Despite warnings of fraud and a rigged election, America’s polling places saw no major disruptions

Reporting from Philadelphia — After a dark presidential campaign, roiled by warnings of widespread voting fraud and intimidation, hundreds of Justice Department and other lawyers stood ready Tuesday for a stormy election day.

For the most part, they didn’t get it.

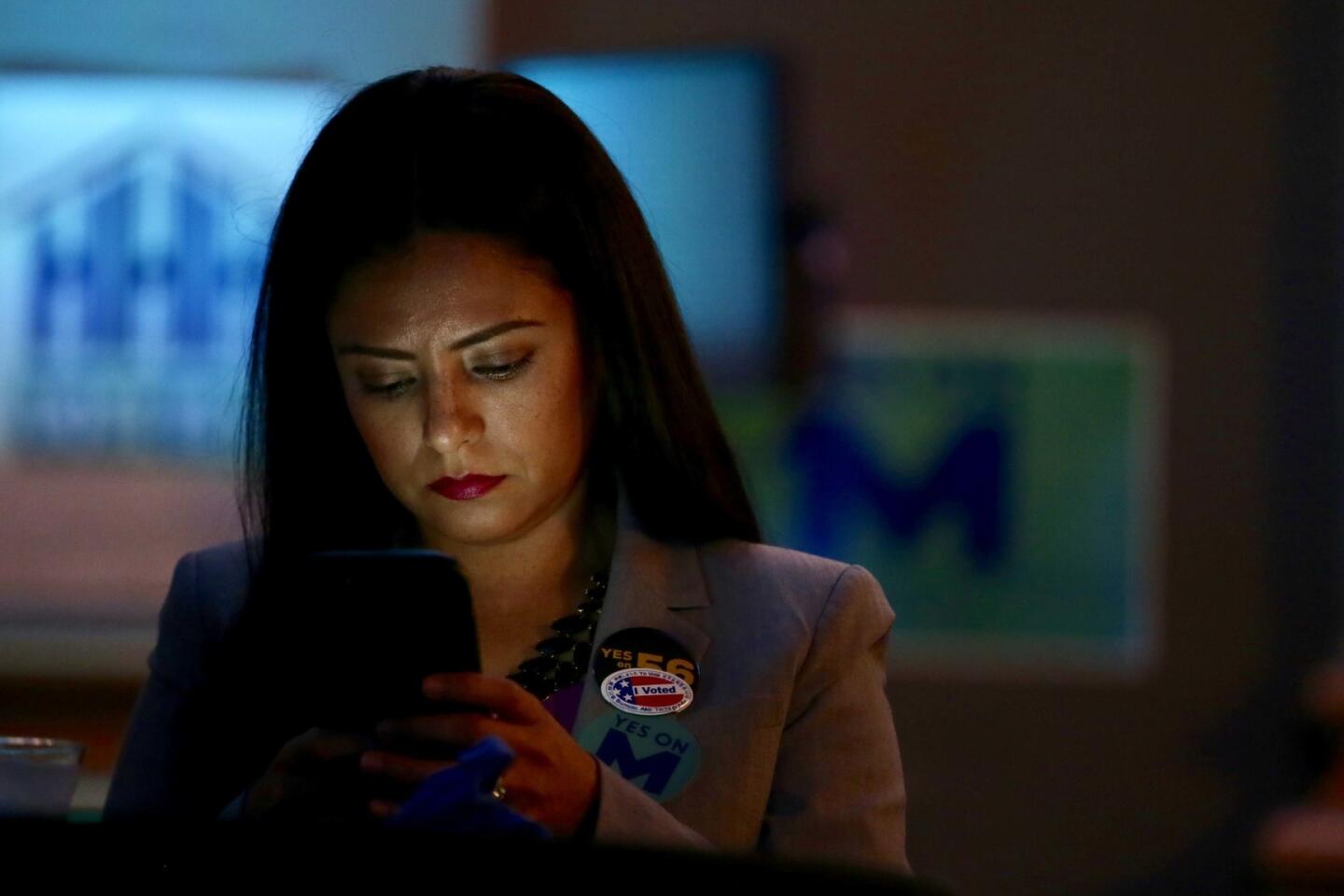

With tensions high, more than 30,000 calls about malfunctioning machines, alleged voter intimidation and other problems poured into a hotline set up by a coalition of civil rights and legal aid groups.

Callers complained of signs put up to scare black voters in Ohio, of faulty voting machines in North Carolina and other states, of arguments and snubbed voters in Florida, and of late-opening polling places and other snafus in Philadelphia.

But as the day wore on, sunny and warm over much of the country, there was little out of the ordinary.

In Broward County, Fla., police were called after a scuffle broke out between two election clerks, and they were fired. In Los Angeles County, a shooting left one person dead near a polling place in Azusa. The county registrar told voters to avoid the area and go to alternative polling stations.

