Trump and the hurricane: How much damage did he do?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A controversy that once appeared comical — President Trump’s decision to display a crudely doctored weather map in the Oval Office — has taken on more serious overtones, with questions about how far the president will push U.S. government agencies to cover up for his errors.

Trump drew derision for refusing to acknowledge that he made a mistake when he said Alabama was threatened by Hurricane Dorian. Behind the scenes, however, administration officials were applying pressure to tamp down contradictory facts.

For the record:

8:39 a.m. Sept. 16, 2019An article about White House pressure on U.S. weather agencies after President Trump’s inaccurate statement regarding Hurricane Dorian misstated the name of an academic institution. It’s Dartmouth College, not University.

The message was relayed from acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, whose department oversees weather forecasts. Ross reportedly threatened to fire top officials at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, known as NOAA.

The goal, a senior administration official said, was “to get this behind us and fixed.”

Rather than accomplish that goal, the administration’s moves have only inflamed the situation.

Although a spokesperson for the Department of Commerce has denied that Ross threatened to fire anybody, the inspector general has begun a review of whether rules intended to safeguard scientific integrity were broken. Congressional Democrats, who have already lined up enough investigations to last several presidencies, have vowed to launch another inquiry.

The rules on scientific integrity were intended to safeguard research on controversial topics like climate change. Monica Medina, a former administrator at NOAA during the Obama administration and an environmental advocate, said she “never thought that they would have to be using it for a weather forecast.”

“This is just beyond anything we could have imagined,” she said.

The episode is an example of how Trump can transform a fleeting mistake into a potentially more damaging scandal in an attempt to shield himself from even minor embarrassment.

It’s also a reminder of how he’s politicized normally nonpartisan government functions — such as projecting the path of a deadly natural disaster — and turned them into loyalty tests in which his version of reality is the only acceptable one.

“We’re seeing this administration grinding down the resistance to political influence,” said Brendan Nyhan, a professor of government at Dartmouth University. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable to fear that people might put less trust in the government going forward.”

The controversy began Sept. 1, when Trump falsely claimed that Alabama was among several states that would be “hit (much) harder than anticipated” by the storm. The president’s tweet appears to have been based on outdated information; Alabama was no longer in the storm’s path by the time he wrote it.

In order to stem any panic, the National Weather Service’s office in Birmingham, Ala., quickly clarified that the state would not be affected. But Trump was unable to abide the contradiction or the subsequent media attention.

In the Oval Office on Sept. 4, he held a poster-sized weather map showing Dorian’s initial trajectory. A black line, hand-drawn with a Sharpie marker, showed the storm’s path extending to Alabama.

The next day, the White House issued a statement from a rear admiral who serves as Trump’s Homeland Security advisor, saying that Trump had been briefed on the possibility that Alabama was under threat.

The day after that, NOAA issued an unsigned statement that undermined the Alabama office’s decision to correct the president.

“The Birmingham National Weather Service’s Sunday morning tweet spoke in absolute terms that were inconsistent with probabilities from the best forecast products available at the time,” the statement said.

Craig McLean, the acting chief scientist at NOAA, issued a rebuttal in a message to the agency’s staff.

“My understanding is that this intervention to contradict the forecaster was not based on science but on external factors including reputation and appearance, or simply put, political,” he wrote.

For people who study public administration and democratic governance, the fallout over the weather forecast rang alarm bells.

“This is just part of a pattern,” said Brian Klaas, a political scientist at University College London. “It is extremely unusual in democratic countries, and extremely common in authoritarian states.”

When working in these kinds of administrations, Klaas said, “the job becomes more about supporting the regime and supporting the leader, and less about giving nonpartisan information or the truth.”

“You hate to make banana republic comparisons, but when you see the expertise of the career service undermined, those comparisons become inevitable,” said Donald Moynihan, a Georgetown University public policy professor who specializes in government administration.

The cost could be long-term degrading of the federal workforce, he said. “If you care about science and evidence and facts, and invested a lot in your education, why would you work at a workplace where you know those values are going to be undermined?”

The stress is already showing at NOAA.

Neil Jacobs, the organization’s acting director, choked up while speaking at the National Weather Assn.’s annual conference in Alabama this week.

“This is hard for me,” he said.

Jacobs defended his agency’s unsigned statement and denied that anyone’s job was under threat. But he also voiced his support for government forecasters.

“Weather should not be a partisan issue,” he said.

But Trump has shown a knack for turning even the most benign topics into political wedges. His campaign started selling “Official Donald J. Trump Fine Point Markers” that supporters can use to “set the record straight!” A pack of five costs $15.

It’s consistent with how Trump has handled other information since taking office.

