Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom to place California wineries, hotels in blind trust

Reporting from Sacramento — Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom on Thursday announced he will place his ownership interest in the collection of wineries, hotels, restaurants and other investments that made him a millionaire into a blind trust, a step he said “goes beyond anything required by law.”

Since his election in November, Newsom has been weighing how to handle his array of assets in the hospitality business, collectively known as the PlumpJack Group, a multimillion-dollar business enterprise that grew from a wine shop he opened in San Francisco in 1992. Those holdings have the potential to create ethical conflicts between Newsom’s job as California’s chief executive and his business interests.

“Governor-elect Gavin Newsom is announcing today that he will be the first governor in the history of California to release his tax returns every year, just as he has done as a candidate,” Newsom’s spokesman Nathan Click said in a statement. “Newsom will also disclose his personal and business holdings each year on his statement of economic interest and separate himself from the PlumpJack Group wine and hospitality businesses that he has built.’’

Bob Stern, coauthor of California’s 1974 Political Reform Act that dictates the state’s conflict-of-interest laws, praised Newsom’s decision.

“That’s as much as anybody could ask him to do, except for selling all the properties, which I wouldn’t recommend him doing,” Stern said Thursday.

Stern added, however, that placing those assets in a blind trust does not remove the potential that Newsom could face a possible conflict of interest as governor. Under the law, Newsom is required to disclose all assets in the blind trust until those assets are sold, Stern said.

Newsom is in the process of transferring title to and control of the businesses into the blind trust, Click said. Newsom selected family friend Shyla Hendrickson, an attorney and certified public accountant with more than two decades of experience in the investment management business, as trustee, he said.

Under the terms of the blind trust, Hendrickson will have total authority over the assets, Click said, including the power to sell off Newsom’s business ownership without consulting him. She also is barred from discussing those decisions with Newsom.

Picking a family friend to serve as trustee is allowable under state law, Stern said, adding that the fact that Newsom’s sister, Hilary Newsom Callan, serves as president of the PlumpJack Group is “not a problem” under the law.

State law does not require Newsom to divest from PlumpJack Group or release the names of his business associates. And Newsom can legally sign bills or take executive action beneficial to his companies if those decisions affect all Californians or a significant segment of the population in the same way they affect him.

Newsom has yet to announce any details about the financial interests of his wife, documentary filmmaker Jennifer Siebel Newsom, whose foundation could also raise questions for the incoming governor.

Siebel Newsom’s foundation, the Representation Project, which helps fund her documentaries along with education programs and community outreach “to challenge limiting gender stereotypes and shift norms,” has in the past received financial support from Pacific Gas & Electric Co. and AT&T. PG&E and its foundation reported donating $100,000 to the Representation Project in 2017, $85,000 in 2016 and $10,000 in 2015, according to federal tax records and a list of PG&E’s charitable donations on the utility’s website.

As president of the foundation, Siebel Newsom received a salary of $150,000 in 2016, according to the most recent publicly available disclosures filed with the Internal Revenue Service. The foundation also reported paying Girls Club Entertainment, Siebel Newsom’s production company, $150,000 that same year. Newsom’s spokesman said the board of directors of the Representation Project is in the process of determining her future role with the foundation.

In 2018, PG&E also donated $58,400 to Gavin Newsom’s gubernatorial campaign and $150,000 to Citizens Supporting Gavin Newsom for Governor 2018, an independent expenditure committee that backed his candidacy.

Next year, the California Legislature is likely to consider a bill to provide financial relief for any utility whose equipment was involved in a wildfire in 2018. PG&E could face billions in potential liability costs for the deadly Camp fire near Chico, which killed at least 86 people and destroyed thousands of homes.

If approved by lawmakers, the bill would land on Newsom’s desk.

