After decades of suburban sprawl, San Diego eyes big shift to dense development

Reporting from San Diego — San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer thinks his city has said “no” to housing for too long.

Where it once grew by sprawling — with political leaders in the middle of the last century annexing hundreds of square miles from the San Pasqual Valley near Cleveland National Forest to the border with Mexico — today San Diego is planning for an urban development boom so people don’t have to drive to work.

For the record:

2:15 p.m. Feb. 25, 2019An earlier version of this article said residents living near San Diego’s Balboa Park protested a proposed 20-story condominium complex by wearing all black and holding up black umbrellas. The residents were protesting a 20-story apartment complex.

But that growth hasn’t happened yet, and the city’s housing costs are escalating.

So in his State of the City address in January, Faulconer proposed some of the most aggressive strategies of any California city to promote apartment and condominium construction. For San Diego residents to live affordably, the mayor said, the city must stop obliging long-held community demands to keep buildings short and stop requiring new parking spots so people have more places to live.

“We must change from a city that shouts ‘Not in My Backyard’ to one that proclaims ‘Yes in My Backyard!’ ” Faulconer said in the speech.

The mayor’s plans are part of a broader shift taking place in larger cities across California to promote growth, especially near transit stops. They also align with a push by Gov. Gavin Newsom and some state lawmakers to crack down on local development restrictions, which they believe are a major driver of California’s rising housing costs amid continued calls by neighborhood groups to shrink or deny building projects.

“There’s no question that larger cities in California are taking aggressive steps,” said Bill Fulton, publisher of the California Planning and Development Report. “That’s really accelerated in recent years as housing has become more of an issue.”

After Huntington Beach lawsuit, Newsom warns cities he’ll continue housing law crackdown »

In December, San Francisco got rid of requirements for developers to install parking spots alongside new homes across the city. In the same month, Sacramento passed a plan to phase out car-centered developments, such as fast food drive-through restaurants, in the city’s downtown and other areas near transit — part of a bid to make it easier to build apartments and condominiums. And nearly three years ago, Los Angeles voters passed a plan that allows developers to build taller and more densely and receive permits more quickly for projects near Metro stations that set aside some units for low-income residents.

