Coronavirus Today: California’s pandemic politics

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Aug. 24. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

We’ve got three weeks to go until election day, when Californians will answer this fateful question: “Shall GAVIN NEWSOM be recalled (removed) from the office of Governor?”

There’s no mention of the coronavirus, but there might as well be. For many voters, Newsom’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic is what’s really on the ballot.

They’re unhappy that their kids couldn’t attend in-person school for more than a year. They resent that their businesses were forced to curtail their operations. They’re fed up with masks. And they’re sick and tired of being told what to do in the name of public health.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise that four of the Republicans with the best shot at taking over Newsom’s job vowed to do away with mandates for masks and COVID-19 vaccines at a recent debate.

Could they?

Probably, my colleague Phil Willon reports. Just as Newsom used his broad executive authority to implement all kinds of statewide rules, any successor would likely be able to dismantle them.

The state’s Emergency Services Act gives the governor broad authority to “make, amend and rescind” regulations, to suspend state laws, to reallocate state funds, and to take over hospitals, medical labs, hotels and other private property.

But there’s a catch: The governor can only take these sweeping actions if they make the health emergency better, not worse. A move that would arguably exacerbate the pandemic — such as dropping a vaccine or mask mandate — could be challenged in court, and a judge might well reject it, said Leslie Jacobs, director of the Capital Center for Law & Policy at the University of the Pacific McGeorge School of Law.

A new California governor may even go the way of Florida’s Ron DeSantis and Texas’ Greg Abbott and issue an executive order that forbids local authorities from implementing their own mandates. But that could be blocked by the state Legislature, where Democrats hold a supermajority of seats in both houses.

Technically, many of Newsom’s most reviled policies were ordered by California’s public health officer, Dr. Tomás J. Aragón. State law grants him the authority to respond to “any contagious, infectious or communicable disease” by taking “measures as are necessary” to “prevent its spread.” (The powers are so broad that the health department “may, if it considers it proper, take possession or control of the body of any living person.”)

A new governor would have the authority to replace Aragón and other public health leaders. Those nominations would go to the Legislature for confirmation, a step that gives Democrats a chance to block them. But if replacements are named while the Legislature is in recess — as it will be from mid-September to early January — they’ll be able to take the reins and undo Newsom-era orders before lawmakers have a chance to weigh in.

It’s also possible that California’s next public health officer could try to “modify or remove” a county health order, according to Santa Clara County Executive Jeffrey Smith. However, if that action weakened the health order, a court challenge would surely ensue, he said.

Recall backers get more attention, but there are plenty of voters who don’t want to see Newsom go. Sure, some of his actions were unpopular, but experts say they undoubtedly saved lives.

Lynn Lorenz of Newport Beach is one Californian who is willing to make that trade-off.

“A conservative Republican could do a lot of harm in California in a short period of time,” she wrote in a letter to the editor. “Most importantly would be decisions on mask mandates and distributing COVID-19 vaccinations. And what if more variants appear on the scene that are not stopped by the vaccinations we have now?”

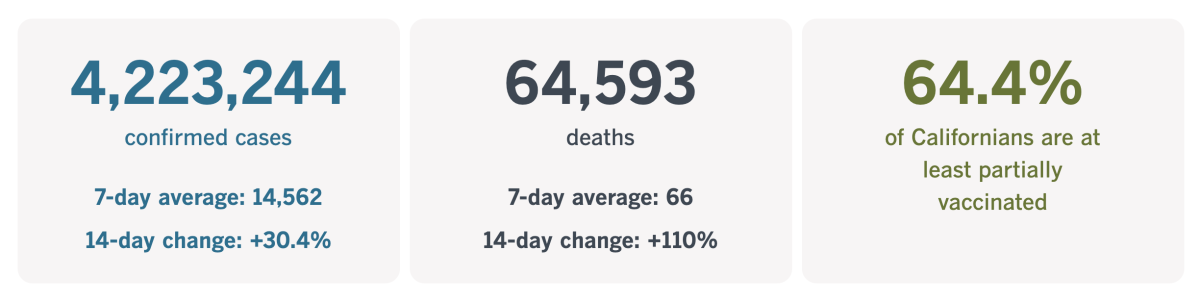

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 12:40 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The pandemic’s toll on working moms

After 14 years at a national accounting firm, Marian Millikan was on the verge of making partner. Then the pandemic came along in March 2020 — the height of tax season — and saddled her with a second full-time job: home-schooling her two elementary school-age children.

For about two months, she focused on her kids during the day, squeezed in Zoom meetings with clients when she could, and toiled at nights and on weekends to get her work done. Her husband helped, but the juggling act was exhausting. She described that time as “the hardest I’ve faced in my life.”

