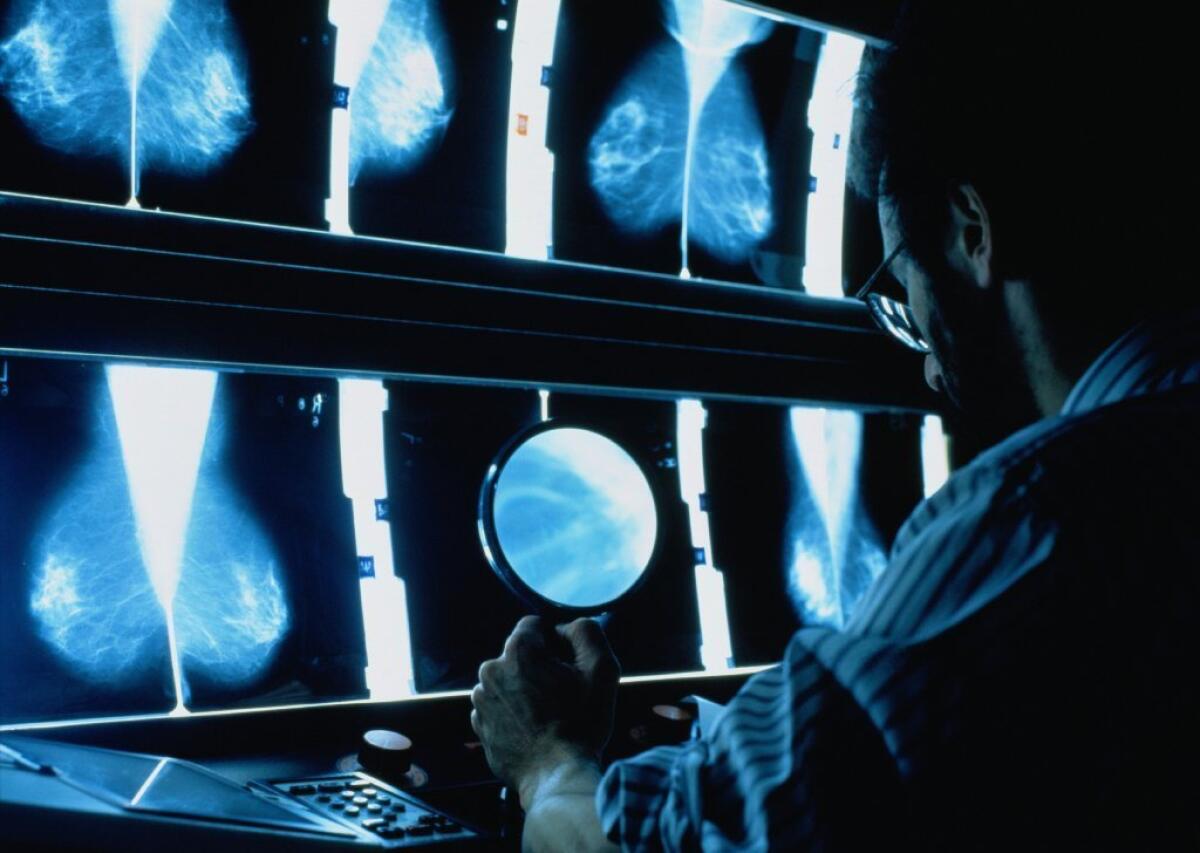

Breast cancer screening recommendations clarify science but muddy political waters

New federal recommendations suggest that the harms may outweigh the benefits when women get yearly mammograms before the age of 50. But they leave women and their physicians room to choose.

- Share via

The experts who sparked a passionate debate over the value of mammograms as a tool to screen for breast cancer are doubling down on the recommendations that earned them the ire of cancer groups, women’s groups and a large contingent in Congress.

The final advice of a federal task force reiterates that after all the risks and benefits are weighed, screening mammograms do the most good when women get them every other year from ages 50 to 74. For the majority of women — those whose risk of developing breast cancer is average at best — getting mammograms earlier or more often raises the likelihood of cancer scares and unnecessary follow-up treatments, the task force said.

For women older than 74, the panel said there’s insufficient scientific evidence to make a recommendation.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force said that some women in their 40s may elect to get mammograms after discussing the pros and cons with their doctors. But the group cautioned that for these women, screening mammograms catch few preventable cancers while raising the risk of false positives.

