Nine science stories to watch in 2019

From the edge of Earth to the frontier of the solar system, there’s plenty of science awaiting us in 2019.

Some projects have been years in the making. Others were pushed to the forefront by the demands of a fast-changing world.

Either way, they promise to change our view of the world — and inspire new questions no one previously thought to ask.

Here’s a look at some of the science stories we’ll be following in the new year.

New Horizons pays historic visit to Ultima Thule

While you’re sipping champagne this New Year’s Eve, a spacecraft 4 billion miles from Earth will be making history.

NASA’s New Horizons probe is scheduled to fly past a mysterious object known as Ultima Thule at 9:33 p.m. Pacific time on Dec. 31. Situated roughly 1 billion miles beyond Pluto, it will be the most distant object ever visited by humankind.

Ultima Thule is located in the Kuiper Belt, a doughnut-shaped region of icy bodies encircling the sun beyond Neptune’s orbit. Because these worlds are so small and far away, scientists know virtually nothing about them.

“We know Ultima’s orbit. We know it is about 20 miles across and irregularly shaped and red in color, and that’s it.” said Alan Stern, the principal investigator for the New Horizons mission.“I just told you everything we know about Ultima Thule.”

That will all change at the beginning of 2019, when data from New Horizons reaches Earth.

“We are going to go from a dot in the distance on New Year’s Eve to maps on Jan. 2,” said Stern, who is based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. “Buckle up and enjoy the ride.”

Redefining the metric system

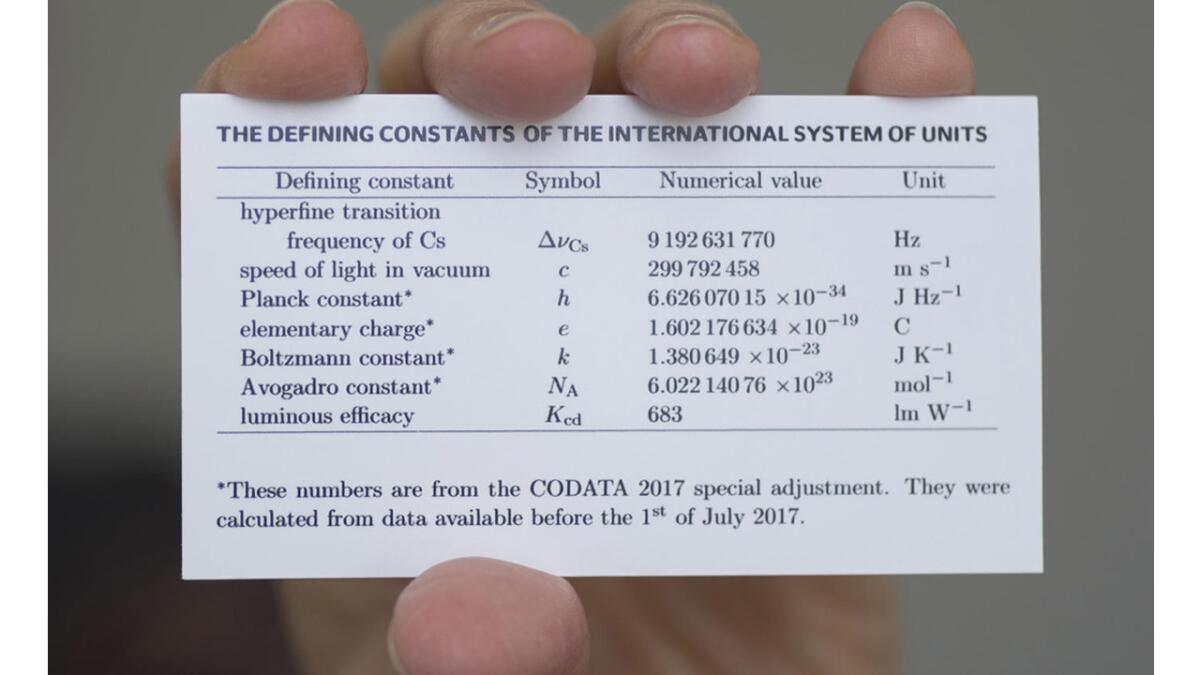

On May 20, the international metrology community will change the definitions of four basic units of measurement: the kilogram (mass), the Kelvin (temperature), the mole (amount) and the ampere (electrical current).

