A retired teacher found some seahorses off Long Beach. Then he built a secret world for them

Rog Hanson emerges from the coastal waters, pulls a diving regulator out of his mouth and pushes a scuba mask down around his neck.

“Did you see her?” he says. “Did you see Bathsheba?”

On this quiet Wednesday morning, a paddle boarder glides silently through the surf off Long Beach. Two stick-legged whimbrels plunge their long curved beaks into the sand, hunting for crabs.

But Hanson, 68, is enchanted by what lies hidden beneath the water. Today he took a visitor on a tour of the secret world he built from palm fronds and pine branches at the bottom of the bay: his very own seahorse city.

The visitor confirms that she did see Bathsheba, an 11-inch-long orange Pacific seahorse, and a grin spreads across Hanson’s broad face.

“Isn’t she beautiful?” he says. “She’s our supermodel.”

If you get Hanson talking about his seahorses, he’ll tell you exactly how many times he’s seen them (997), who is dating whom, and describe their personalities with intimate familiarity. Bathsheba is stoic, Daphne a runner. Deep Blue is chill.

He will also tell you that getting to know these strange, almost mythical beings has profoundly affected his life.

“I swear, it has made me a better human being,” he says. “On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

Hanson is a retired schoolteacher, not a scientist, but experts say he probably has spent more time with Pacific seahorses, also known as Hippocampus ingens, than anyone on Earth.

“To my knowledge, he is the only person tracking ingens directly,” says Amanda Vincent, a professor at the University of British Columbia and director of the marine conservation group Project Seahorse. “Many people love seahorses, but Roger’s absorption with them is definitely distinctive. There’s a degree of warm obsession there, perhaps.”

Over the last three years, Hanson has made the two-hour trek from his home in Moreno Valley to the industrial shoreline of Long Beach to visit his “kids” about every five days. To avoid traffic, he often leaves at 2 a.m. and then sleeps in his car when he arrives.

He keeps three tanks of air and his scuba gear in the trunk of his 2009 Kia Rio. A toothbrush and a pair of pink leopard print reading glasses rest on the dash.

