Column: Political Road Map: A sloppy signature might keep your 2018 ballot from being counted

- Share via

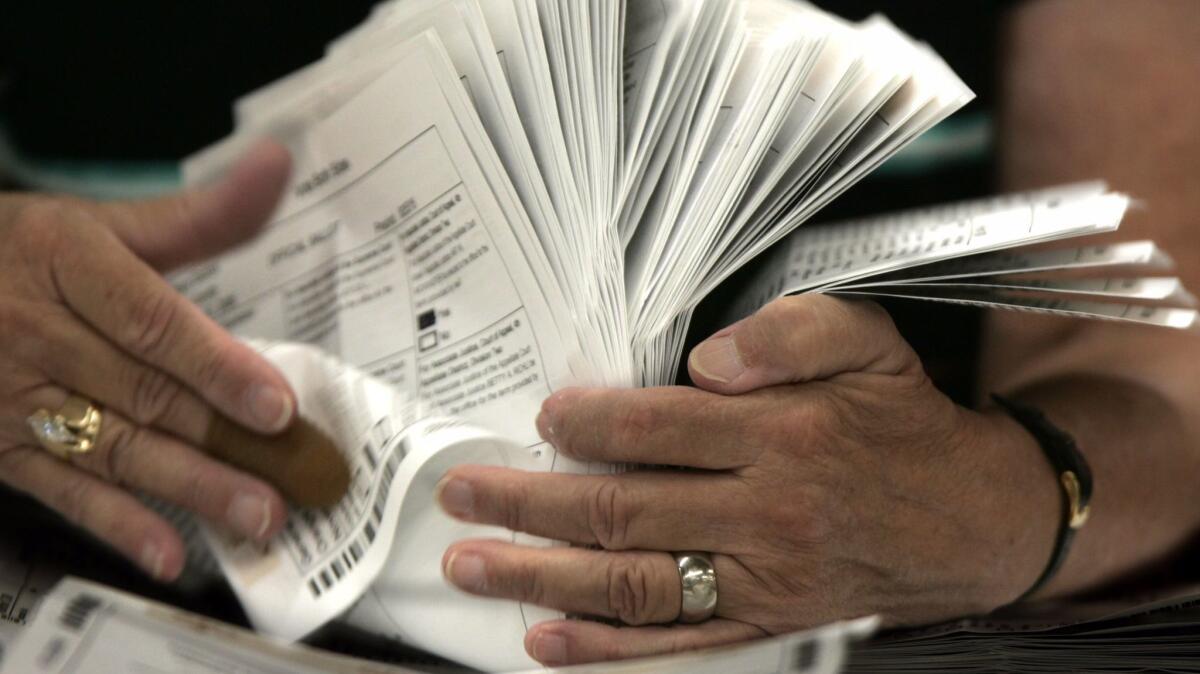

Reporting from Sacramento — Few Californians are likely to spend any time thinking about how carefully they signed their voter registration card years ago. Nor is there much reason to assume that those who vote by mail think much about the neatness of their signature on the envelope containing that absentee ballot.

But those two signatures — and whether they’re deemed to match — actually are key to whether the ballot counts. And while voting absentee was once uncommon, it’s now used by millions of Californians, some who will be newly pushed into doing it come 2018.

The reality is that current California law is so flexible as to be vague when it comes to what an elections official should do when faced with an absentee voter’s sloppy signature. It simply states that the ballot counts if the official “determines that the signatures compare.”

State law, argues a lawsuit filed in August by the ACLU of Northern California, doesn’t say “how elections officials should make this determination” or require “training in handwriting identification or comparison.” The case is centered on a Sonoma County voter whose ballot was rejected because of his signature. It argues his constitutional right to equal protection was violated because no one allowed him to fix the signature problem.

California isn’t the only place where this is happening. It’s the same problem pointed out in 2016 by a Florida judge, who ruled it was illegal to not count a voter’s absentee ballot “for no reason other than they have poor handwriting or their handwriting has changed over time.”

In California, the ACLU lawsuit argues that some 45,000 ballots were discarded last November with mismatched signatures cited as the reason. Elections officials concede that there’s no guide for what to do when a 50-year-old woman, who last signed her voter registration form when she was 18, now has a different signature.

“I think we need to have more clarity, and more direction in how we can assist voters,” said Gail Pellerin, the registrar of voters in Santa Cruz County.

Pellerin and her staff spend a lot of time tracking down voters whose signatures don’t match when the ballot arrives in the mail. (And she has a tip for people who have registered online since 2012: Pull out your driver’s license as a guide before signing the ballot envelope, because that’s the signature on file for those voters.)

California’s signature-matching system was fine prior to 1978, when absentee voting was limited to a medical excuse or being out of town on election day. Now, with permanent absentee voting allowed, it’s hugely popular. Last November, 61% of all registered voters received a ballot in the mail.

And that’s expected to grow substantially. In 2018, as many as 14 counties will be allowed to move toward almost all-mailed ballots under a new law swapping neighborhood polling places for a limited number of community “vote centers.” By 2020, all counties will be allowed to make the shift. That could greatly increase the pressure on an outdated signature verification process.

It’s true that state law says decisions governing absentee ballots should “be liberally construed in favor of the vote by mail voter.” But that’s the extent of the guidance. In short, elections officials in each California county — unless lawmakers in Sacramento take action — can use whatever standard they want when deciding what’s in a name.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO:

Political Road Map: Don’t miss the fine print in this big California campaign disclosure bill

Political Road Map: California’s gas tax increase could give Republicans an electoral lifeline

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.