These changes won’t immediately affect your life — a pound of coffee will remain the same — but scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md., say the shift represents a “turning point for humanity.”

From that day forward, these four components of the International System of Units, better known as the metric system, will be based on fundamental properties of physics that are constant throughout the cosmos.

The precedent was set in 1967, when the definition of a second was changed to the length of time required for a cesium-133 atom to complete 9,192,631,770 oscillations. The meter followed in 1983, becoming the distance traveled by light in one 299,792,458th of a second. Anywhere in the universe, these two units of measurement would remain the same.

The new definitions coming in 2019 are based on similar principles. The kilogram will be defined using Planck’s constant, and an ampere will be a measure of how many electrons pass through a single point in one second.

“The idea is to build a measurement system for all civilizations,” said institute physicist Stephan Schlamminger, “even extra-terrestrial ones.”

Antarctica gets ready for its close-up

It’s summer in Antarctica, which means it’s the season for science. In January, two big expeditions will begin to explore pressing questions about how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is changing — and what that means for the rest of the planet.

One expedition is a $25-million U.S.-U.K. collaboration to study the Thwaites Glacier. In recent years, scientists have issued warnings that the Florida-sized river of ice may be on the verge of a centuries-long collapse that could raise global sea levels by 10 feet. Now, researchers will inspect the glacier up close and personal. They’ll do it with the help of the Nathaniel B. Palmer, a National Science Foundation research vessel that can break up heavy ice. They’ll also use an autonomous underwater vehicle — named Boaty McBoatface by the good people of the internet — to peer beneath the glacier’s floating ice shelf and study how the ocean is eating away at the ice from below.

In addition, scientists will “collaborate” with seals by outfitting them with monitoring equipment that gathers data as they forage.

About 1,100 miles away, on the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula, another international team will study the Weddell Sea, the birthplace of a Delaware-sized iceberg that broke off from the Larsen C ice shelf in 2017. The ice shelf, like others that fringe Antarctica, helps slow glacial ice’s slide into the sea.

Scientists will use different underwater robots to observe the ice shelf as it interacts with the ocean and see how much it’s thinning. They’ll also explore the sea’s rich ecosystem, which some would like to see protected from commercial fishing.

Time permitting, the researchers will investigate the whereabouts of the Endurance. Ernest Shackleton and his crew abandoned the ice-bound ship before it sank more than a century ago, and no one has seen it since. Perhaps that will change this year.

New ways to prevent opioid abuse

The statistics of opioid dependency and death remain grim. And let’s not sugarcoat this: The data suggest things will likely get worse before they get better. In 2019, government agencies, health policy experts and medical researchers will be looking for ways to change the trajectory of this American crisis.

Starting Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will launch a raft of new policies governing the prescribing and dispensing of opioid narcotics to patients covered by Medicare Part D insurance — largely people over 65 and those receiving Social Security disability benefits. Those will trigger new alerts for patients filling narcotic pain relief prescriptions that exceed certain strengths and durations, and in some cases a consultation between the doctor and the pharmacist will be required.

In early February, the National Institutes of Health will host a major meeting on the future of addiction and pain therapies. The goal will be to identify promising targets, find potential biomarkers and take a hard look at what has worked and what hasn’t.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force will be looking for ways to head off cases of opioid abuse in the first place. This independent expert panel, which advises the government on medical matters, has posted its plan for investigating ways to minimize the use of opioids, or find alternatives so more patients don’t start taking them in the first place. The review is expected to get underway after the public comment period closes on Jan. 16.

