The world didn’t end -- yet

- Share via

If you are reading this, then the world did not end today, as some thought it might. And chances are pretty good that the planet was not visited by a cataclysmic — pick one — earthquake, tsunami or volcanic eruption.

So much for another wacky end-of-the-world theory. The hypothesis that the world would be destroyed at the end of the 13th baktun cycle in the Maya calendar (which corresponds pretty closely with Dec. 21) was just plain wrong.

Nor, come to think of it, was the last much-publicized prophet of doom on target. That was Harold Camping, the Christian radio announcer who predicted that the rapture (and end of the world) would come on May 21, 2011. When that didn’t happen, he recalibrated the date as Oct. 21, 2011. He has since given up predicting disasters.

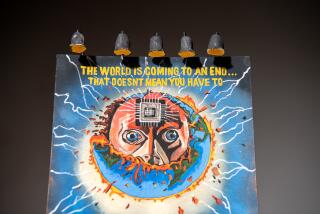

Humans have always been fascinated by the idea of the apocalypse. Sometimes we actually seem to believe in it; other times we’re just lapping up fantasies about dramatic destruction. In the 1999 doomsday action movie “End of Days,” for instance, the devil comes to Earth to claim his mortal bride and dominance over the world. But Arnold Schwarzenegger ends up (spoiler alert!) saving her — and the world — by impaling himself on a sword in a lofty Catholic cathedral that had begun to crumble around him.

What’s odd is that despite our apparent obsession with global catastrophe, we’re surprisingly reluctant to confront the complications of actual, documented threats to our planet. Science and observation seem to indicate that real planetary crises will come more quietly and slowly but just as sadly — and perhaps more so because by that time we will have had years, if not decades, of legitimate warning. The effects of climate change may not be as dramatic as the reappearance of Satan on Earth, but they are a lot more imminent. Scientists around the planet have urged political leaders to counter the threat with a variety of conservation measures, some of which we have pursued, some of which we’ve ignored. Meanwhile, global temperatures are already up, ice masses are melting, polar bears are being stranded on diminishing frozen habitats.

Nuclear annihilation, which would happen a lot faster and with a more cinematic bang, continues to be a possibility as more countries seek nuclear weapons or the material to make them. Reining in nuclear proliferation — and controlling those weapons that already exist — is complicated and controversial but surely worth fighting for.

It may be more fun to consider theatrical endgames and far-fetched predictions of doom, but really, shouldn’t we be concentrating instead on resolving the complex but scarily real scenarios facing us? At least then, Earthlings might stand a chance of surviving.