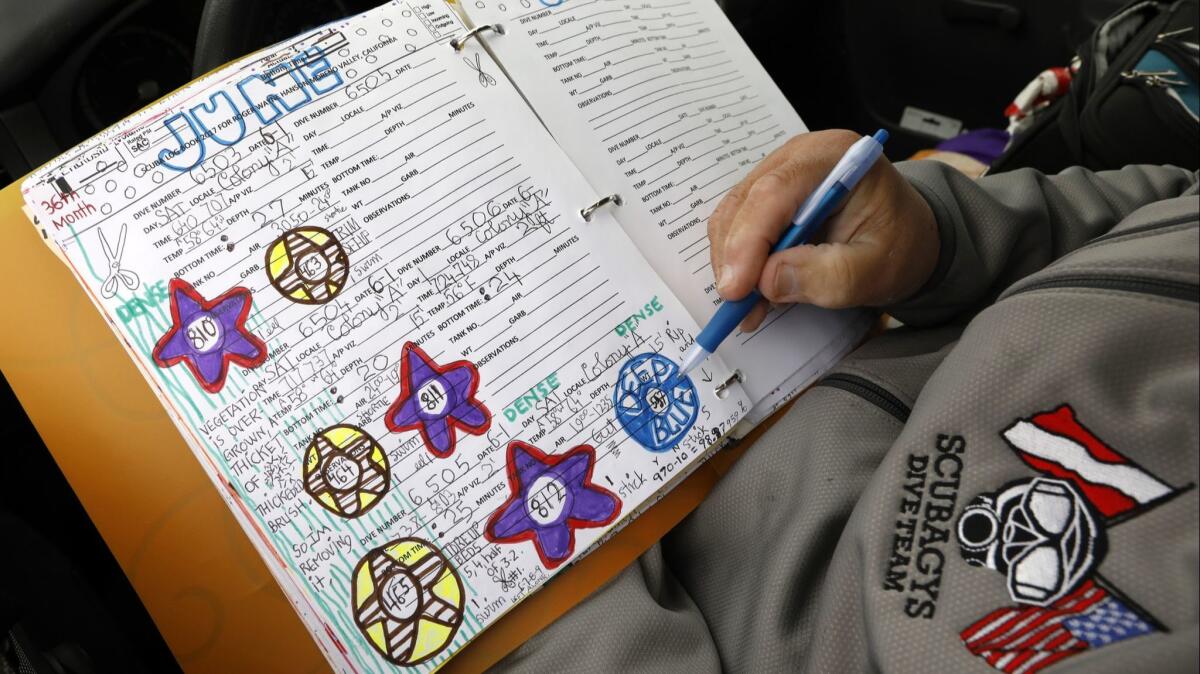

Hanson makes careful notes after all his dives in a colorful handmade log book he stores in a three-ring binder. On this Wednesday he dutifully records the water temperature (62 degrees), the length of the dive (58 minutes), the greatest depth (15 feet) and visibility (3 feet), as well as the precise location of each seahorse. His notes also include phase of the moon, the tidal currents and the strength of the UV rays.

“Scientists will tell you that sunlight is an important statistic to keep down,” he says.

He has given each of his four seahorses a unique logo that he draws with markers in his log book. Bathsheba’s is a purple star outlined in red, Daphne’s is a brown striped star in a yellow circle.

He’s learned that the seahorses don’t like it when he hovers nearby for too long. Now he limits his interactions with them to 15 to 30 seconds at a time.

“At first I bugged them too much,” he says. “I was the paparazzi swimming around.”

Hanson traces the origins of his seahorse story back nearly two decades to the early morning of Dec. 30, 2000.

He was diving solo off Shaw’s Cove in Laguna Beach when a slow-moving giant emerged from the abyss. It was a gray whale whose 40-foot frame cast Hanson in shadow.

The whale could have killed him with a flick of its tail, Hanson says, but he felt no fear. The two made eye contact and, as Hanson tells it, he felt the whale’s gaze peering directly into his soul.

It was all over in 10 seconds, but Hanson was altered. He had always wanted to live at the beach, but after this encounter, he vowed to make it happen. It took years —15, in fact — but he finally got a job as a special education teacher in the Long Beach public school system. He bought a van and parked it on Ocean Boulevard. He lived at the beach and dived every day for 3½ months before moving to Moreno Valley.

To amuse himself while he lived at the beach, he built an underwater city he called Littleville out of discarded toys he found at the bottom of the bay.

Hanson saw his first seahorse in January 2016 while checking on Littleville. It was bright orange, just 4.5 inches long, and Hanson, who had logged over a thousand dives in the area, knew it didn’t belong there.

The range of the Pacific seahorse is generally thought to extend from Peru to as far north as San Diego. This seahorse ended up about 100 miles north of that.

Scientists said the seahorse and others that joined her had probably ridden an unusual pulse of warm water up the coast, along with other animals generally found in southern waters.

“We were getting a lot of weird sightings in the fall of 2015,” says Sandy Trautwein, vice president of husbandry at the Aquarium of the Pacific. “There was a yellow-bellied sea snake, bluefin tuna, marlin, whale sharks — a lot of animals associated with warm water.”

Most of these animals eventually left after ocean temperatures returned to normal, but Hanson’s seahorses stayed.

That may be because Hanson had built them a home.

It happened like this: In June 2016 he watched in horror as more than 100 high school football players splashed in the shallow waters, right where his seahorses usually hung out.

“I thought, I gotta do something, I gotta do something,” he says.

“On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

— Rog Hanson

Then he remembered that, back in the Midwest where he grew up, he used to help the city park service make “fish cribs.” In early spring they would use brush and twigs to build what looked like a miniature log cabin with no roof on an ice-covered lake. When the ice melted, the cribs would fall to the bottom, creating a habitat for fish and other animals.

“So I said to myself, build them a city that’s deeper, where feet can’t get to it even at low tide,” Hanson says.

And he did.

By July 2016 two pairs of seahorses had moved into the new habitat. Daphne, the runner, was named after the nymph from Greek mythology who flees Apollo, Kenny’s name came from the proprietor of a local kayaking company. “Bathsheba” was inspired by a Bible story, and her mate, Deep Blue, named after a dive shop that has helped sponsor Hanson’s work since he launched his seahorse study.

He’s seen Kenny’s and Deep Blue’s bellies swell with pregnancy and noted how their partners check in on them daily, frequently standing sentinel nearby. He’s visited the fish at odd hours to see how their behavior changes from morning to night. And he mourned when Kenny disappeared in January. He still hasn’t come back. (A new member, CD Street, arrived June 29.)