Her firm wasn’t willing or able to reduce her load. So Millikan, 37, made the agonizing decision to quit her job and walk away from a six-figure salary.

Now she’s a co-owner of a firm she started with several former colleagues and she “couldn’t be happier,” she says. She’s got more flexibility to split her time between work and family — but her paycheck took a big hit.

Multiply Millikan’s story by millions and you can see the rough outlines of the economic toll the pandemic has taken on working moms.

It’s not just a temporary loss of earnings, as my colleague Don Lee explains. This rebalancing of priorities is sure to reverse decades of progress when it comes to job security, career opportunities and pay equity.

Consider that 50 years ago, women made less than 60 cents for every $1 of median earnings for men, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2019, women’s pay reached a high of 82 cents to $1. When the figures for 2020 are released, experts expect to see a significant reversal.

Some working moms will never recover their COVID-19 losses. Even if they return to their pre-pandemic salaries, they’ll still feel the long-term effects of lost promotions and diminished retirement benefits.

This may come as something of a surprise, since telecommuting was long seen as a way to help working parents — particularly moms — free up time for family responsibilities. But over the last year and a half, working from home has morphed into living at work. (This working mom can personally attest to that.)

“They are getting extremely burned out, because in addition to trying to figure out how to do their job at home in a telework situation, they’re also providing care to their children. And that kind of multitasking is extremely hard,” said Misty Heggeness, a Census Bureau economist and mother of two middle schoolers who has been working from home herself.

The problem is widespread. A survey by the consulting firm Seramount found that roughly 1 in 3 moms in the workforce say they’ve scaled back their job duties or quit altogether — or intend to do so. All those moms add up to about 8 million workers, Lee reminds us.

One of them is Kelly Mann, 49, who until last year was a top manager at McGraw Hill who oversaw the rollout of remote teaching courseware in the mid-Atlantic region.

“It was sort of my dream job,” she said.

But like Millikan, Mann wound up sacrificing that dream job to the demands of home schooling. Her three daughters wouldn’t be able to succeed without her full-time attention. Her husband had to prioritize his job because the family depended on his salary, which was larger than hers.

With schools resuming on-campus instruction, Mann has returned to the workforce. Her new job pays one-fourth as much as her old one.

“I’m very much at the age where, when you leave a career at the level I was at, it’s going to be extremely challenging to reenter,” she said.