The overdose medication Narcan has made a significant dent in preventing fatal overdoses involving heroin and most prescription opioids. But even at higher doses, Narcan is often ineffective against fentanyl and other super-powerful synthetic opioids. Federal agencies have invested millions of dollars in a drug called nalmefene, which they hope will fill this void. Pivotal studies of its safety and effectiveness are planned for the coming year.

Health officials are worried about their inability to counter fentanyl’s growing stranglehold on people with addiction. And there’s an even darker scenario: the use of fentanyl or similar drugs in a large-scale terrorist attack. In 2002, Russian forces pumped a vaporized form of fentanyl into a movie theater where Chechen rebels were holding 800 hostages. The counterattack killed about 100 hostages and sent hundreds more to the hospital, making clear fentanyl’s potential as a weapon of mass destruction.

The periodic table turns 150

It’s time to step back and appreciate one of the great marvels of science. That’s why the United Nations has designated 2019 the International Year of the Periodic Table.

The choice wasn’t arbitrary: 2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the theory around which the table is organized. Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev discovered the cyclical pattern — or periodicity — in how the elements behave as they increase in atomic weight. For instance, the elements at the end of each row form stubbornly inert noble gases, while the metals in the middle of the table increase in hardness and melting points from left to right.

This way of arranging the periodic table predicted the existence of elements that had yet to be discovered and showed people how groups of elements shared similar chemical properties, says Chris Ober, a materials chemist at Cornell University. Over time, he said, “it became even more powerful than the inventors realized.”

The opening ceremony for events will take place Jan. 29 in Paris, and feature, among other things, a tribute to 8th century alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan, who discovered sulfuric and nitric acids. In February, a symposium in Murcia, Spain, will highlight the contributions of female scientists to the periodic table.

In addition, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry will celebrate its 100th birthday by honoring rising young chemists and hosting an online Periodic Table challenge for students.

One of the organization’s primary duties is certifying new elements, but chemists probably won’t find any new ones in 2019, Ober said. Scientists filled in the seventh row of elements in 2015, rounding out the Periodic Table as we know it. That has helped get people excited for year’s festivities, Ober said: “It sort of captured their imagination.”

Youth climate lawsuit may finally go to trial

A landmark climate lawsuit has been inching closer to trial for four years. And in 2019, it may get its day in federal court at last — unless judges toss the case once and for all.

The suit was brought by 21 young people who say the U.S. government is violating their constitutional rights by promoting the use of fossil fuels in spite of the dangers posed by climate change. The plaintiffs make the novel argument that federal authorities are legally obligated to protect the atmosphere as part of the public trust.

After years of legal maneuvering and numerous failed attempts by the Obama and Trump administrations to have the case thrown out, a court date was set for October 2018 in Eugene, Ore. But on the eve of the trial, the federal government requested a stay from the Supreme Court. The justices denied the request, but a separate appeal to the 9th Circuit Court has kept the case in legal limbo.

If the trial proceeds, it will feature dozens of scientists on both sides. Experts for the plaintiffs will offer evidence linking the government’s actions to injuries suffered by the youth, which include exposure to unhealthy wildfire smoke, flooding brought on by increasingly extreme weather, and the emotional distress of facing a future made more uncertain by global warming. Those testifying for the defense will not deny that humans are fueling climate change by releasing heat-trapping greenhouse gases. But they will argue that the U.S. government is neither fully responsible for the effects nor fully capable of remedying the problem.

The young plaintiffs are not after money. If they win, they want the judge to order the government to slash greenhouse gas emissions to help ensure a safe and stable climate.

A traffic jam on the moon

If you thought going to the moon was passé, think again.

In 2019, China, India and Israel are all expected to land unmanned spacecraft on the lunar surface, while NASA steps up its efforts to return a human crew to the moon by 2028.

China’s mission will land first. The Chinese National Space Administration launched Chang’e-4 to the far side of the moon in early December, and the craft is now in lunar orbit. Touchdown is expected in early January. If all goes as planned, it will be the first mission to touch down on the side of the moon that never faces Earth — and it could reveal new details about the moon’s largest and deepest crater.

