California lawmakers have a $190.3-billion state budget plan to consider. Here’s some of what it would pay for

Insisting that California lawmakers continue to restrain government spending growth in preparation for a recession he believes is just around the corner, Gov. Jerry Brown on Wednesday unveiled a state budget for 2018 that proposes banking most of a $6.1-billion tax revenue windfall expected to show up in the fiscal year beginning July 1.

Most of the money would be placed into the state’s primary reserve fund, a savings account that would grow to $13.5 billion — the largest such crisis contingency fund in California history.

Here are some of the key parts of the budget the Legislature will now consider. A final agreement is due on Brown’s desk by June 15.

Where would the $6.1 billion in unexpected tax revenue go?

- $3.5 billion would go to an extra payment into the state’s Budget Stabilization Account, often called the “rainy-day” fund. By law, this account can grow to 10% of general fund revenue, and Brown’s budget would get it to that maximum limit by early summer of 2019.

- $2.3 billion would be used for costs that arise during the fiscal year, what the budget calls “economic uncertainties.” This could include things like responding to natural disasters. Unlike the rainy-day fund, lawmakers have a significant amount of discretion over this money.

- $134 million would be used to help pay for outdated voting and election equipment in California’s 58 counties, though this is only half of the needed funds and the rest would have to be provided by local governments.

- $100 million would be used to boost funding to help those who have been found incompetent to stand trial. State officials say that court referrals of these defendants are now almost one-third higher than five years ago and that 840 people were on the wait list for inpatient mental health treatment as of December.

- $30 million would be used to create the California Institute to Advance Precision Health and Medicine, with a mission of improving health and healthcare through advanced computing and technology.

- $16 million would go toward California’s earthquake warning system.

As always, schools get most of the state’s cash. But is it enough?

In 1988, voters approved an amendment to the California Constitution that sets aside the single largest portion of tax revenue for K-12 schools and community colleges. That accounts for about 42 cents of every dollar in the state’s general fund.

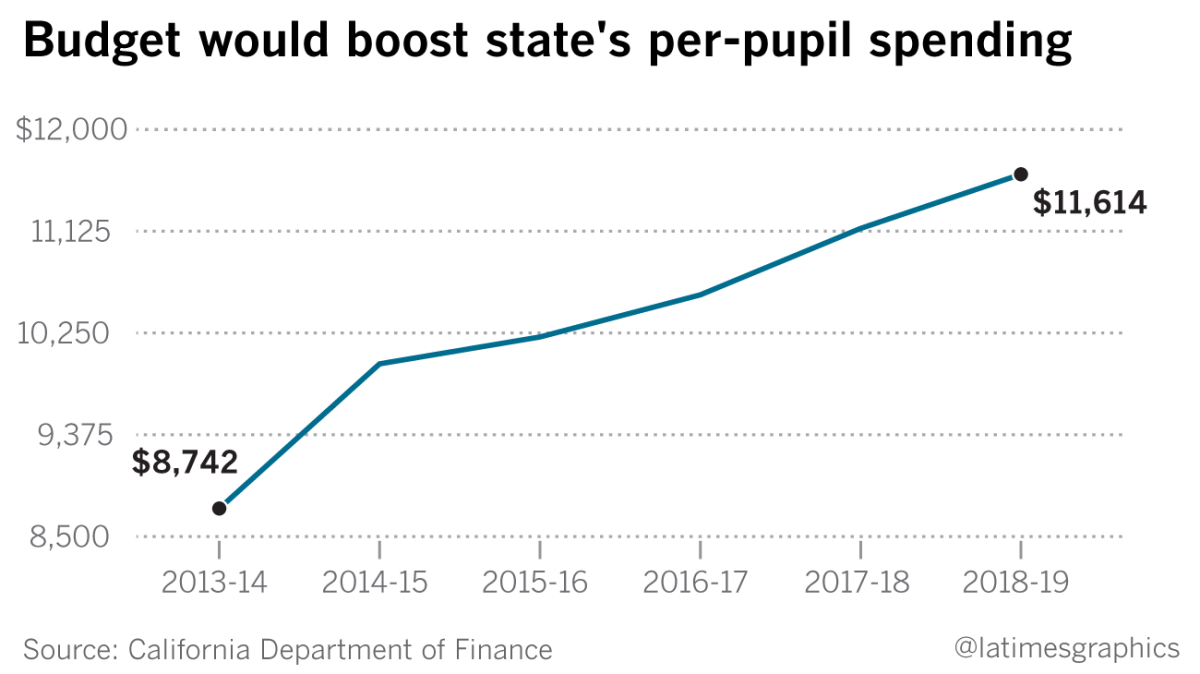

Overall, Brown’s budget estimates that the voter-approved mandate translates into $78.3 billion for schools next year, a combination of local property taxes and state income taxes. That’s about $11,614 per student — and even more if repayment of debts owed to schools is included. The state Department of Finance estimates a $465 per-pupil boost from the current year. Even so, California will remain near the bottom of all states in per-pupil funding.

The governor’s budget plan also directs more money to his 2013 effort that prioritized funding for disadvantaged students and additional local discretion on how to spend money.

In California government, nothing is more costly than health and human services

Though it’s true schools get most of the state’s dollars, a broader view that comprises both state and federal dollars reveals education is not California’s top expense.