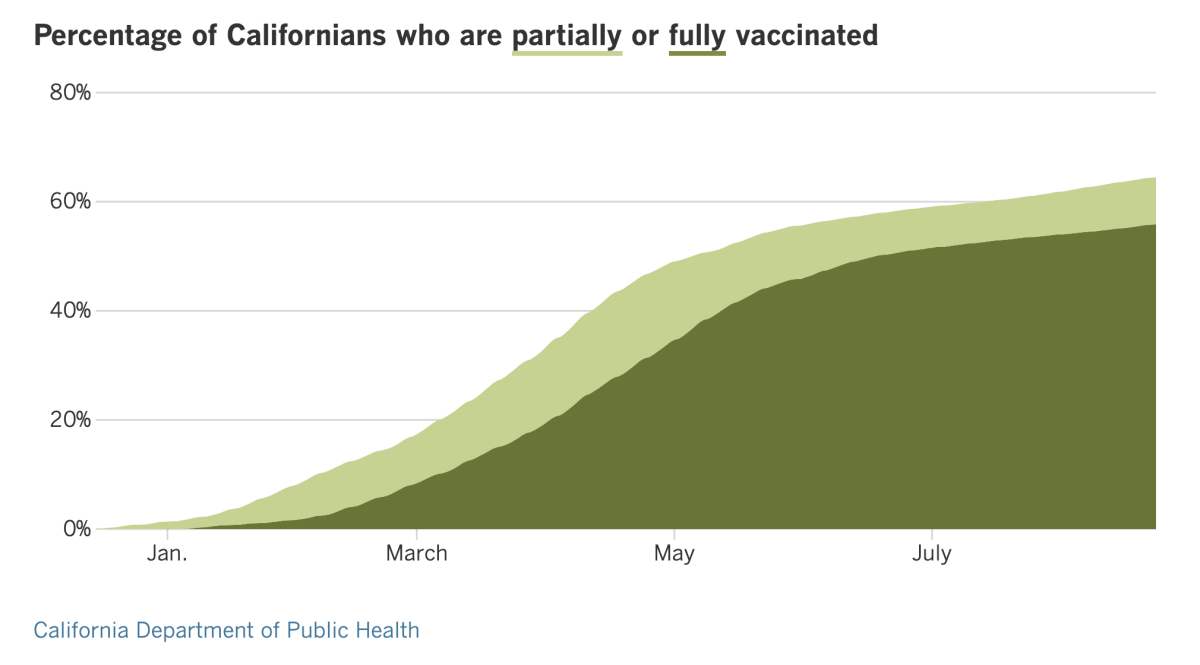

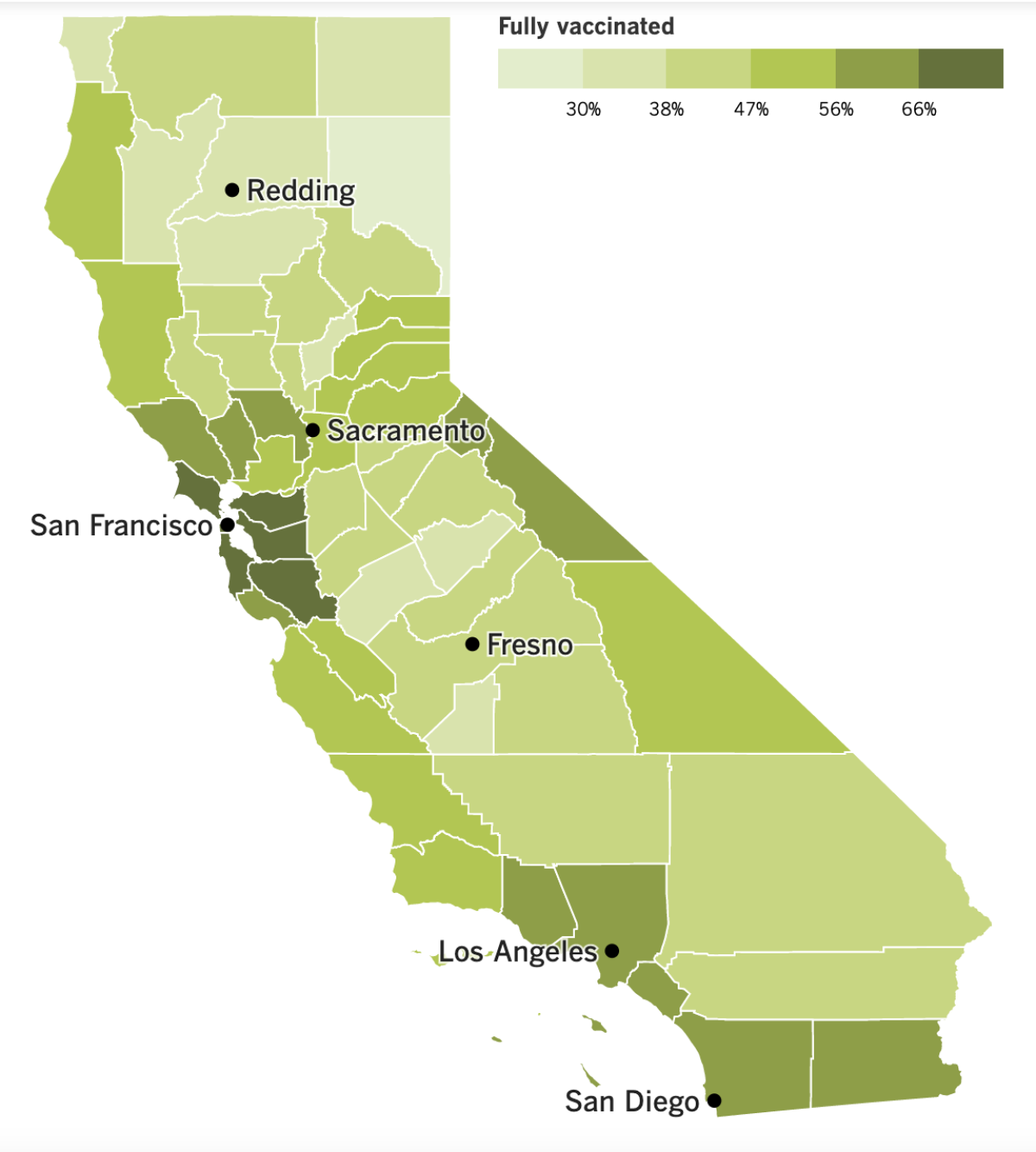

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

The big news this week (so far) is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s decision to grant full approval to Comirnaty, the COVID-19 vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech. Health officials hope Monday’s regulatory vote of confidence will encourage hesitant Americans to get immunized and prompt more employers to institute vaccine mandates.

