New coronavirus spreads as readily as 1918 Spanish flu and probably originated in bats

Chinese scientists racing to keep up with the spread of a novel coronavirus have declared the widespread outbreak an epidemic, revealing that in its early days at least, the disease’s reach doubled every week.

By plotting the curve of that exponential growth and running it in reverse, researchers reckoned that the microbe sickening people across the globe has probably been passing from person to person since mid-December 2019.

Scientists in China are also closing in on the source of the aggressive new germ — bats.

The furry flying mammals may have been the original host of the coronavirus now crisscrossing the world, says one of three scientific studies released on Wednesday. But it may be another wild animal sold in Wuhan City’s Huanan Seafood Market that served up the virus to humans, who quickly began passing it to others through close contact.

The new studies, coming just five days after Chinese research teams offered their first detailed analyses of the virus known as 2019-nCoV, offer genetic and other evidence to suggest that Chinese health authorities probably caught the virus soon after it made its jump to humans. And it supports the theory that something in the Huanan market served as a bridge for the virus to cross between bats and humans.

Such evidence is consistent with the Chinese government’s public assertions about the sudden appearance and spread of a virus that has sickened as many as 9,000 and claimed at least 170 lives in China and six other countries. Chinese authorities have said they believe that Wuhan’s principal “wet market” is the cradle of the outbreak, and they have no evidence that the new virus spread earlier anywhere else.

There are many things scientists really wish they knew about the coronavirus that has sickened thousands of people and caused at least 132 deaths.

All three of the new studies — two published by the British journal Lancet and a third in the New England Journal of Medicine — were conducted by scientists working in China. And all focused on some of the first patients seen with a pneumonia caused by 2019-nCoV.

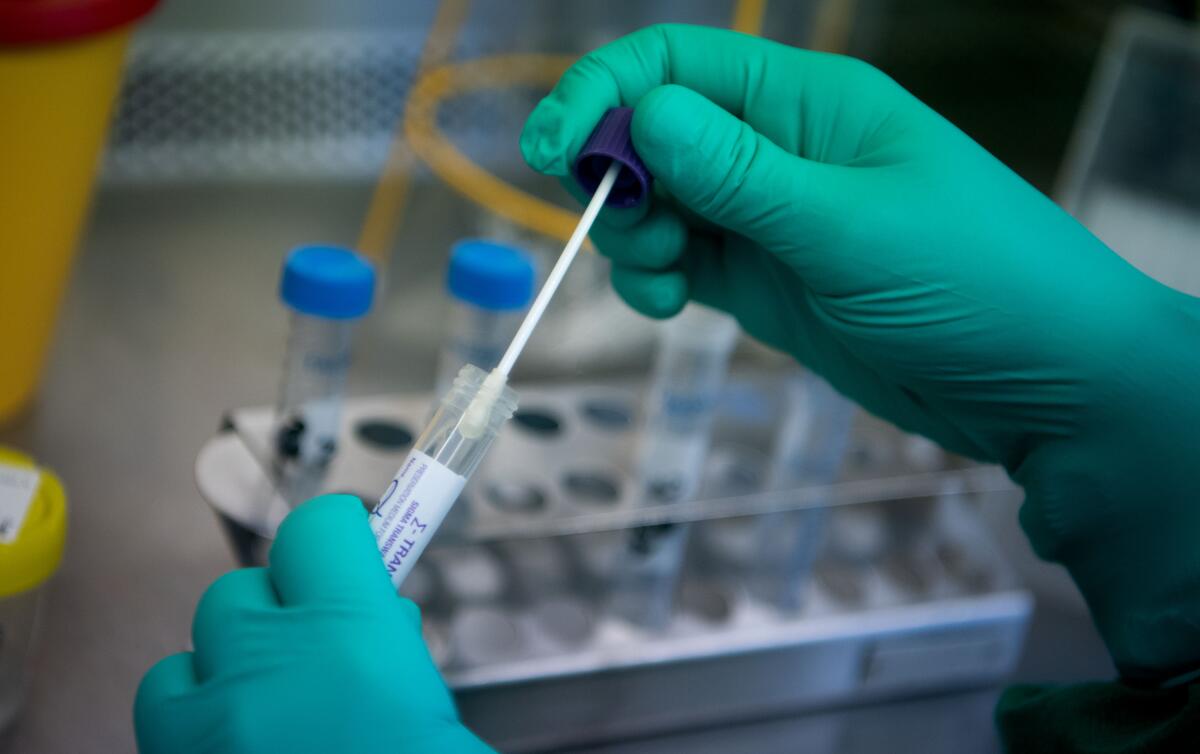

One of the studies published in Lancet probed the genetic connections among viral samples drawn from nine infected patients, eight of whom had visited the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan.

