How a plan to ration water in Southern California will work

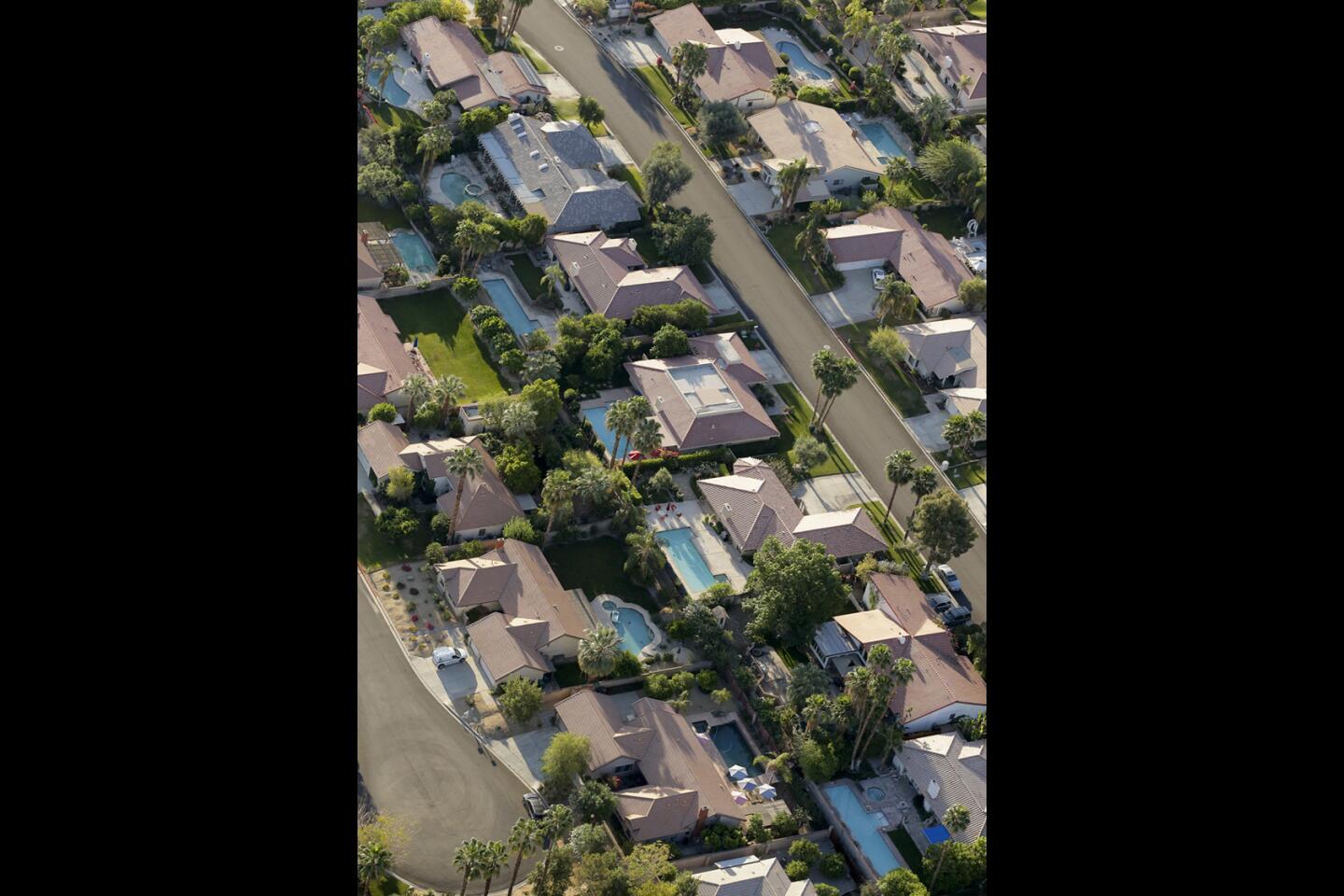

Southern California’s water wholesaler is planning to wield its powerful hammer to force more urban conservation this year by cutting water deliveries.

Faced with dwindling regional reserves and a fourth year of drought, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California is expected to vote next week to ration imported water that it supplies to 26 Southland water districts and cities, something the agency has done only twice before.

The cuts, which would take effect July 1, were in the works well before Gov. Jerry Brown imposed a 25% mandatory restriction on urban water use last week. But they are expected to provide a powerful incentive for local agencies to curb demand and help meet the governor’s conservation goals.

