State Senate bills aim to make homes more affordable, but they won’t spur nearly enough construction

A trio of bills aim to alleviate California’s housing affordability crisis. (Aug. 11, 2017)

Last month, Gov.

But the measures now contemplated to alleviate the state’s affordability crisis will not make much of a dent in California’s housing needs, according to analyses from state officials and housing groups. Even if high-profile housing bills pass, the state would need to find at least an additional $10 billion every year for new construction just to help Californians most burdened by high rents.

The three marquee measures under consideration — Senate Bills 2, 3 and 35 — aim to increase funding for low-income housing projects and ease development regulations. The measures are unlikely to help spur enough home building in general. Development would still fall short by tens of thousands of new homes needed annually just to keep pace with projected population growth.

“If [lawmakers] get a package that includes SB 2, SB 3 and some version of SB 35, it is reason to celebrate,” said Jim Mayer, the president and CEO of California Forward, a nonprofit that has urged the state to act more aggressively on housing. “But it won’t have solved the problem, and nobody in their communities is going to think it’s solved the problem.”

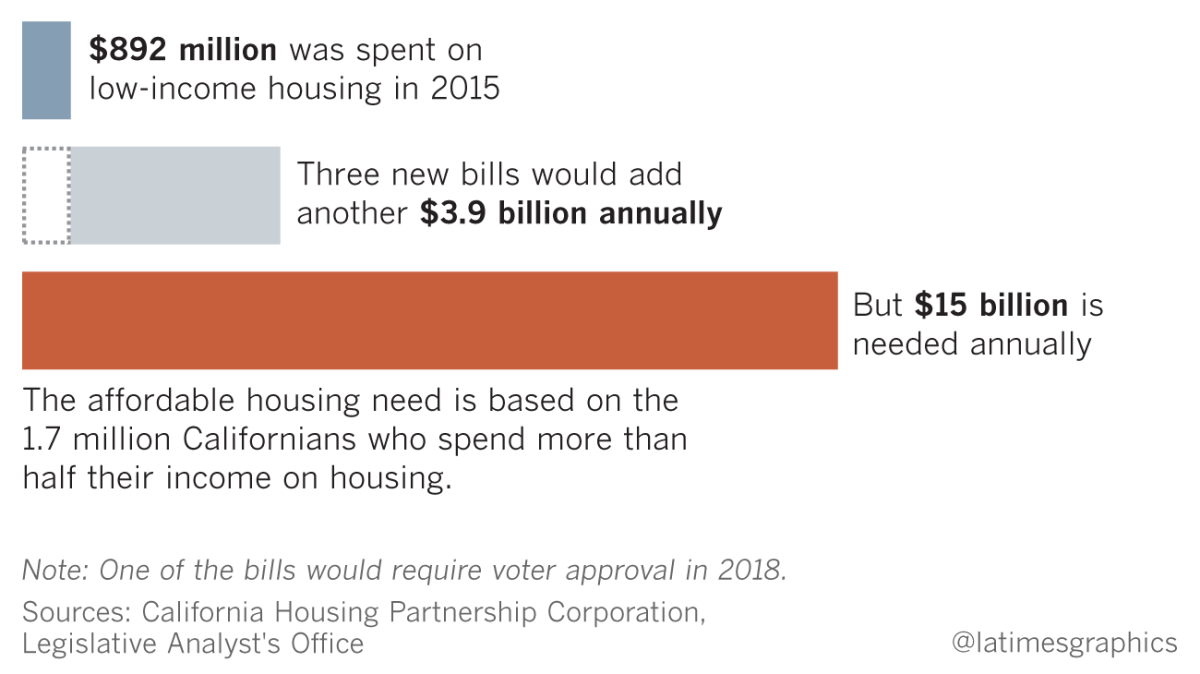

About 1.7 million low-income California renters spend more than half their income on housing. Helping to finance new homes for those residents alone would cost the state at least $15 billion a year, according to an estimate from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, an amount roughly equivalent to state spending on Medi-Cal.

Senate Bill 2 would add a $75 fee on mortgage refinancings and most other real estate transactions except for home and commercial property sales and funnel the money toward low-income housing financing. Senate Bill 3 would place a $3 billion bond on the 2018 statewide ballot also to help build low-income projects.

Neither bill is a sure thing — they require two-thirds votes in both houses of the Legislature. Some influential Democrats likely needed to vote in favor of SB 2 are already balking at raising fees. And voters will ultimately decide the bond’s fate.

If both measures pass and their funding is combined with private investment and federal and local dollars, they could raise about $3.9 billion a year, according to an analysis by the California Housing Partnership Corp., a nonprofit low-income housing advocate. But current federal and state funding for low-income development remains low, leaving the overall $10-billion gap in spending needs.