The panel also made clear that for women ages 40 to 74 who are at average risk of breast cancer, annual screening is more likely to lead to overtreatment than it is to save lives.

The new recommendations are likely to affect women’s decisions about getting mammograms in very real ways as they guide insurers’ decisions about what treatments to cover. The Affordable Care Act requires that the task force’s strongest recommendations — in this case, a mammogram every two years for women ages 50 to 74 — must be offered to insured women without co-payment.

That does not apply when the task force deems a treatment to have net benefits that are less than “moderate or substantial.” As a result, mammograms for women still in their 40s need not be offered without co-payment by insurers.

After years of fervent activism, public health campaigns and medical practice, the mammogram has become an annual ritual for many women older than 40 in the United States. For some breast cancer advocacy groups, the benefits of that ritual have become an article of faith.

So when the task force first questioned that conventional wisdom in 2009 and said screening could start later and take place less often, the result was confusion and controversy.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose physicians are most likely to counsel women about breast cancer screening, recommends annual mammograms starting at age 40, as does the American College of Radiology. After years of offering the same advice, the American Cancer Society changed its guidelines last year and now suggests yearly mammograms starting at age 45, switching to once every other year at age 55.

“The most important message is that women have a choice,” said Dr. Kenneth Lin, a family physician at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington. “If you’re a woman in your 40s, you could start at 40, wait till you’re 50 or start in between. Those are certainly reasonable choices, given the evidence we have.”

Not everyone was as receptive to the task force’s advice.

“I don’t endorse these guidelines,” said Dr. Catherine Dang, associate director of Cedars-Sinai’s Breast Cancer Risk Reduction Program. She said she would still advise her patients to get annual mammograms in their 40s.

Anticipating the new guidelines, Congress last month passed a law requiring health insurance companies to pay for annual mammograms for women in their 40s.

With prospects for such resistance looming, the task force painstakingly outlined the scientific evidence at hand and weighed the fine balance of potential benefits and harms for a range of screening regimens.

For every 1,000 women with an average risk of developing breast cancer, a mammogram every other year starting at age 40 and continuing until 50 might avert a single death from breast cancer, according to a detailed analysis published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine. But that benefit came with a cost — over 10 years, those screenings would lead to 576 false positives and 58 biopsies that would prove benign.

The most extreme risk is that women will wind up getting unnecessary treatment for breast cancer because the screening tests will find small tumors that would never have caused harm if they had gone undetected and were left alone. In a comparison of two groups of 1,000 women in their 40s — one that got mammograms every two years and the other that did not — the mammogram group would over a decade have two more women who underwent treatment that was fraught with risk and provided no benefit.

The recommendations do not address women with a family history of breast cancer or who otherwise face a heightened risk of breast cancer.

Dr. Michael LeFevre, the immediate past chairman of the task force, said the panel’s mandate is to assess the scientific evidence on screening tests, not to make decisions on insurance coverage or other politically charged matters.

“We cannot exaggerate our interpretation of the science to ensure coverage of a service,” the task force members wrote in an editorial that accompanied their analysis. “This would lead to confusion regarding the state of science versus the politics of coverage.”

Another editorial from the journal’s top editors emphasized that point as well, chiding those who accused the task force of restricting women’s access to mammography.

“Guidelines that mislead women about the net health benefits they can expect from mammography would disrespect our mothers, wives, daughters and sisters,” they wrote. “Let’s douse the flames and clear the smoke so that we can see clearly what the evidence shows and where we need to focus efforts to fill gaps in our knowledge” about breast cancer screening.

As the task force made clear, those gaps are substantial. The panel said it had insufficient scientific evidence to make recommendations on whether new forms of mammography, such as digital breast tomosynthesis, could shift the balance of risks and benefits. Nor could they offer recommendations on the value of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging to women with especially dense breasts.

And they lamented that the benefits and harms of mammography for women 75 and older were unclear because this population is so poorly represented in studies.

“When we’re not sure, what we don’t do is put expert opinion in to fill in the blanks,” LeFevre said. “Every other professional association does that.”

Twitter: @LATMelissaHealy

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.