News Analysis: Chief Justice Roberts has a Clarence Thomas problem

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. has always said he believes ethical standards at the Supreme Court should depend not on clear and binding rules, but on the “good judgment” of the nine justices.

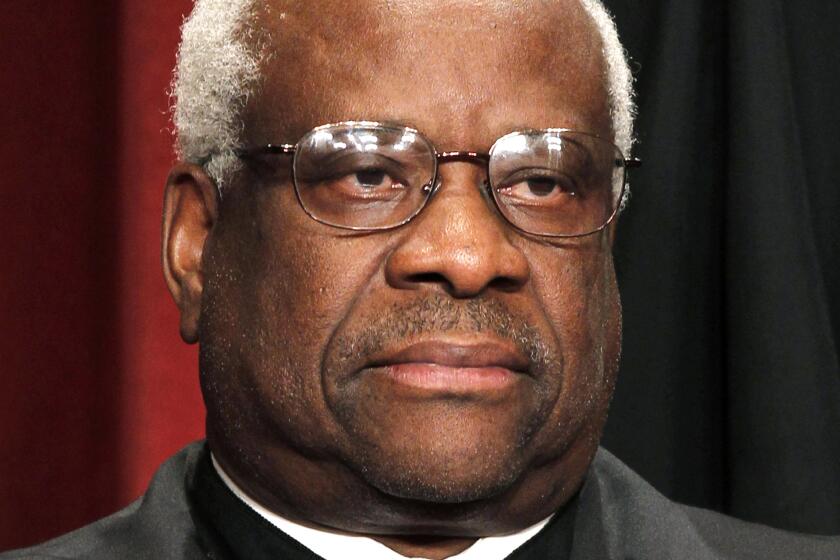

That assertion is being tested as never before by Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife, Virginia “Ginni” Thomas, whose willingness to accept gifts has turned an uncomfortable spotlight on Roberts and the high court.

Roberts has held himself out as the model of an independent, nonpartisan jurist during his 17-year tenure.

He has avoided political or ideological gatherings, including the Federalist Society, the favorite forum for conservative judges and lawyers. In his personal and public behavior, he appears to follow the “Code of Conduct for U.S. Judges” — first adopted in 1973 — which states that federal judges “should act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.”

A 2004 Los Angeles Times report disclosed gifts to Justice Thomas from rich Texan Harlan Crow. In response, Thomas stopped disclosing them.

But equally important to Roberts has been maintaining the strict independence of the Supreme Court. And with each new revelation about Thomas, those ideals are becoming harder to reconcile.

He said that though the judicial code provides “guidance,” the justices are not bound by it. Roberts so far has rebuffed calls for the court to create its own code of ethics and questioned whether Congress has the constitutional authority to do so.

Last week he declined an invitation from the Senate Judiciary Committee to speak about possible ethics reforms for the high court, citing the “separation of powers” between the government’s judicial and legislative branches.

In Roberts’ view, ethics begin and end with the conscience of each individual justice.

“At the end of the day, no compilation of ethical rules can guarantee integrity,” he wrote in 2011. “Judges must exercise both constant vigilance and good judgment to fulfill the obligations they have all taken since the beginning of the republic.”

But although such well-intended and high-minded ideals may have served the court in the past, some legal experts fault Roberts for not doing more.

“The court should police itself, and it has the tools to do it,” said Amanda Frost, a University of Virginia law professor. “He could take the lead and should take the lead, but he hasn’t.”

New York University law professor Stephen Gillers agreed the court needs a binding ethics code.

“We used to rely on respect for norms and self-restraint — on officials’ treating our institutions, including the court, with respect and care, [even] when there is no rule,” Gillers said. “The lesson of the Trump years is that this reliance is inadequate.”

One obstacle may well be Roberts’ colleagues on the bench. It is not clear whether Roberts would have the support of the other justices to impose a stricter ethics code, even if he wanted one.

On the right, the recent uproar over Thomas and his wife is seen as politically motivated, not ethics. It’s a view probably shared by some of the court’s conservatives.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) on Tuesday called it “an unseemly effort by the Democratic left to destroy the legitimacy of the Roberts Court... There’s a very selective outrage here.”

Conservatives note that poor judgment that undercuts the appearance of impartiality is not limited to one side of the political spectrum.

For much of her career, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a headline speaker at annual events for the NOW Legal Defense Fund, even though the group regularly filed friend-of-the-court briefs on women’s rights issues.

In the summer of 2016 when Donald Trump was running as the Republican nominee for president, she criticized him in a series of interviews.

“He’s a faker... and really has an ego. How has he gotten away with not turning over his tax return?” she asked, a question that would later come to the high court.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) said the ethics issue should not be partisan. He said it was troubling that judges, federal employees and members of Congress are bound by strict rules, and they can be fined or punished for violations, but the Supreme Court has exempted itself.

“The highest court in the land should not have the lowest ethical standards. That reality is driving a crisis in public confidence in the Supreme Court,” he said.

