Sanders camp is pulled in different directions as defeat inches closer

- Share via

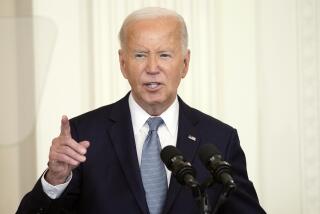

WASHINGTON — As Bernie Sanders heads into a crucial moment — the Vermont senator trails Joe Biden in the delegate count and is far behind in polls of Tuesday’s main battleground in Michigan — his campaign is being pulled in conflicting directions that have left even some senior officials puzzled.

“There have been some big tensions,” said a high-ranking campaign official, who was among several inside the Sanders operation who agreed to speak frankly about its internal workings under condition of anonymity.

The nerve center of the Sanders operation is a small collection of old-guard stalwarts and energetic newcomers. Jane Sanders, the senator’s wife, and Jeff Weaver, his longtime consigliere and 2016 presidential campaign manager, compete for the senator’s attention with current campaign manager Faiz Shakir and deputy campaign manager Ari Rabin-Havt, who may spend more time with Sanders than any other staffer.

The conflicting opinions within the top ranks come amid mixed signals the Sanders camp sent after the senator’s disappointing losses on Super Tuesday.

Sanders sought to reassure skeptical mainstream Democrats that they have a home in his crusade by launching an advertising blitz starring old audio clips of Barack Obama lauding the Vermont senator.

Yet other moves were less comforting to those same voters. Sanders and his surrogates lashed out at the media, attacked the Democratic “establishment” and named as campaign co-chair in Michigan a congresswoman who last month encouraged an audience to boo former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Instances like that reflect a campaign whose inner circle looks very different than it did in 2016, but which still confronts the same key challenge — persuading a stubborn senator to take steps to broaden his appeal. In some ways, that challenge has grown, after Sanders replaced the senior leadership team from the last campaign, which had deep experience in presidential politics, with one much newer to the game.

The campaign did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In interviews, campaign aides and those close to the campaign repeatedly pointed to Sanders’ failure to make inroads with African American voters — a shortcoming that threatens to once again sink his campaign. The lack of progress on that front reflected weakness in the senator’s inner circle, as well as the senator’s reluctance to take advice, some said.

“We needed to do more,” the high-ranking official said. “We needed a better strategy.”

A veteran progressive strategist with knowledge of the campaign’s mechanics was more blunt, pointing to the lack of campaign experience of some of Sanders’ top people: “These are people who have never run a city council race,” the strategist said.

The installation of Shakir as campaign manager early last year marked a powerful acknowledgment by Sanders of a need to diversify his base and message. Shakir, a former political director of the American Civil Liberties Union and aide to former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada, is Pakistani American and the first Muslim to run a major presidential campaign. Rabin-Havt came with his own Capitol Hill background, a seasoned fighter from Reid’s operation whose resume includes work in progressive advocacy groups.

The two stalwart progressives may be more connected to the voters who form Sanders’ base than was Tad Devine, the longtime Democratic messaging pro who helped Sanders engineer his insurgent rise in 2016. Campaign insiders credit Shakir with developing the strategy that helped resuscitate the Sanders campaign after the candidate suffered a heart attack last fall — one that highlighted the endorsement of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and other progressive favorites in the House.

Backing from Ocasio-Cortez and her allies in the Squad — the group of young, female members of Congress who have set the agenda for the party’s left, helped the senator make big gains among Latino voters, which powered his decisive victory in Nevada last month and pushed him into the lead in delegate-rich California.

But several campaign officials said that much of the credit for that success goes to behind-the-scenes work by a veteran Latino operative and union organizer named Chuck Rocha, who had the contacts and organizing experience to build a highly effective outreach operation but who is relatively little known outside the campaign.

“We have no Chuck Rocha in the African American community,” said one campaign official. “We need several.”

In part, the absence of such seasoned operatives stems from Sanders’ inclination to hire fresh faces who have credibility with grass-roots organizations rather than people with deep roots within the mainstream of the Democratic Party. The campaign’s political director, for example, was formerly the director of the New Jersey Working Families Alliance.

The relative scarcity of longtime Democratic operatives is a point of pride for the outsider campaign. But it also has left the campaign adrift at times when message discipline and focus are urgently needed.

In the days leading up to Super Tuesday, for example, Sanders made statements that defended some of the policies of the late Cuban dictator Fidel Castro — language that unnerved many Democratic voters — and aggressively aligned his agenda with that of the Squad. Those moves may have been strategic errors, campaign officials said, but no one within the organization was in a position to talk the candidate out of them.

“The Squad helped us with younger voters, but it is not popular in the African American community, and it is not popular in the Midwest,” said a campaign official. “You could not get the Squad elected to be the Democratic nominee. The party is just not there. The things they are doing rub some people the wrong way.”

That official pointed to the booing of Hillary Clinton by Michigan Rep. Rashida Tlaib and Ocasio-Cortez’s comments on abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement as examples of steps that undermined Sanders’ hope of broadening his movement.

Others are frustrated by the influence over the campaign of Jane Sanders, who has a tendency to second-guess staff decisions — a perennial problem that has vexed other campaigns.

The “Not me. Us” slogan of the campaign is not one that it always practices internally. The lack of operatives with decades of experience has freed Sanders to run things the way he long has — based on his gut, with input from his wife. It is why Bernie Sanders on the stump in 2020 sounds almost exactly like Bernie Sanders on the stump in 2016. Or 1990, for that matter.

The one aide who has an ability to sometimes change Sanders’ mind, campaign aides said, is Weaver, who has worked with Sanders for more than 30 years. A feisty strategist who has been crusading alongside Sanders since his ill-fated 1986 run for governor of Vermont, Weaver talks on the phone frequently with the senator and can channel him better than any aide or surrogate.

Like Sanders, Weaver is eccentric and unyielding. He has done every job for the senator from sign holder, to driver, to chief of staff in his Senate office.

When Weaver took a break from working for Sanders on Capitol Hill, he ran a comic book store. During the 2016 campaign, Weaver and Devine worked comfortably as partners, and their interactions with the candidate were not complicated by an experience imbalance; they had weathered nearly as many high-stakes political battles over the years as Sanders.

Devine’s firm parted ways with the Sanders campaign just before the senator launched his 2020 bid. Weaver was given a more limited role operationally, as the campaign moved to broaden its appeal to women and minorities with a newer generation of leadership.

The end result is an operation where the senator’s instincts often win out over message discipline. And those instincts often take him in a direction that has not expanded his base of support and has once again left him on the brink of defeat.

“Who can change Bernie’s behavior and strategy?” said Adam Jentleson, a former Harry Reid aide who backed Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

“Nothing changed. There were aborted attempts to do so. But basically he ran the same campaign he ran in 2016. It doesn’t make sense to run for the nomination of a party by running against the people in the party.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.