- Share via

DUBUQUE, Iowa — Jason Greer will never forget what it was like to be a black teenager in Dubuque when it tried to bring about racial healing after several hate crimes in the 1990s. The experience scarred him for life.

His father, Jerome Greer, had moved the family here from St. Louis after he was recruited to become Dubuque’s first black school principal in 1991.

Vandals burned crosses to show their disapproval, one within eyeshot of Jerome’s school.

Dubuque was a nearly all-white city with a long-running reputation for not welcoming blacks. Jason said white children ran away when they saw him, and he was constantly targeted with racial slurs. He rarely strayed far from home.

“I was called the N-word so often that my running joke was I should change my name to the N-word to make it easier for people,” says Jason, now 45.

Dubuque has tried repeatedly to make itself a welcoming place for people of color, and it has made strides over the years. But its efforts to eliminate hate and discrimination show how hard it is to confront racism — and how much is at stake for people of color who live in communities struggling to make amends for bigotry.

The nearly all-white city of Dubuque, Iowa is trying to shed its racist reputation. (Jackeline Luna and Maggie Beidelman / Los Angeles Times.

On Monday night, Iowa will cast the first votes of the 2020 presidential campaign. Every four years, the state and its voters face widespread criticism that the place is too white, too rural and its residents too parochial to play such an outsized role. Iowa’s agenda, detractors say, doesn’t reflect what’s important to people of color.

But issues at play in this election — racism, justice, equality, empathy and a reckoning with America’s tortured history of enslaving blacks — are universal ones. They matter in many communities across Iowa, which is 90% white and has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country for African Americans.

Dubuque is one such place.

In the late 1980s, after two cross burnings brought long-simmering racial tensions to the surface, city officials, activists and residents banded together in a campaign to make the city a more appealing place to live and work for minorities. Opponents burned more than a dozen crosses, including the ones to protest Greer’s hiring.

The rash of racist vandalism prompted some residents to put up billboards around town asking: “Why do we hate?”

Two more cross burnings in 2016 revived old fears and brought new calls for racial unity and dialogue. The culprits were never caught. Last year, racist graffiti was found at least three times at public parks.

Dubuque’s race problems appear to run deeper than the hateful actions of individuals.

The city was forced to revamp its policies in 2013 for awarding low-income housing vouchers after the federal government announced that it had violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act by “restricting the ability of African Americans to obtain vouchers and relocate to Dubuque.”

Interviews with dozens of residents, government leaders and civil rights activists suggest that after decades of soul-searching and outreach, the city’s no closer to answering the question posted on those billboards so long ago.

“It’s a sickness, and it’s a sickness that America has had since the beginning of our union,” Anthony Allen, the president of the local chapter of the NAACP, says of the way discrimination permeates life in this city — and the nation.

Allen moved here from Chicago in 1988 to attend college, and he’s watched with a mix of hope, frustration and resignation as this overwhelmingly white river city of 58,000 people has publicly wrestled with its racism.

He commends Dubuque for the way it has addressed inequities, citing the city’s decision to stop asking applicants for government jobs about their criminal backgrounds, as a way to make its hiring process fairer.

But Allen, 54, believes Dubuque has a lot of work yet to do, starting with helping whites and blacks have more constructive conversations about race.

When African Americans voice their anger and fears over the city’s racial climate, they’re often met with awkward silence or defensiveness from whites, he says.

“We’re not speaking the same language,” Allen says.

:::

In 1990, Dubuque, about three hours northeast of Des Moines, was nearly 100% white. It had fewer than 350 black residents.

The city’s plan to remake itself initially looked promising.

Local employers including John Deere, the major farm equipment manufacturer, prioritized hiring more minorities. Pastors preached against racism from the pulpit. The city’s public schools and colleges extolled multiculturalism in classrooms, and city leaders went so far as to recruit minorities to Dubuque in an effort called “constructive integration.”

Today about 3,000 African Americans live here, making up about 4% of the population, though it’s unclear how many of those arrived because of the recruitment effort.

Despite the greater number of African Americans, deep divisions are reflected in the way whites and blacks see the city’s racial issues.

Many white residents and city leaders contend that this five-time “All-America City” has been unfairly tarnished by the actions of a few bad seeds.

Many African Americans wonder how that can be true in a town that was a hotbed for the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and that was once branded “the Selma of the North” by the Des Moines Register, the state’s largest newspaper.

