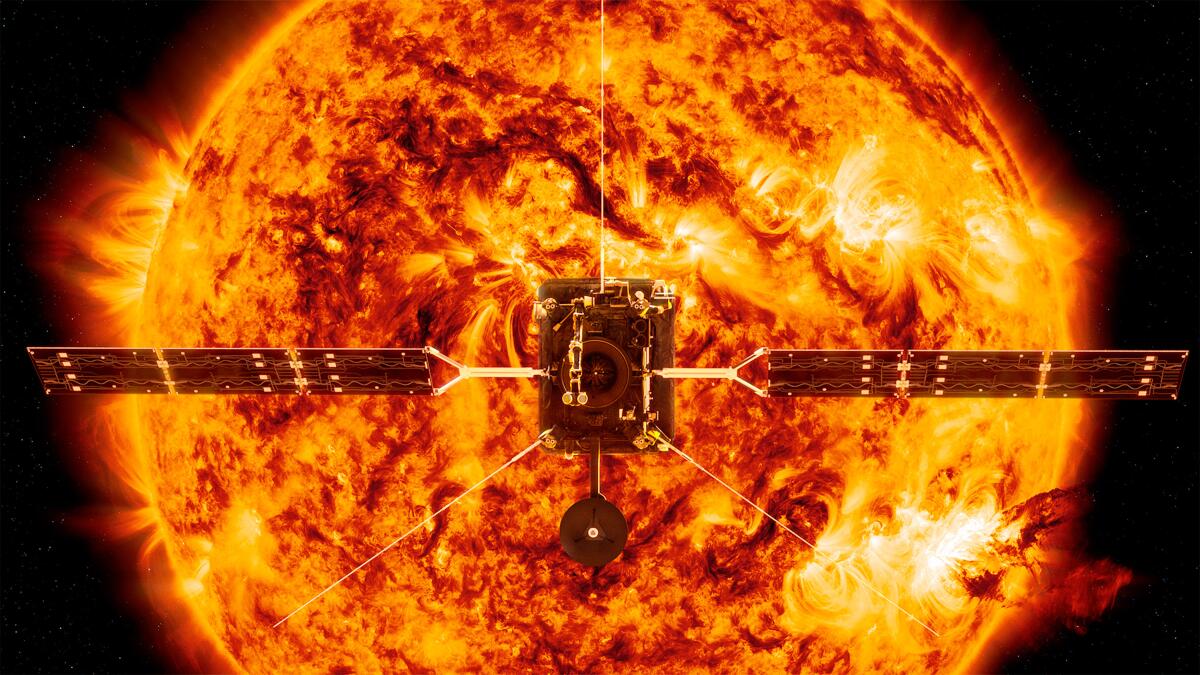

Europe and NASA’s Solar Orbiter rocketed into space Sunday night on an unprecedented mission to capture the first pictures of the sun’s elusive poles.

The $1.5-billion spacecraft will join NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, launched 1½ years ago, in coming perilously close to the sun in order to unveil its secrets.

Solar Orbiter will maneuver into a unique out-of-plane orbit that will take it over both of the sun’s poles, neither of which has been photographed before.

Together with powerful ground observatories, the two sun-staring spacecraft will be like an orchestra, according to Gunther Hasinger, the European Space Agency’s science director.

“Every instrument plays a different tune, but together they play the symphony of the sun,” Hasinger said.

Solar Orbiter was made in Europe, along with nine of its science instruments. NASA provided the 10th instrument and arranged the late-night launch from Cape Canaveral.

Nearly 1,000 scientists and engineers from across Europe gathered with their U.S. colleagues under a full moon as it blasted off, illuminating the sky for miles around. Crowds also jammed nearby roads and beaches.

Europe’s project scientist Daniel Mueller was thrilled, calling it “picture perfect.” His NASA counterpart, scientist Holly Gilbert, exclaimed, “One word: Wow.”

Solar Orbiter — a boxy 4,000-pound spacecraft with spindly instrument booms and antennas — will swing past Venus in December and again next year before flying past Earth. Each time, it will use a planet’s gravity to alter its path to achieve its unusual orbit.

Full science operations will begin in late 2021, with the first close solar encounter in 2022 and more every six months.

At its closest approach, Solar Orbiter will come within 26 million miles of the sun, well within the orbit of Mercury.

Parker Solar Probe, by contrast, has already set a record by passing within 11.6 million miles of the sun, and it’s shooting for a slim gap of 4 million miles by 2025. It will penetrate the sun’s corona, or crown-like outer atmosphere. But it’s flying nowhere near the poles.

That’s where Solar Orbiter will shine.

The sun’s poles are pockmarked with dark, constantly shifting coronal holes. They’re hubs for the sun’s magnetic field, flipping polarity every 11 years.

Solar Orbiter’s head-on views should finally yield a full 3-D view of the sun, 93 million miles from our home planet.

“With Solar Observatory looking right down at the poles, we’ll be able to see these huge coronal hole structures,” said Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division. “That’s where all the fast solar wind comes from ... It really is a completely different view.”

To protect the spacecraft’s sensitive instruments from the sun’s blistering heat, engineers devised a heat shield with an outer black coating made of burned bone charcoal similar to what was used in prehistoric cave paintings. The 10-by-8-foot heat shield is just 15 inches thick, and made of titanium foil with gaps in between to shed heat. It can withstand temperatures up to nearly 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Embedded in the heat shield are five peepholes of varying sizes that will stay open just long enough for the science instruments to take measurements in X-ray, ultraviolet, visible and other wavelengths.

The observations will shed light on other stars, providing clues as to the potential habitability of worlds in other solar systems.

Closer to home, the findings will help scientists better predict space weather, which can disrupt communications.

“We need to know how the sun affects the local environment here on Earth, and also Mars and the moon when we move there,” said Ian Walters, project manager for Airbus Defence and Space, which designed and built the spacecraft. “We’ve been lucky so far the last 150 years,” since a colossal solar storm last hit. “We need to predict that. We just can’t wait for it to happen.”

The U.S.-European Ulysses spacecraft, launched in 1990, flew over the sun’s poles, but from farther afield and with no cameras on board. It’s been silent for more than a decade.

Europe and NASA’s Soho spacecraft, launched in 1995, is still sending back valuable solar data.

Altogether, more than a dozen spacecraft have focused on the sun over the past 30 years. But only technology has made it possible for elaborate spacecraft such as Parker and Solar Orbiter to get close to the sun without being fried.

Fox considers it “a golden age” for solar physics.

“So much science still yet to do,” she said, “and definitely a great time to be a heliophysicist.”