Case in point: The Pentagon said COVID-19 inoculations would become mandatory for members of the military.

More than 200 million doses of the vaccine have been administered in the U.S., providing more than enough data for the FDA to determine that severe side effects are extremely rare. The data also showed that Comirnaty remained 97% effective against severe cases of COVID-19 six months after the second dose.

About 85 million Americans who are eligible for vaccination have yet to get the shots, and nearly one-third of them said they’d be more inclined to do so if a vaccine were fully approved, according to a recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

President Biden was eager to tout the FDA’s action, telling the vaccine-hesitant Americans that “the moment you’ve been waiting for is here.”

“As I’ve said before, this is a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” Biden added. “It’s a tragedy that’s preventable. People are dying and will die that don’t have to. So please, please, if you haven’t gotten your vaccination, do it now.”

A new survey by a human resources consulting firm found that American workers are warming up to vaccine mandates and other punitive measures for their unvaccinated colleagues. Forty-one percent of those polled said workers who remain unvaccinated should have to pay more for health insurance, and nearly two-thirds said the unvaccinated should not be rewarded with special dispensation to work from home.

The sooner people heed that message, the better. The U.S. is now averaging 738 COVID-19 deaths per day — and topping 1,000 on some days. Early last month, daily deaths averaged 189 per day, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In Los Angeles County, adults ages 18 to 49 are now registering a higher rate of coronavirus infections than people who are older or younger, according to data from the first week of August.

Among those who are vaccinated, the county tallied 144 infections for every 100,000 residents in the 18-to-49 age group. That compares with 60 cases per 100,000 people 17 and younger, and 74 cases per 100,000 people ages 50 and up.

The disparity is even more pronounced among the unvaccinated. In the first week of August, county officials recorded 449 infections for every 100,000 people ages 18 to 49. That compares with 233 cases per 100,000 younger people and 286 cases per 100,000 older people.

The state has released some promising figures about our overall progress in L.A. County: Only two additional COVID-19 patients were admitted to hospitals Monday, following four straight days of declines.

Earlier this month, hospitals were describing unsustainable conditions as they struggled to cope with a surge in cases fueled by the fast-spreading Delta variant. Now it seems we’re bending the curve. Still, the 1,724 hospitalized COVID-19 patients the county had on Monday is high enough to match the waning days of the fall-and-winter surge.

Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson and his wife, Jacqueline, remained in a Chicago hospital Monday to receive treatment for COVID-19.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, 79, is fully vaccinated — he got his first dose at a public event in January and urged others to do the same. But Jacqueline Jackson, 77, didn’t follow that advice and has not been vaccinated, according to a family spokesman.

The couple’s son Jonathan said his parents were resting comfortably and “responding positively to their treatments.”

A conservative radio talk show host from Nashville wasn’t as lucky. Phil Valentine, a vocal skeptic of the vaccines until he tested positive for a coronavirus infection, died of COVID-19 at the age of 61.

Valentine had told listeners he chose not to get vaccinated because he thought that even if he got COVID-19, it probably wouldn’t kill him. He changed his tune after he was admitted to a critical care unit, according to his brother, Mark Valentine.

“He regrets not being more adamant about getting the vaccine,” Mark Valentine said. “Look at the dadgum data.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Should I be worried about the Lambda variant?

The short answer: Not really.

The Lambda variant of the coronavirus was first spotted in California in April, the same month as Delta. At least 152 infections involving the Lambda variant have been documented in the state since. That may sound like a lot, but the number of confirmed Delta cases is nearly 70 times higher.

What’s more, the number of Lambda cases in California has been plummeting since the spring. In April, labs sequenced 88 Lambda specimens. They were followed by 43 in May, eight in June and just two in July, according to state officials.

Only one Lambda infection has been identified in L.A. County, and that was in June.

The variant was first identified in Peru, and “it has had massive spread in South America,” said Dr. Benjamin Pinsky, director of the Clinical Virology Laboratory at Stanford University. But its presence in the U.S. is so negligible that the CDC doesn’t even include it on its variant tracker.

The World Health Organization has designated Lambda a “variant of interest” and is watching it closely, said Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO’s technical lead for COVID-19.

Lambda has a mutation called L452Q that affects its spike protein, which the virus uses to enter cells. That mutation is similar to one called L452R that is found on the Delta variant. When the immune system of a vaccinated person encounters a strain with L452R, the effectiveness of certain antibodies is reduced by a factor of three, Pinsky said.

Even so, COVID-19 vaccines are doing their job by preventing infections that lead to severe illness and death.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.