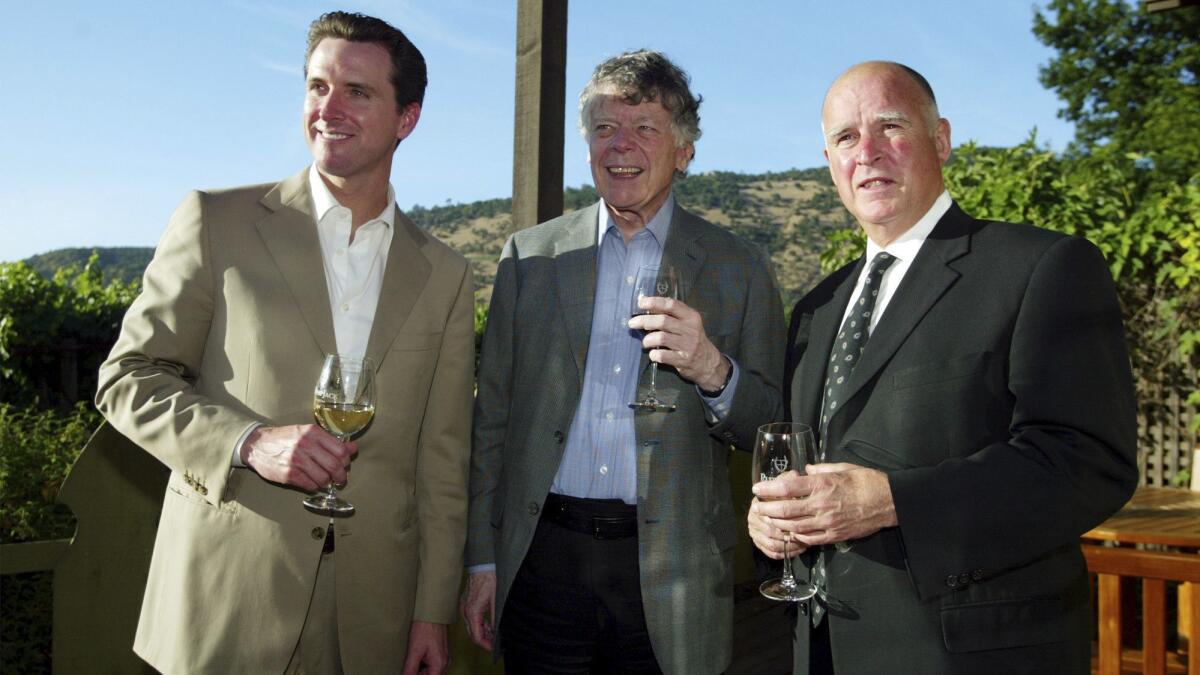

This isn’t the first time Newsom has had to address the intersection of his political and business lives. After he was elected mayor of San Francisco in 2003, Newsom sold his interests in the PlumpJack Group businesses in San Francisco to his longtime friend and business partner, oil heir Gordon Getty, for $1.7 million, according to a financial disclosure filed with the city. But Newsom held on to his investments outside the city limits, including in Napa Valley wineries and a hotel and gift shop at the Squaw Valley ski resort near Lake Tahoe.

“The mayor chose to take this unprecedented action because he feels it is in the best interest of San Francisco for its chief executive not to own businesses that operate in the city,” Newsom’s then-press secretary, Peter Ragone, told the San Francisco Chronicle in April 2004.

As governor, Newsom could face an array of potential ethical dilemmas as long as his assets in the PlumpJack Group remain in the trust.

For example, a corporation could conceivably try to curry favor with the new governor by renting out a bank of rooms at the PlumpJack Squaw Valley Inn or by throwing lavish parties at the Forgery bar in San Francisco, both among Newsom’s holdings. In those scenarios, the spending would likely not have to be disclosed.

Newsom has held campaign events at his restaurants and other businesses for years. His gubernatorial campaign spent more than $83,000 at his businesses from 2015 through election day, campaign finance records show.

In 2014, the California Democratic Party held a fundraiser at Newsom’s CADE Estate Winery in Napa Valley, paying the business $4,229. Just after Newsom was elected mayor of San Francisco in 2003, two Bay Area labor groups spent more than $1,000 at PlumpJack Wines, Newsom’s wine store.