The second study in Lancet culled data on the disease progression and outcomes of 99 infected patients who were admitted to Jinyintan Hospital in Wuhan with symptoms of pneumonia.

The New England Journal of Medicine study, performed by researchers at China’s leading public health agency, mapped the early spread of pneumonia cases caused by the virus and used the results to create a transmission timeline. That accounting offered the most authoritative gauge to date of the emerging epidemic’s rate of growth.

The new findings underscore the fact that it may take stern domestic measures to bring the fast-moving virus under control in China.

One of the research teams calculated that in its early stages, the epidemic doubled in size every 7.4 days. That measure, called the epidemic’s “serial interval,” reflects the average span of time that elapses from the appearance of symptoms in one infected person to the appearance of symptoms in the people he will go on to infect. In the early stages of the outbreak, each infected person who became ill is estimated to have infected 2.2 others, according to the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That makes the new coronavirus roughly as communicable as was the 1918 Spanish flu, which killed 50 million and became the deadliest pandemic in recorded history.

The 1918 flu was one the worst pandemics in history, infecting one-third of the world’s population. How cities responded to the crisis in 1918 provides lessons on handling COVID-19 today.

The new epidemic, however, is moving more slowly than the Spanish flu. That’s because 2019-nCoV takes longer to induce coughing, fever and breathing difficulties in a newly infected victim.

“It’s concerning that case reports are increasing, and increasing in a way that’s consistent with pretty efficient human-to-human transmission,” said Derek Cummings, a University of Florida expert in the spread of infectious diseases.

If the coronavirus outbreak in China were a Hollywood movie, now would be time to panic. But in real life, most Americans have no need, experts say.

While much more needs to be known about the coronavirus’ spread, the early numbers offer a glimpse of the challenge ahead, Cummings said.

To halt the growth of the virus’ spread and allow the epidemic to burn itself out, health officials in China are going to have to cut the rate at which the germ is passing from person to person by more than half. That could be done by quarantining anyone who’s ill, by closing down schools or workplaces or social gatherings, or eventually by administering a vaccine that does not currently exist.

Even under the most optimistic scenarios, Cumming said, “a lot of control needs to take place.”

China’s public health authorities acknowledged as much on Wednesday.

“Considerable efforts to reduce transmission will be required to control outbreaks if similar dynamics apply elsewhere,” a team led by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Beijing wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

They noted that reducing the spread of the new virus is made harder by the apparent presence of many mild infections. If not all who are infected get very sick — as appears to be the case — many will go out in the world and spread the virus inadvertently.

The team also cited “limited resources for isolation of cases and quarantine of their close contacts” as an impediment.

Despite suspicions prompted by its secretive management of the SARS outbreak in 2003, the Chinese government has insisted it responded quickly to the appearance of a new virus, and has held nothing back from the Chinese public or international community.

The World Health Organization has said that China notified it on Dec. 31 that the agency it was seeing cases of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan. Chinese authorities closed down the Huanan Seafood Market on Jan. 1. That would be only about two weeks after the virus first jumped to humans in Wuhan, if the new calculations are correct.

Health officials in China identified a novel coronavirus as the cause of the outbreak less than a week later, and on Jan. 23, the government blocked transportation in and out of Wuhan.

In an effort to stem further spread of 2019-nCoV, officials imposed a quarantine of unprecedented size and scope, shutting down transportation in and out of other cities in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located. The controversial blockade has affected about 50 million people, and has been criticized for being both too broad and too late to bottle up the virus.

On Tuesday, American officials exhorted Chinese officials to share their trove of biological samples and genetic findings with U.S. and international researchers. Within hours, the Chinese government shifted gears and asked the World Health Organization to send international experts to assist with research and help contain the epidemic.