“He acts and speaks as if he doesn’t believe in the existence of nonpartisan information,” said Timothy Naftali, a professor of public service at New York University.

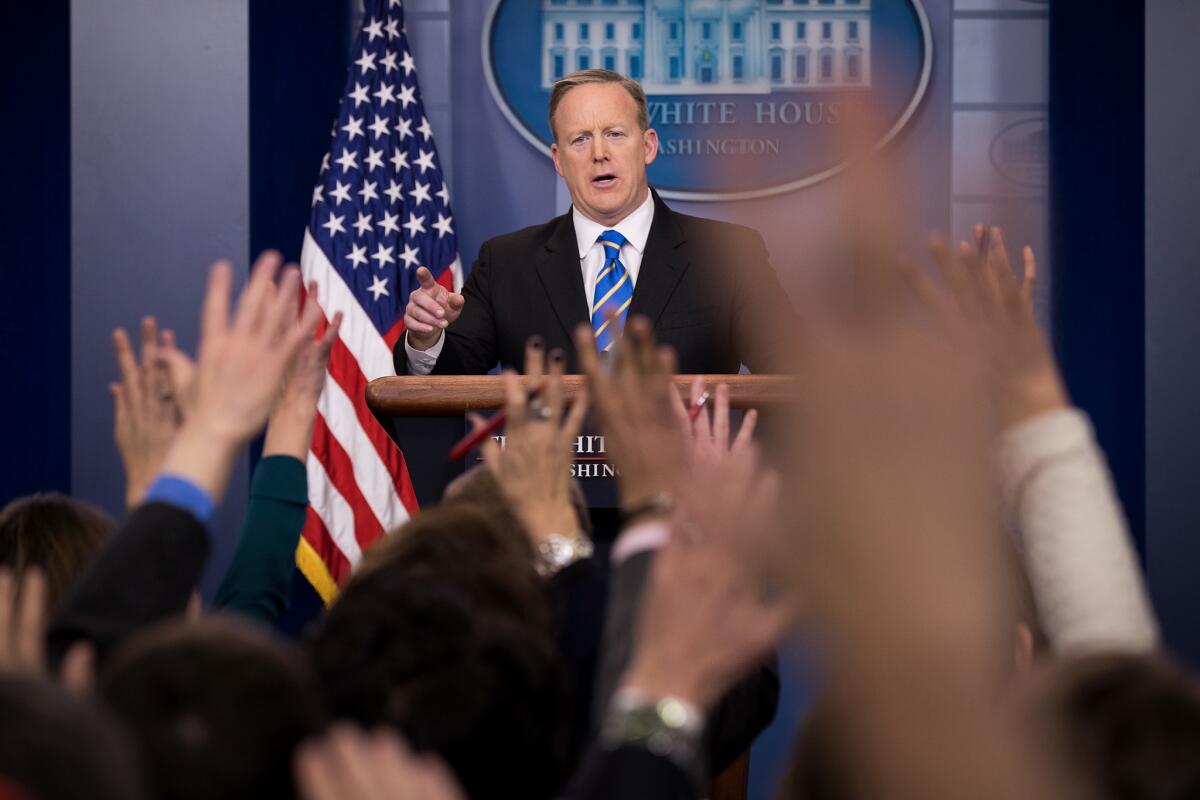

One of the most brazen examples came early in his term, when Sean Spicer, then the White House press secretary, was touting government statistics showing job growth.

Trump had previously claimed without evidence that under President Obama, the numbers were doctored. But now that the figures benefited him, he was willing to accept them.

“I talked to the president prior to this, and he said to quote him very clearly,” Spicer said. “‘They may have been phony in the past, but it’s very real now.’”

Many of Trump’s attempts to justify falsehoods involve situations in which his ego is threatened. For example, he’s always seethed over losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton in 2016, which he justified by claiming that “millions” of people voted illegally.

He created a commission ostensibly to investigate the matter; although no evidence was ultimately found, Trump claimed that the panel uncovered “substantial evidence” of fraud.

The president’s refusal to admit facts about his trademark campaign pledge to “build the wall” has forced his top officials into rhetorical contortions.

Mark Morgan, the acting commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, confirmed in a recent media briefing that not a single new linear mile of border wall had yet been completed under Trump. The roughly 700 miles of fencing along the nearly 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border were all constructed under Trump’s predecessors.

But at the White House on Monday, Morgan called that fact a “false narrative” and disputed the definitions of “new wall.”

There are now “more than 65 miles of new border wall,” Morgan said, but he did not mention that those are replacements for barriers already in place, rather than new miles of barriers.

Times staff writers Noah Bierman, Eli Stokols and Molly O’Toole contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.