“How do you get past that ridiculous reputation set up by a few idiots that’s unfortunately come to represent a lot of Dubuque’s history?” asks Police Chief Mark Dalsing, a Dubuque native who is white.

‘How do you get past that ridiculous reputation set up by a few idiots that’s unfortunately come to represent a lot of Dubuque’s history?’

— Dubuque Police Chief Mark Dalsing

Dalsing says that the burned crosses and other racist acts don’t reflect his city’s values. He describes those who burn crosses as “knuckleheads.”

Lynn Sutton, who has been a member of Dubuque’s tiny African American community her entire life, looks exasperated as she walks up to a park where she says vandals have repeatedly spray-painted warnings for n— to get out.

She regards the cross burnings and graffiti as clear messages that blacks will never be welcome.

“It’s almost like we’re going backward,” says Sutton, 57, a nurse and former City Council member. “We’re not too far away from it all being turned around again.”

Still, Allen, who also chairs the city’s Human Rights Commission, says he’s encouraged that a new generation is emerging to pick up the work of the previous one.

Nancy Van Milligen, president and chief executive of the nonprofit Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque, the city’s biggest sponsor of programs aimed at improving the quality of life of minorities, says today’s leaders and residents deserve credit for quickly condemning hate crimes, and for joining forces to solve problems. She pointed to the foundation and the school district’s goal of increasing the number of black students who go to college.

But Sutton says the city should do a better job of anticipating the pain that people of color have to go through when good intentions fall short.

A two-day conference in October sponsored by the Human Rights Commission called “Race in the Heartland: The Past in the Present” came in response to a public outcry over an incident in 2018, when someone posted an anonymous letter at an apartment complex saying people of color weren’t welcome there.

The letter showed that more frank discussion was needed to figure out why Dubuque can still be a hostile place for racial minorities, says conference organizer Miquel Jackson, a 31-year-old African American who moved to Dubuque to attend college 13 years ago and who now sits on the commission.

The event ended with a public forum where several black residents aired their concerns about racism in the city — unfiltered — in front of a majority-white audience of about two dozen that listened quietly as they spoke.

Jackie Hunter is an African American from Florida who came for a job here two years ago. She told the gathering that while she recently bought a home in Dubuque, she’s thinking of leaving.

Hunter, 49, is director of the city’s Multicultural Family Center, one of the few places where young people of color feel comfortable hanging out.

Tears welled up as she talked about her 9-year-old son complaining about not fitting in and her 14-year-old daughter feeling the pressure of being the “only one” in her all-white honors classes.

“I’m still trying to find community here,” Hunter said.

:::

Dubuque may be a Northern city, but its layout is reminiscent of the strict racial divisions of Southern segregation.

Black residents largely keep to themselves in “the flats,” the low-lying, working-class neighborhood along the Mississippi River where rents are cheaper and housing is often in disrepair.

Turn-of-the-century brick and wood houses, some subdivided into apartments, line the streets, and the many old churches hark back to the city’s strong Irish and German Catholic immigrant roots.

Most whites live above the flats in more solidly middle-class neighborhoods, on a wooded bluff dotted with Victorian mansions that overlook the bridges crossing into neighboring Illinois and Wisconsin.

Dubuque’s poverty rate for black households stands at 60%, compared with about 13% for whites.

African Americans complain of unfounded stops by police.

A long-standing stereotype that blacks, especially transplants from bigger cities, are prone to commit crime is a common belief here.

White residents must acknowledge uncomfortable truths about their community and themselves if they want to build trust with African Americans who are forced to live with inequality every day, says Katrina Neely Farren-Eller, a white college professor who’s lived here for five years and has taken part in several of the city’s diversity efforts.

Among the latest efforts is Inclusive Dubuque, a coalition of business owners, educators, religious leaders and nonprofits whose aim is to make the city more welcoming and reduce racial disparities.

Farren-Eller, 52, says it’s hard to talk about her own upbringing as the daughter of avowed white supremacists, but the bottom line is this for white people such as herself: “We need to be aware of our crap.”

There are encouraging signs in Dubuque.

Recently, three dozen people from different cultures participated in “I’m a Dubuquer,” an advertising campaign featuring video testimonials and photo displays that highlight the slightly broader demographic makeup of a city long known as racist and insular.