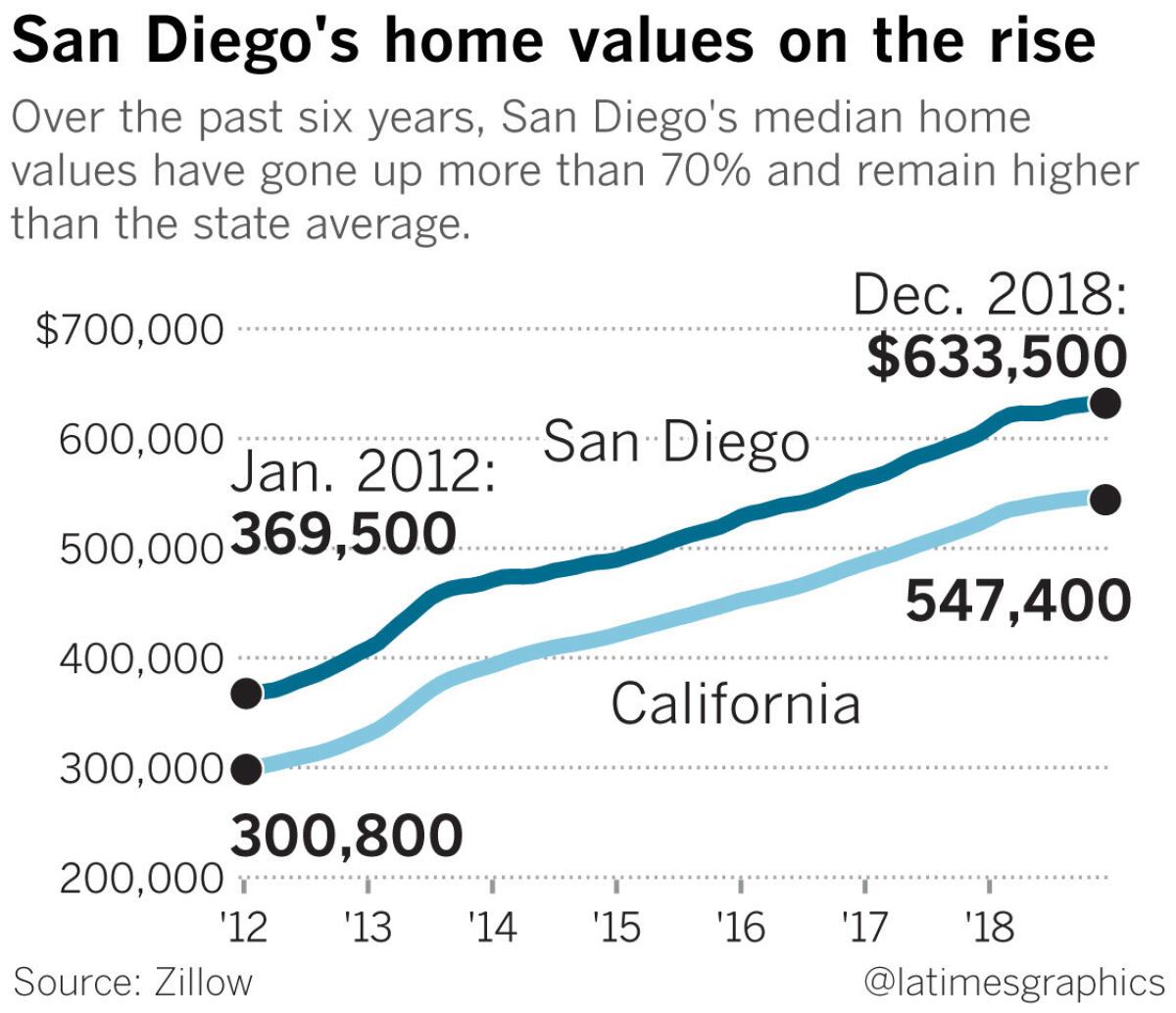

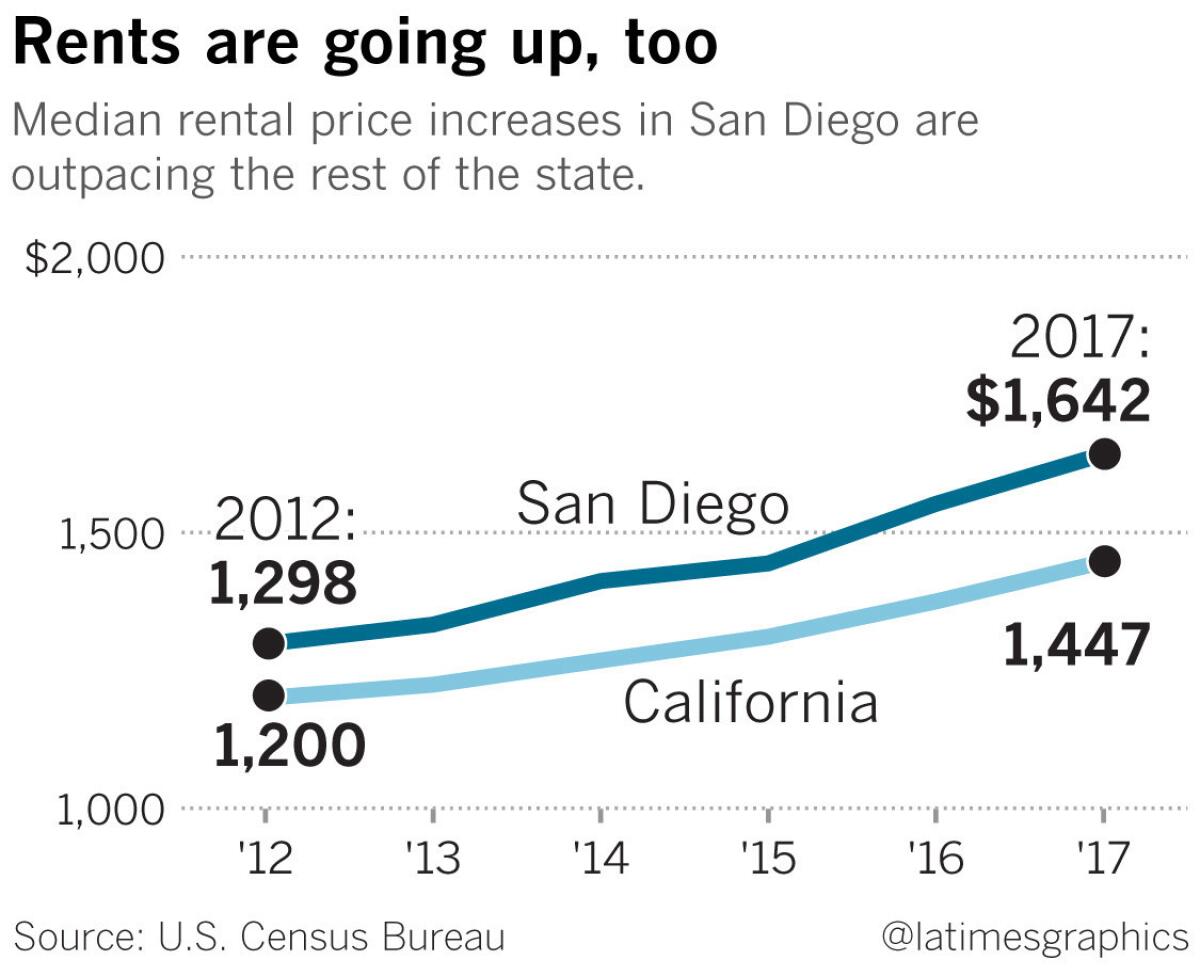

Like the rest of the state, San Diego has seen dramatic increases in housing costs. In just the last six years, median home values in the city have gone up more than 70% to $633,500, according to the real estate website Zillow. Rental prices have also steadily increased over a similar period with the median cost now $1,642, according to U.S. Census data.

The price surge prompted Faulconer to change his mind about some of the city’s rules.

Years ago, the mayor was such a staunch supporter of height limits — which control what type of developments are built — that he laughed at the idea they could make housing less available for people who want to live in San Diego. Now, he wants to get rid of height limits for apartment and condominium projects within a half-mile of transit stops. (The mayor’s plan wouldn’t apply along the coastline, where voters have enshrined a 30-foot height limit in the city charter.)

Faulconer has also proposed doing away with requirements that developers include parking with projects in areas near transit, rules city officials now estimate drive up costs by as much as $90,000 per spot. And Faulconer wants to relax limits on the number of homes that can be built on sites near transportation hubs.

By getting rid of these restrictions, Faulconer said, developers will build more homes for people of all incomes.

“You either have a housing crisis or you don’t,” he said. “We know that we need to increase our ability to produce housing that San Diegans can afford. So let’s act like it.”

San Diego, California’s second-largest city, is one of the few urban areas where Republicans like Faulconer retain considerable political power. But the mayor and City Council President Georgette Gomez, a Democrat, agree on the need for more growth, a perspective shared by council members from both parties. During a City Council meeting last month, Gomez chided a developer for proposing a project she believed was too small.

The proposals in San Diego coincide with the governor’s recent efforts to reward cities that make it easy to build and punish those that don’t. Last month, Newsom authorized a lawsuit against the Orange County city of Huntington Beach over state requirements to zone land for housing and on Tuesday the governor warned elected officials from nearly two dozen cities that they could be next.