The Indian Space Research Organization is scheduled to launch its second mission to the moon on Jan. 31. Chandrayaan-2 will include an orbiter, a lander and a 6-wheeled rover. Together, these craft will measure moonquakes, study the lunar atmosphere and take the moon’s internal temperature.

Later in the year, Israel will send its first spacecraft to the moon. Built by the Israeli nonprofit SpaceIL in collaboration with the state-funded Israel Aerospace Industries, the lander will be lightest ever sent to the moon, weighing in at just 1,322 pounds (including fuel). The mission was a finalist for the Lunar XPrize, a modern-day race to the moon sponsored by Google. Google pulled funding for the competition in March of 2018, but the SpaceIL team decided to move forward anyway.

NASA has no firm plans to send a spacecraft to the moon this year, but it will start seeking proposals for a system that can transport humans to the lunar surface for the first time since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. The space agency’s formal request for help from its industry partners is scheduled to go out on Jan. 7.

How to move forward with gene editing

Few were expecting that 2018 would see the birth of twin girls whose DNA had been edited in the lab when they were just days-old embryos. But it did, and now the scientific and bioethical questions raised by gene editing promise to be front and center in 2019.

The claim by Chinese biophysics researcher He Jiankui that he altered the girls’ DNA to protect them against HIV prompted China’s ministries overseeing health, science and technology to denounce his actions as “extremely abominable.” They shut down labs associated with his research, and he has not been seen in public since.

Even so, researchers and scientific regulators will want to track the health of the twins and discern whether the gene-editing procedure introduced any “off-target” DNA anomalies or other unintended errors. They’ll also want to establish just how many children among us are the products of “germline editing” — making changes in DNA that can be passed down to future generations.

In the meantime, gene-editing research will continue. Japan recently issued its first-ever national guidelines on the subject, allowing — indeed, encouraging — its researchers to use gene-editing tools on human embryos. The guidelines limit the manipulation of embryos to be used in reproduction, but that restriction isn’t legally binding.

Other uses of gene-editing are considered ethically sound. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already given its stamp of approval to Luxturna, a gene therapy treatment for a rare form of blindness caused by a genetic mutation, and others are on track to follow suit. These include additional gene therapies for blindness, as well as ones for spinal muscular atrophy, cystic fibrosis and hemophilia.

Will money start pouring in for gun research?

If the trend continues, the coming year will bring more school shootings and more mass shootings. And those will keep the complex of related issues — gun access and storage, mental health, and violence prevention — front and center.

Philanthropies have responded to nearly 20 years of federal funding limits on firearms research with new private investments, and that money has begun to nurture a generation of public health researchers with expertise in these subjects. The questions they are probing — What concrete measures work to reduce firearms deaths? How do you identify individuals prone to suicide or violence? — are central to getting a handle on gun-related injuries. But answers don’t come easy when federal research funds (an average of $22 million per year between 2004 and 2015) are only 1.6% of the amount you’d expect for a scourge that claimed 39,773 lives in 2017.

Meanwhile, with the federal government still divided over gun policy, states are enacting laws and testing initiatives to protect schools and other public places from would-be shooters. The efforts range widely: Some states are intent on countering mass shootings by arming school administrators, while others are investing in more mental health screening and treatment for students. After the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., a growing number of states adopted “red flag” laws. These allow law enforcement, family members or other concerned parties to ask a judge to order the temporary removal of guns from people who may pose a threat to themselves or others. Thirteen states now have such laws on the books, and two more are considering them.

The coming year will see one federal gun-related initiative implemented, and it could limit the carnage of future gun rampages. In the first three months of 2019, those who own “bump stocks” — devices designed to make semiautomatic rifles capable of rapid, sustained firing — will be required to turn them in to the Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, Tobacco and Explosives, or to destroy them. The Trump administration announced the ban on the sale or ownership of the devices in December in response to their use in the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas, in which a gunman using a bump stock killed 58 concert-goers and wounded hundreds of others in a matter of minutes.