Newsom has vowed to issue an executive order prohibiting state executive branch agencies from doing business with PlumpJack entities. He will also divest from all common stock that he owns in publicly traded companies. According to his latest financial disclosure, Newsom held stock in Intel Corp. and Merck & Co. worth $4,000 to $20,000 in total.

Napa Valley wineries have brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars in income for Newsom annually, according to financial disclosure records and business filings with the secretary of state’s office. Three wineries in the PlumpJack Group founded by Newsom and Getty generated nearly $800,000 in just one year for Newsom, according to his 2015 federal tax returns. Newsom and Getty — who are connected through Getty’s friendship with Newsom’s late father, who once managed Getty’s family trust — share multiple business interests.

Under state law, Newsom will not have to declare a conflict of interest when making a decision — whether to sign legislation or approve an administrative action — unless it “explicitly” affects one of his companies or investments, according to state Fair Political Practices Commission regulations.

For example, Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) is sponsoring a bill that would allow bars in San Francisco, Los Angeles and seven other cities to serve alcohol until 4 a.m. The legislation passed this year but was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown. If the bill passes again in the new legislative session, Newsom’s restaurants and bars would benefit financially if he signs it. But he still would be able to so without declaring a conflict of interest because the rules would apply to all restaurants and bars in those cities, not just his.

“He’s certainly allowed to sign bills dealing with wineries or dealing with restaurants,” Stern said.

Although Newsom might be one of the wealthiest governors ever to serve in California, the issues posed by his assets aren’t new to the office, Stern said.

Former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger sold off stock and many other investments, placing the proceeds in a blind trust, although he had also disclosed investments outside the trust, including his Hollywood entertainment firm, Oak Productions.

While in office, Schwarzenegger was criticized for accepting a consulting job for a publisher of health and bodybuilding magazines — Muscle & Fitness and Flex — because a significant portion of the publications’ revenue came from advertising by makers of nutritional supplements. Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill that would have created a list of banned substances for interscholastic sports and barred supplement manufacturers from sponsoring school events.

Rob Stutzman, a GOP strategist and former communications director for Schwarzenegger, said it was difficult to wall off some of Schwarzenegger’s business interests because they were tied to the “personal brand” of the Hollywood action star and former champion bodybuilder.

The best option in those cases is asking full disclosure from public officials, he said.

“I don’t think [Schwarzenegger’s situation] is unique. I think it’s just a matter of scrutiny and watching it,” Stutzman said.

“In Newsom’s case, if he can’t sell PlumpJack or other things he owns, he’s not going to be blind,” said retired attorney Colleen McAndrews, a former member of the state Fair Political Practices Commission who advised Schwarzenegger on setting up a blind trust when be became governor.

Coverage of California politics »

Local government politicians are most affected by the state’s conflict-of-interest law because cities and counties approve regulations, permits, land use restrictions and other items that could affect a single business or part of town. It would be rare to see a conflict arise under state law for the governor, however, because most of the action taken by the state’s chief executive affects all Californians equally, McAndrews said.

“You don’t have to recuse if a decision affects the public the same way it affects you,” she said.

Rick Scott, the wealthiest governor in Florida history who in November was elected to the U.S. Senate, came under intense scrutiny after he placed his assets in a blind trust. Multiple Florida news outlets reported that Scott’s blind trust made identical investments in a separate, private account for his wife, raising questions about just how “blind” the governor was to the trust.

GateHouse newspapers reported this year that the couple’s financial holdings in the pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, which makes drugs to combat hepatitis C, had grown substantially. Florida’s Medicaid program has spent millions on those drugs, the report found.

Jamie Court, president of the nonprofit Consumer Watchdog, said that regardless of what the incoming governor decides to do regarding his assets, Newsom should provide full disclosure of all his financial interests.

“I think the governor has to be very open about his business relations, even beyond what the law calls for,” Court said. “If he hides anything, believe me, we will find out later and it won’t be good.”

Times staff writer Maloy Moore contributed to this report.

Twitter: @philwillon

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.