RELATED: From steak to mangoes, here are some water-hogging foods

Local agencies that need more water than the MWD allocation will be required to pay punitive surcharges of up to $2,960 an acre-foot for the extra deliveries.

For purchases well beyond the allocation, that would increase the price of fully treated MWD water by roughly four times.

The MWD board, made up of 37 representatives of the agency’s member districts, will decide the size of the cutback, which could range from 10% to 20%, or 200,000 to 400,000 acre-feet less than MWD typically delivers. An acre-foot of water is enough to supply two households for one year.

The effects will vary from area to area. Cities that have already been conserving, such as Los Angeles, will probably feel fewer impacts. In areas that have been slow to conserve, water districts will have to strengthen restrictions and boost local rates to avoid financial penalties the MWD will impose on excess demand.

Metropolitan, which imports water from Northern California and the Colorado River, last rationed deliveries in 2009 and 2010, during the previous drought. Then, local districts responded so well that none had to buy high-priced water.

But because continuing conservation efforts have lowered water use in most parts of the urban Southland in recent years, districts may find it harder to stay within their allocations this time.

“The question is how much more can people squeeze out in conservation than they’re already doing,” said Dennis Cushman, assistant general manager of the San Diego County Water Authority.

The current drought is one of the most punishing in modern history. Irrigation deliveries have been slashed, forcing growers to idle more than 400,000 acres of cropland last year. Groundwater levels in some parts of the San Joaquin Valley have plunged to record lows as farmers drill more and deeper wells. Some small communities dependent on local sources have run out of water.

The levels of major reservoirs in Northern California are higher than they were a year ago. But the mountain snowpack that in a normal year provides the state with about a third of its water supply hit a record low for April 1.

Last week, Brown used a snowless Sierra Nevada meadow as the backdrop to announce the first statewide mandatory restrictions on urban use in California history.

Metropolitan customarily provides about half the Southland’s water supplies. The agency began the drought in 2012 with record amounts of water reserves stashed in groundwater banks and regional reservoirs. But as the drought lingered, the water wholesaler has drawn heavily from its backup supplies to meet regional demands. Some customers have raised concerns that the MWD is depleting its stockpile too quickly.

“It’s a big number,” Cushman said of the 1.1 million acre-feet Metropolitan pulled out of storage in 2014 — enough water to supply 2.2 million households for a year.

That left 1.2 million acre-feet in storage, down from a peak of 2.7 million acre-feet at the end of 2012. The MWD also maintains a supply of 640,000 acre-feet that it would only tap in an emergency, such as an earthquake that damages the state’s major aqueducts.

“I get the concern about our storage levels,” said Jeffrey Kightlinger, Metropolitan’s general manager. “We are pulling them down. [But] it is what they’re there for. It is for dealing with drought.”

Reducing deliveries will slow, but not stop, the drop in reserves. Kightlinger said Diamond Valley Lake, the agency’s big Riverside County reservoir, will probably fall this year to its lowest level since it was filled after construction more than a decade ago.

Still, Kightlinger said, “With prudent management, we’re good for another two, three years of drought.” If the drought persists beyond that, he said, his agency would have to make more draconian cuts.

This year, the MWD is getting more deliveries from one of its two main sources, the California State Water Project, than in 2014 — 20% of requested amounts compared with 5% last year. It will receive full Colorado River deliveries and water from the Palo Verde Irrigation District in Riverside and Imperial counties under a long-term program in which Palo Verde growers are paid to fallow cropland and send the conserved supplies to Metropolitan.

The MWD board authorized its staff to spend up to $71 million to buy as much as 100,000 acre-feet from farmers with senior water rights in Northern California, although Kightlinger said he doubted that much water would be available.

The agency is also pouring roughly $100 million into its turf rebate program, which pays commercial and residential water users to replace grass with drought-tolerant plantings.

“Now we’ll take the next step,” said Rob Hunter, general manager of the Municipal Water District of Orange County, which buys supplies from the MWD. He added that there is general support for the cuts among the MWD’s member agencies. “I think everybody believes there’s a need for allocation.”

Martin Adams, senior assistant general manager of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, said that if present trends continue, the city this summer will have reduced its water use by 10% since late 2013, putting it in a decent position to weather a cut from the MWD.

“The word’s gotten out and the L.A. populace is really responding well,” he said. “We hope that … is enough to get us through whatever [the MWD] does.”

Twitter: @boxall

ALSO:

Gov. Brown’s drought plan goes easy on agriculture

Drought will prove a formidable opponent in Brown’s final term

8 images that explain how bad the California drought has become