After declining to testify before the Senate, Roberts instead sent a general “Statement on Ethics Principles and Practices” that was signed by all nine justices.

It “reaffirms” their commitment to abide by the ban on most outside income, except for teaching and writing books, and the requirement to disclose gifts. It noted the recent “clarification on the scope of the ‘personal hospitality’ exemption” to the disclosure rule for gifts.

That was the only reference to the recent revelations by ProPublica that Thomas and his wife had for many years taken free and undisclosed vacations aboard a private jet and yacht with Harlan Crow, a Texas real estate billionaire and Republican donor.

It turned out Thomas had adopted a conveniently narrow interpretation of the federal ethics law. It said judges, justices and federal employees must disclose the source and value of significant gifts they received, but not for “any food, lodging or entertainment received as personal hospitality.”

Thomas explained that early in his career, he had sought guidance from unnamed colleagues and concluded that free international travel on private jets and yachts was covered by the exemption for “food, lodging or entertainment.” In March, the Judicial Conference issued new guidance to make clear that such travel is not shielded from disclosure.

Thomas described Crow and his wife as “among our dearest friends.” However, Crow said he introduced himself to the conservative justice in 1996, five years after he had ascended to the high court.

Crow also figured in an earlier controversy that involved Thomas, his wife and the Supreme Court.

In 2009, when tea party groups were fighting the Obama administration, Ginni Thomas launched a group called Liberty Central. It was later revealed that Crow funded it with a $500,000 contribution.

A year later, as conservatives mounted a legal challenge to Obamacare, Liberty Central’s website posted an attack on the “unconstitutional” law.

“With the U.S. Constitution on our side and the hearts and minds of the American people with us, freedom will prevail,” the group said.

When the Supreme Court agreed in 2011 to rule on the law’s constitutionality, Common Cause said Thomas should recuse himself, citing his wife’s public role in fighting against the healthcare legislation.

At the same time, some Republicans argued Justice Elena Kagan should step aside because she was President Obama’s solicitor general when the healthcare law was adopted.

Federal law leaves such questions of recusal in the hands of individual justices, saying a justice “shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

Both justices refused to withdraw, and in his year-end report, the chief justice said he had “complete confidence in the capability of my colleagues” to decide for themselves whether to withdraw from a case.

More recently, Thomas has faced calls to recuse himself because of his wife’s role in urging the Trump White House to fight the 2020 election won by Joe Biden.

“Help This Great President stand firm, Mark !!!” she wrote in an email to then-White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. “The majority knows Biden and the Left is attempting the greatest Heist of our History.”

Thomas did not step aside from deciding the Republican appeals that followed Trump’s loss, or challenges to documents sought by the House Jan. 6 Committee that investigated the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Out of office, Trump sued to block the Library of Congress from turning over White House documents to the House committee. Some speculated they could include more messages from Ginni Thomas.

Trump lost in the lower courts, and the Supreme Court turned down his appeal with only one dissent. It came from Clarence Thomas.

Last week, however, the court said nothing would change on recusals.

“Individual Justices, rather than the court, decide recusal issues,” they said in the statement sent to Sen. Durbin. “If the full court or any subset of the court were to review the recusal decisions of individual justices, it would create an undesirable situation in which the court could affect the outcome of a case by selecting who among its members may participate.”

The revelations about Thomas’ acceptance of expensive gifts, private jet travel, luxury vacations, and most recently, tuition payments at his grandnephew’s private boarding school have spawned more news stories alleging supposed ethical lapses by other justices.

The chief justice’s wife, Jane, stepped away from her law practice to avoid potential conflicts with her husband’s work and instead took a job as a recruiter placing attorneys in law firm jobs. She was criticized because those law firms in turn have cases that go to the high court.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch faced criticism because he and three co-owners sold their fishing cabin in Colorado for less than the asking price shortly after he moved to Washington. He disclosed the ownership sale as required, but he did not name the buyer, a prominent law partner who has said he did not know Gorsuch or that he was a part-owner when he made his offer.

Contrary to these stories, the broader problem facing the court is not corruption, but the justices appearing as partisans and ideologues.

In past decades, the justices carefully avoided public appearances that would undermine what the code of conduct described as the appearance of impartiality.

That was the rule across the ideological spectrum, from conservative Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist to moderates like Anthony M. Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor and liberals like John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter or William J. Brennan Jr.

But most of today’s justices no longer feel bound by that rule of restraint. Having been nominated and confirmed in highly partisan battles, they appear willing to show their allegiance to their supporters.

The court’s conservative justices go to the Federalist Society’s annual banquet to be applauded and celebrated, while most of the liberals — but not Kagan — appear at the meetings of the progressive American Constitution Society.

Not long after being confirmed by the Republican-controlled Senate, Justices Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett journeyed to Kentucky to appear with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell.

“My goal today is to convince you that this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks,” Barrett said, even though her appearance may have undercut the message.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.