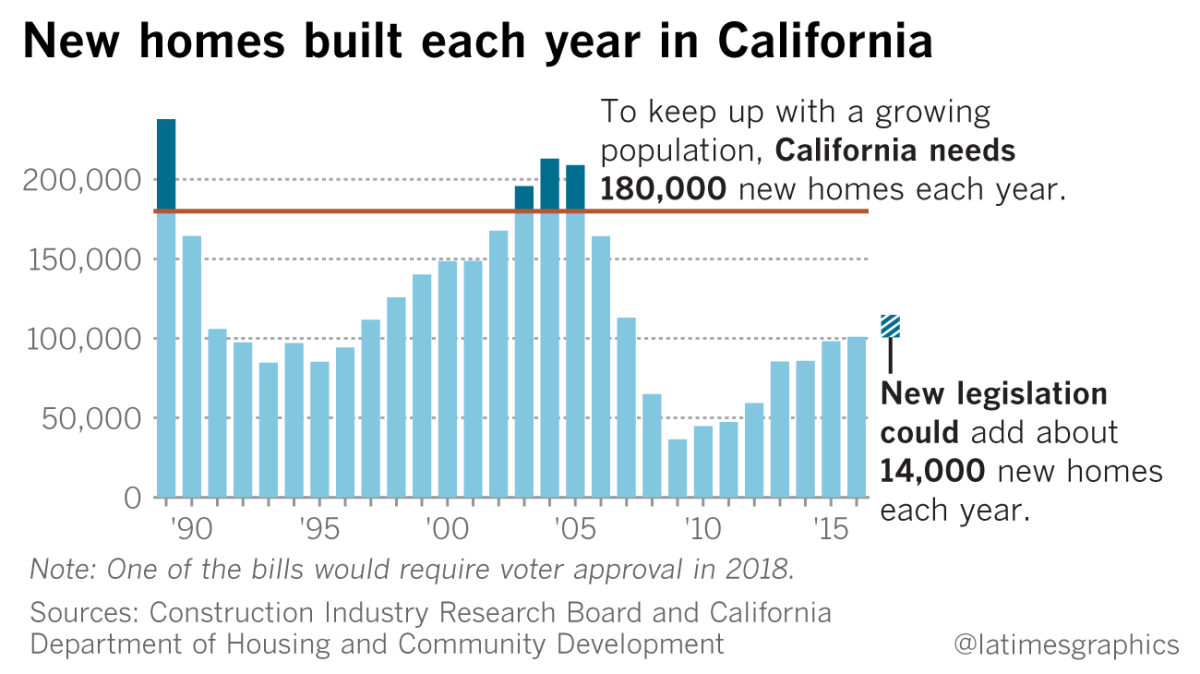

A similar shortfall exists in home building. Developers need to construct 180,000 new homes annually just to accommodate California’s projected population growth, according to the state Department of Housing and Community Development.

Developers in the state have built more than 180,000 homes a year in just three years since 1989, according to permit data from the construction industry. The low amount of building has contributed to a longstanding housing shortage that’s led to sky-high prices. Roughly 101,000 new homes were built last year.

The revenue generated from Senate Bill 2’s real estate fee and Senate Bill 3’s bond funding could help finance the development of about 14,000 homes a year, according to the California Housing Partnership Corp. estimate, leaving a gap of 65,000 houses. Even more home building would be needed to account for prior shortfalls, which would help reduce housing costs.

Moreover, the bond money authorized by Senate Bill 3 could be spent in as little as five years, and the funding and home building gaps would get larger after that.

The goal of Senate Bill 35 is to make it easier to build homes. It would require cities and counties to limit environmental, planning and other reviews on land already zoned for a developer’s proposed amount of housing. The effort aims to give developers more certainty that their projects will get built, saving them time, money — and increasing the housing stock. A 2014 state study of low-income housing development found projects that needed approval at multiple local boards cost at least 5% more to build.

But the bill’s author, Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco), said he’s not sure how many new homes the measure would help produce.

“The state is too big and diverse to accurately predict a number,” Wiener said.

Last year, Brown proposed a similar measure and a UC Berkeley estimate found it could have created up to 2,350 homes total in San Francisco, for instance.

Brown’s effort failed, and Wiener’s approach is more narrow. Brown’s plan would have affected every city and county in the state, but Wiener’s only applies to local governments that have fallen behind on state goals for home building in their communities. Wiener also would require developers who want speedier local reviews for their projects to pay construction workers higher wages and accept union-level hiring standards, which some business interests have criticized as being too costly.

Wiener said that reducing local government regulations and adding new funding for low-income developments are significant in addressing the state’s housing problems.

But the state, he said, ultimately will have to look at bigger-ticket items, such as making it more financially beneficial for cities to approve housing developments and giving state and regional governments a larger role in approving large, transit-friendly projects if local governments are opposed to them.

“We need to be very clear that passing this package doesn’t mean that the Legislature is done with housing,” Wiener said. “We can’t check that box. It’s going to take years.”

Lawmakers are expected to vote on the housing bills when they return from their summer recess later this month. The deadline for passage is Sept. 15 when the legislative year ends.

ALSO

A Bay Area developer wants to build 4,400 sorely needed homes. Here's why it won't happen

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.