“It feels like I’m reading a book, the book of their life, and I can’t put it down,” he says.

He’s also reached out to seahorse scientists across the globe to compare notes. “I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do,” he says.

Amanda Vincent, the director of Project Seahorse, says that seahorses spark an emotional reaction in almost everyone.

“Remember those books with three flaps where you can mix the head of a giraffe with the body of a snake and the tail of a monkey? That’s what we’ve got here,” she says. “They appeal to the sense of fancy and wonder in us.”

When Mark Showalter, a planetary astronomer at the SETI Institute, recently discovered a moon orbiting Neptune, he named it Hippocamp in part because of his love of seahorses.

“I’ve seen them in the wild and they are marvelously strange and interesting,” he says. “It’s a fish, but it doesn’t look anything like a fish.”

Pacific seahorses are among the largest members of the seahorse family. Males can grow up to 14 inches long, while females generally top out at about 11. They come in a variety of colors, including orange, maroon, brown and yellow. They are talented camouflagers that can alter the color of their exoskeleton to blend into their environment.

“I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do.”

But perhaps their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are the only known species in the animal kingdom to exhibit a true male pregnancy. Females deposit up to 1,500 eggs in the male’s pouch. The males incubate the eggs, providing nutrition and oxygen for the growing embryos. When the larval seahorses are ready to be released, he goes into labor — scientists call it “jackknifing” — pushing his trunk toward his tail.

After three years of observation, Hanson has collected new evidence about seahorse mating practices. His research suggests that although most seahorses are monogamous, a female will mate with two males if there are no other female seahorses around.

He also found that males, who are in an almost constant state of pregnancy, tend to stick to an area about the size of a king-size mattress, while the females roam up to 150 feet from their home during a typical day.

Eventually, he may be able to help scientists answer another long-standing question: What is the lifespan of Pacific seahorses in the wild? Some researchers say about five years; others think it could be up to 12.

“It will be interesting to see what Roger finds out,” Vincent says.

In June 2017, about one year after Hanson began formally tracking the seahorses, he took on a partner: a young scuba instructor named Ashley Arnold.

Arnold, who has short red hair and a jocular vibe, is a former Army staff sergeant who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. She learned to dive as part of a program the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs hospital offered to female veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma. Arnold suffered from both. Diving became her salvation.

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water,” she says. “It’s like, ‘What was I concerned about?’ You forget about everything else. Nothing else matters.”

She used her GI Bill to pay for a scuba instructor course and to set up her own business. Now, she finds that if she dives at least twice a week and has a dog, she does not need to take medication.

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water.”

— Ashley Arnold

“That’s a pretty big statement in my opinion,” she says.

Arnold and Hanson met in June 2016 on a dive trip to Catalina. Hanson mentioned his seahorses. Arnold was intrigued, but still lived in Salt Lake City.

One year later, Arnold moved to Huntington Beach and gave Hanson a call.

“I said, ‘Hey Roger, let’s chat. Any chance I could join you at the seahorses you talked about?’” she says. “And he decided I was acceptable.”

Now, Arnold and her boyfriend, Jake Fitzgerald, check in on the seahorses about once a week and help Roger rebuild the city he created for them.

“We call them our kids because we love them so much,” Arnold says.

Hanson and Arnold are very protective of their seahorse family. They tell visitors to remove GPS tags from their photos. They swear them to secrecy.

There is little chance anyone would find Hanson’s seahorses without a guide. Also, diving in these waters off Long Beach can be a challenge.

The water is shallow. It’s hard to get your buoyancy right. A misplaced flipper kick can stir up blinding sand and silt.

But if Hanson wants to show you his underwater world, nothing will stop him. He will hold you firmly by the hand and guide you down to the forest he built at the bottom of the bay.

He will use a plastic tent stake, jabbing it into the bottom to propel himself — and you holding on — across the ocean floor. When he spots a seahorse he will use the stake as a pointer. Through the murky water you strain to see. Then it appears.

Orange and rigid. Thin snout. Bony plates. Stripes down the torso. Totally still.

And if you’ve never seen a seahorse in the wild before, you will feel honored and awed, as if you’ve just seen a unicorn beneath the sea.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.