Newsom also recently named Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg to lead a new commission on homelessness in a sign of support for the city’s approach to housing.

Steinberg, a former leader of the state Senate, said many local officials fiercely protect their control over development from state incursions. But he said that approach is the wrong one if city and county officials don’t use their power to tackle housing affordability.

“Cities should be doing more of these things on their own,” Steinberg said. “That’s the way it should be.”

In San Diego, resistance to Faulconer’s plans — which are in various stages of approval — is bubbling. Three trolley stops are under construction in neighborhoods surrounding Mission Bay and residents have fought for years against relaxing nearby height restrictions.

On one side of the trolley is Interstate 5 and the bay. On the other, car dealerships and one- and two-story businesses line a commercial corridor. An abandoned department store sits next to one of the new trolley stations, and a developer has discussed using the site to build 1,700 new homes in buildings up to 90 feet tall. A few blocks inland, single-family homes rise along a broad hillside.

In front of some of those homes are lawn signs that read “Raise the Balloon,” referring to a slow-growth group founded in 2014 by Bay Park resident and Realtor James LaMattery. LaMattery said he was astounded that the city was considering allowing taller buildings in his neighborhood and convened protesters to lift a 10-foot-in-diameter red helium balloon over five stories high to show how residents’ views would be affected.

“It was like raising the American flag,” said LaMattery, 66.

In making his pitch for growth, Faulconer has branded himself a “YIMBY,” which stands for “Yes in My Backyard,” a national movement agitating for more development that is led primarily by young professionals.

LaMattery takes issue with those who would label him the opposite: a NIMBY, or “Not in My Backyard,” for being against some forms of development.

In an email to supporters last year, LaMattery wrote that NIMBY “sounds hauntingly familiar to other classes of people that suffer institutionalized discrimination. This ‘N’ word should be added to the protected classes in anti-discrimination bills and removed from governmental documents.”

Asked about the email, LaMattery said it was “probably inappropriate” to compare the term to a racial slur. But he maintained that NIMBY was a derogatory term for those who are simply attempting to shape their communities.

Faulconer’s plan would do away with the height limits that LaMattery’s group has worked to protect. LaMattery said the resulting development would be out of scale with the rest of the neighborhood and would unalterably change the city for the worse.

“There’s going to be a huge battle,” he said. “A lot of San Diegans believe this is just a lot of L.A. development coming in.”

While community groups reacted immediately when Faulconer introduced his plan at the State of the City, political leaders did not. The lack of response stunned Cory Briggs, a prominent local environmental attorney, who then decided to run for mayor in 2020 on a platform against aggressive growth.

Briggs said Faulconer’s proposal would run roughshod over neighborhood planning and lead to the construction of expensive developments unavailable to those who aren’t wealthy.

“There’s no housing crisis,” Briggs said. “There’s a workforce housing crisis, an affordable housing crisis.”

Academic research indicates that new supply makes housing more affordable across a region, but that might not happen in individual neighborhoods when zoning rules are relaxed.

Gomez and Faulconer don’t have exactly the same beliefs on housing and seem headed for a clash over what percentage of development must be reserved for low-income residents if height limits go away. The mayor’s initial plan calls for no change to the city’s current rules that can require 10% of a project to be for low-income residents. Gomez thinks that percentage should be higher.

“If we are amending the regulations, what are the benefits?” she said. “I don’t want to support a project that is market-rate and have it just be market-rate. Because we’re not addressing the need for people living in the streets.”

Despite this divergence, city leaders remain in favor of new building — even in the face of inventive protests.

Dozens of residents living near a proposed 20-story apartment complex next to the city’s Balboa Park dressed in all black and held up black umbrellas on a playing field that they believed would be covered in shadows if the towering development were approved. The idea came from a successful protest spearheaded by former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in the late 1980s in New York City against a development that would have shaded an area of Central Park.

The council met for nearly two hours to debate the development three weeks ago. It was approved unanimously.

Twitter: @dillonliam

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.