Disabled voters in Wisconsin win over help returning ballots

- Share via

MADISON, Wis. — Trudy Le Beau has voted in every major election since she turned 18 — a half-century of civic participation that has gotten increasingly difficult as her multiple sclerosis progressed. Now, with no use of her arms or legs, the Wisconsin woman relies on her husband to help her fill out and return a ballot.

This year, it seemed for the first time that the 68-year-old would have to choose between her physical health and voting.

After the Wisconsin Supreme Court outlawed ballot drop boxes in July, the state’s top election official cited a state law that said voters had to place their own absentee ballots in the mail or return them to clerks in person.

“I certainly don’t want to send my husband to jail because he put my ballot in the mailbox,” Le Beau said. “I would have to find some way of putting my ballot in my teeth and carrying it to the clerk’s office.”

Fortunately for Le Beau, she and other Wisconsin voters with disabilities can get the help they need to return their ballots this November after a federal judge last month ruled that the Voting Rights Act, which allows for voter assistance, trumps state law.

In other states, however, battles continue over ballot assistance and other voting laws that harm voters with disabilities. As voters push back, challenges have arisen in the last two years to laws and practices in at least eight states that make it difficult or impossible for people with certain disabilities to vote.

A federal judge in June struck down voter assistance restrictions in sweeping changes to election laws passed by Texas Republicans last year that in part limited the help that voters with disabilities or limited English proficiency could get. Under the law, a voter could only receive assistance reading or marking a ballot, not returning one.

Call it the ‘I don’t know’ election in the fight for Congress. Republicans still have advantages, but Democrats appear energized in the post-Roe environment.

In July in North Carolina, a federal judge blocked state laws that limited people with disabilities to receiving ballot assistance only from a close relative or legal guardian. Restrictions on ballot assistance still stand in several other states, including Kansas, Iowa, Kentucky and Missouri. In Missouri, an ongoing lawsuit challenges a 1977 state law that says no one can assist more than one voter per election.

A Kansas judge in April dismissed parts of a lawsuit challenging voter assistance restrictions, saying the state’s interest in preventing voter fraud outweighed concerns about voters who may not get the assistance they need.

But such anti-fraud measures — a major push by Republicans since former President Trump’s false claims of a stolen election in 2020 — don’t affect everyone equally.

“Voting restrictions aimed at the general public can have a disparate impact on people with disabilities,” said Jess Davidson, communications director for the American Assn. of People With Disabilities.

Voters and state agencies in Alaska, New York and Alabama have also raised challenges to absentee voting programs that don’t provide accessible ballots for people with visual impairments or disabilities that make it difficult to fill out a print ballot privately. Advocacy groups in New York reached a settlement in April that requires the state elections board to create a program for disabled voters to fill out and print accessible online ballots.

Wisconsin voters with disabilities expressed frustration at having to fight for equal voting rights when federal law already lays out specific provisions for accessibility.

“This whole issue was absolutely ridiculous to start out with. It shouldn’t matter if you need assistance returning your ballot,” said Stacy Ellingen.

Ellingen, 37, has athetoid spastic cerebral palsy because of complications at birth. She lives in Oshkosh, Wisc., and with no accessible transportation options, absentee voting is the only way she can cast a ballot. She said if it weren’t for the ruling handed down two weeks ago, she wouldn’t have been able to vote this fall.

“I’m not going to risk having caregivers get in trouble for putting my ballot in the mailbox. Especially when we have such a caregiver shortage,” she said.

Republican lawmakers have yet to offer any resistance to the Wisconsin ruling. But Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, a law firm that frequently litigates for conservative causes, raised concern that the ruling could perpetuate fraud. They unsuccessfully pressed the Wisconsin Elections Commission to require anyone returning a ballot on someone else’s behalf to sign a statement saying the voter has a disability and requires assistance.

Statewide offices, congressional seats, L.A. mayor, propositions — including on abortion, sports betting and taxes — are up in the November election.

Davidson, of the American Assn. of People With Disabilities, called the argument that voter assistance will lead to fraud “simply inaccurate, and motivated by anti-democratic interests.”

Martha Chambers was paralyzed in a horseback riding accident 27 years ago. She uses her mouth to hold pens, paintbrushes and mouth sticks, which allow her to use a computer. Chambers also relies on a power wheelchair to get around.

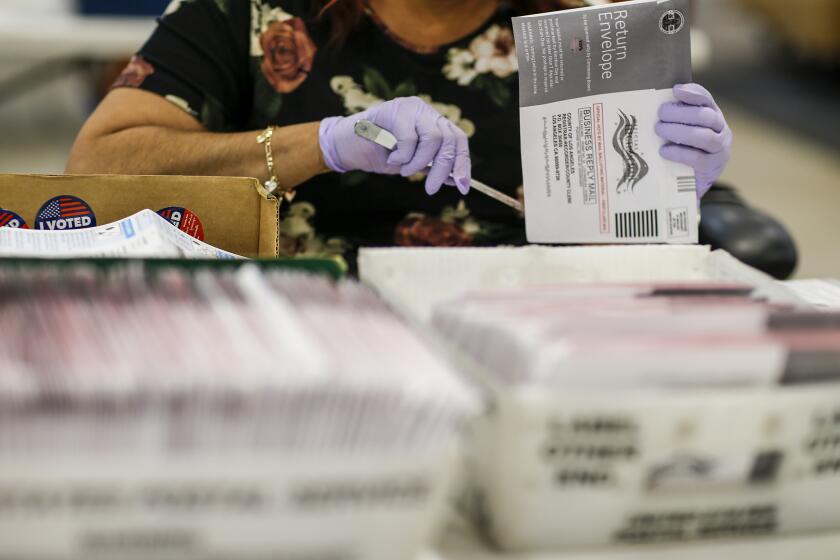

Because she can’t use her arms, she’s unable to return her own ballot to a mailbox or polling location. A caregiver returned her ballot in Wisconsin’s August primary, and Chambers said she joined the lawsuit so it wouldn’t be illegal in future elections for caregivers to give such help.

“Why did we even have to go through all of this to begin with? Our lives are difficult enough with the challenges that we have on a daily basis,” she said.

AP reporters Summer Ballentine in Jefferson City, Mo., and Heather Hollingsworth, in Kansas City, Kansas, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.