That distinction goes to health and human services, of which the new budget proposal pegs the total cost at $155.7 billion, with 60% coming from the federal government. That’s more money than every other state spent from all sources on all programs in 2016, according to data from the National Assn. of State Budget Officers.

Medi-Cal, the program providing healthcare services for low-income Californians, accounts for almost two-thirds of the spending. Almost 13.5 million people are enrolled in Medi-Cal, with a sizable number joining the program through money provided by the Affordable Care Act. The law requires the state’s share of the costs to steadily rise through 2020. But given the uncertainty over Obamacare’s future, no part of California’s government services may be more vulnerable. Brown’s budget says repealing the law would cost the state “tens of billions of dollars annually.”

The In-Home Supportive Services program, which provides care to an average of 545,000 aged and disabled people per month, is the second-largest spending item in this category. Costs are now $11.2 billion a year — more than double what they were eight years ago, while caseload has risen by only 26%.

Welfare assistance, programs for the developmentally disabled and public health are among the other, smaller programs. Democrats in the Legislature will probably ask Brown again to boost some of these services — especially those that haven’t received inflation-adjusted increases in recent years.

Fighting California wildfires is now a budget expense worth watching

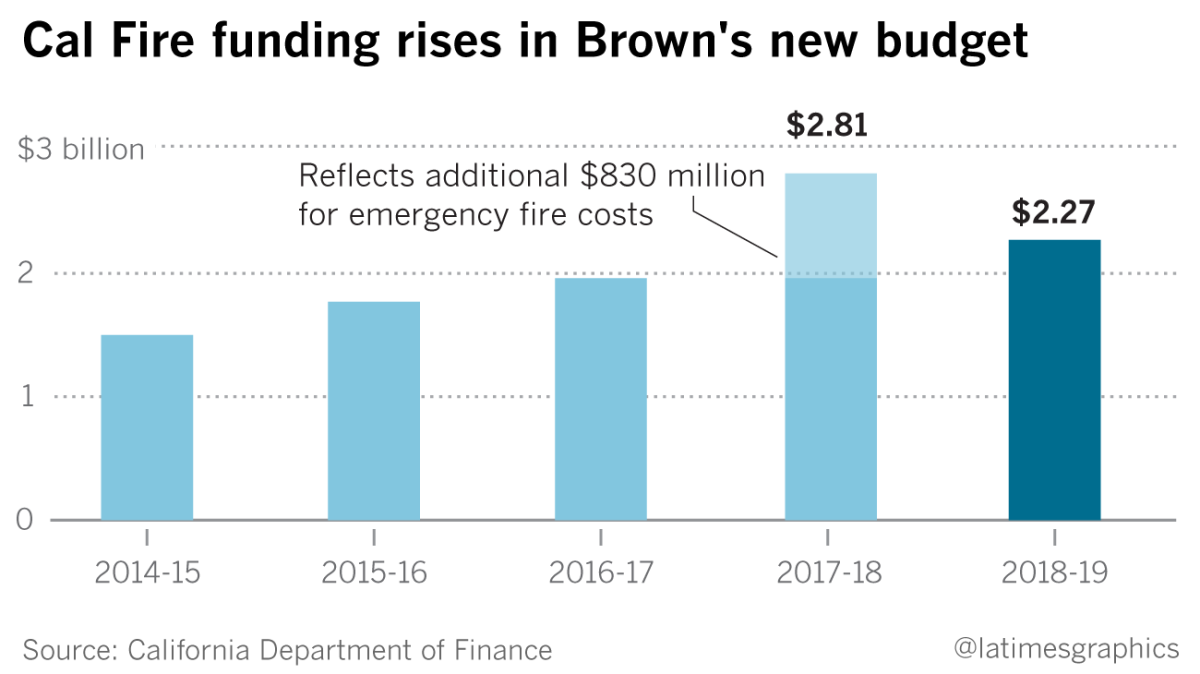

After one of the most devastating wildfire seasons in state history, California’s state government has spent much more than expected on battling the blazes. Costs are now $830 million higher than expected for the budget year that ends June 30.

In the coming fiscal year, Brown is proposing a higher base level of spending for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection — $1.3 billion higher than just four years ago. Lawmakers may want to take a close look at the long-term climate trends in the Golden State and ask themselves: How much needs to be set aside to better handle the fires of the future?

The governor’s budget includes scores of smaller items, from pensions to pot

- The cost to taxpayers of public employee pensions continues to be a source of political debate. Brown’s plan assumes a $6.2-billion payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS — a $389-million increase from 2017-18. The budget projects a payment of almost $3.1 billion to the teachers’ pension fund, CalSTRS.

- Tucked inside of the budget for corrections is $3.8 million for a pilot program aimed at helping juvenile offenders. The plan would divert a limited number of inmates between the ages of 18 and 21 to two juvenile facilities for “specialized rehabilitative” help to reduce their chances of committing crimes in the future. A similar pilot program has been used in five Northern California counties.

- The governor’s budget plan includes more than $80 million to replace roofs and remove mold at several state prisons.

- When voters approved the legalization of recreational marijuana in 2016, the ballot measure promised pot taxes would pay back state costs for regulations and enforcement. Brown expects $135 million in lent cash to be paid back to the state’s general fund by next summer.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.