“The idea was that nobody could look at this and not see some reflection of their identity,” said the campaign’s organizer, Sam Giere, who’s white. He went to college in Dubuque in the mid-1990s and relocated his family here in 2006.

Last fall at Soul Food Sunday, a meet-and-greet at the county fairgrounds with Southern fried chicken and African American line-dance lessons, white and black residents briefly came together in a way that earlier activists had envisioned but never quite realized.

As someone who’s experienced racism in Dubuque since birth, Sutton, the nurse, knows to be cautious about progress.

When her mother, the late civil rights leader Ruby Sutton, went into labor with her in 1962, she had to be driven to a hospital across the Mississippi River in Wisconsin. Hospitals in Dubuque refused to deliver black babies.

Now Lynn Sutton is fighting her own battles to erase inequities.

She spends much of her free time taking on landlords in the flats who’ve neglected their properties and pressuring the city to help poor minority residents get into affordable housing.

They feel trapped by their condition. The question is how do we get them out?

— Lynn Sutton, on the city’s largely low-income black population

“They feel trapped by their condition,” Sutton said of the largely low-income black population.

“The question is how do we get them out?”

Racial healing must come with economic uplift for blacks, she says: “You can’t build anything on a cracked foundation.”

::::

Jason Greer drives up to the house at the end of a cul-de-sac in the white middle-class neighborhood that his family used to live in. His father, Jerome, sits in the passenger seat. Jason is unsettled. He just feels dread.

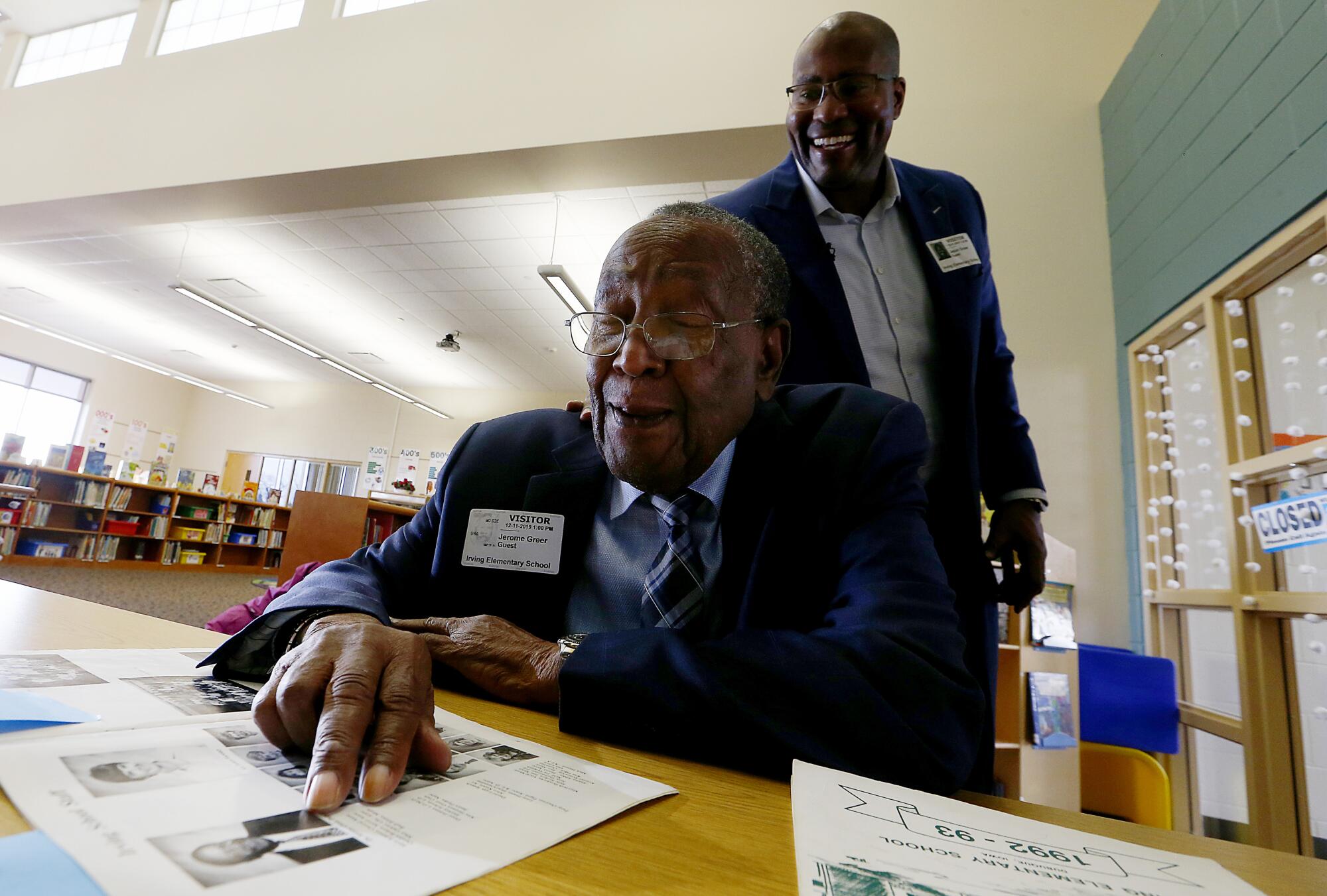

The Greers haven’t been back to this city since Jerome, now 82 and retired, moved the family two hours away to Peoria, Ill., in 1994. He says he moved for a better job.

Neither man can say why he felt compelled to come back to a city that had caused the family so much grief — and still does.

Most of the children at all-white Irving Elementary had never seen a black person up-close when Jerome Greer walked through the school’s doors in 1991.

He was not just the city’s first black principal, but also its first black school official of any kind, he says.

The children quickly warmed to him, Jerome says with a proud grin.

Jason doesn’t hold any fond memories.

It killed him to watch his father, the man he idolized, treated like an example of Dubuque’s white tolerance on one hand, and like a pariah on the other.

As father and son drive through town, Jason flashes back to the time he saw white men stretch their arms in the Hitler salute as they hurled the N-word in his direction — and to all the times white people told him to “go back where you came from.”

He mostly holed up in his basement because he feared that the verbal abuse directed at him might escalate to a physical attack.

Dressed in dark business suits and long coats to protect against the winter chill, the men stand at the site of the cross burning by the school with expressions that veer between dismay and defiance.

“My parents taught me to get an education and follow the rules and you can have whatever life has to offer,” Jason says. “Then I came to Dubuque and was treated like garbage. I left feeling like a town that I’d never heard of before took something from me — innocence.”

For his part, Jerome remembers the city’s integration plans as little more than window dressing.

He used the city’s racism as a teaching tool, taking his son around town to visit the sites of cross burnings to show him what he’d have to cope with as a black man in America.

“It really didn’t scare me,” he says of the burned crosses.

At one point, he recalls, he printed up satirical fliers intended for the town’s white supremacists that read: “If you must burn crosses, I will furnish the wood, and you furnish the kerosene and the matches. And let’s have a cross-burning party.”

Jerome regrets that his son suffered so much in Dubuque. But as someone who grew up surrounded by the brazen bigotry and violence of the Jim Crow South, he wanted Jason to see that self-pity was a waste of time.

Finally, in 2008, after his own son was subjected to taunts, Jason realized he was letting the racists win by continuing to brood over his time in Dubuque.

So he wrote two letters, one forgiving Dubuque and the other forgiving the KKK.

“I hope that one day our family can return to a racially diverse/racially accepting Dubuque,” he wrote in the letter to the city.

Jason, who lives six hours away in the St. Louis area, seems unsettled still during his daylong return. The only time his mood brightens is when he joins his father on what turns into a joyful visit to his old school.

Watching his father confidently stroll the halls of Irving Elementary like the principal he once was and poke his head into classrooms to check on the students, now a mix of races and nationalities, Jason says it’s one of the happiest moments he’s ever shared with his dad.

Although Jason can’t explain why he came back, what he does know is that he took the pain Dubuque caused him and parlayed it into a commitment to make America a more understanding and just society. He’s now a diversity consultant.

“Our country had made strides during the presidency of Barack Obama,” Jason says. “Now fast-forward. There’s a vocal minority out there that reminds me of what we experienced in Dubuque. It scares me.”

This story was reported in part with financial support from a Renewing Democracy grant awarded by the Solutions Journalism Network.

What you need to know about the Iowa caucuses, including their history, how they work and how influential they will be for Democratic voters picking their 2020 presidential nominee.

The debate over reparations for slavery is getting new attention through the 2020 presidential race. For the descendants of slaves in South Carolina, it’s personal.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.