In Fort Bend County, Texas, the sheriff’s office said it arrested a man who tried to vote twice. “Claimed he worked for Trump and was testing the system,” the sheriff’s office tweeted.

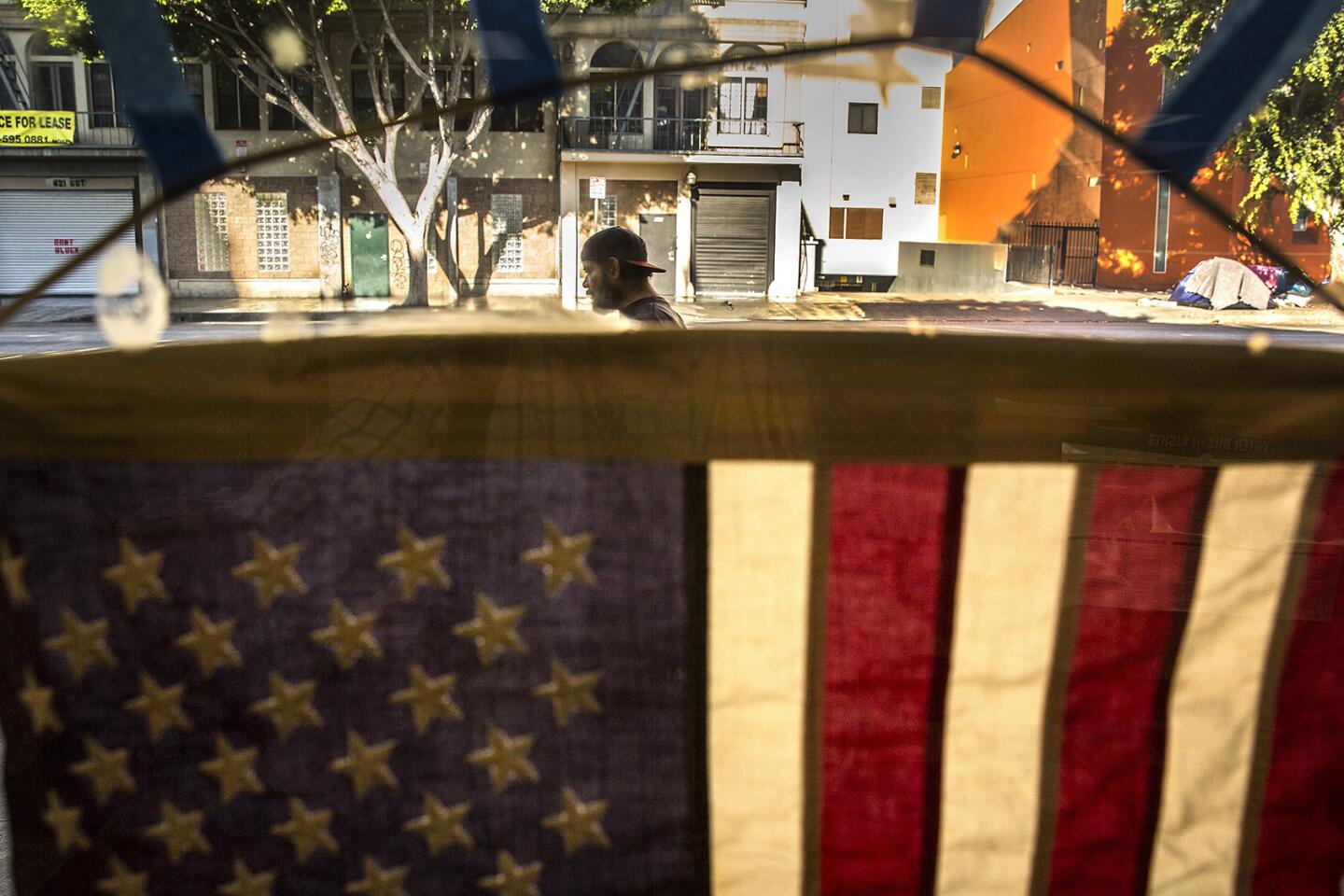

In African American neighborhoods in overwhelmingly Democratic Philadelphia, a city Donald Trump had repeatedly called a nest of voting fraud, there was no army of his rural supporters outside polling places, as local officials had feared.

“We have no founded complaints of intimidation, no founded complaints of voter fraud, and we have no apocalypse of zombies voting all over town,” Dist. Atty. R. Seth Williams said at a news conference.

Several hundred men volunteered to stand outside polling places in African American neighborhoods to watch for trouble from outsiders — and didn’t find much, if any.

“My job is to make sure there’s no disturbance when people come to vote,” said Howard Walker, 76, a deacon at Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, outside a polling place in the Mount Airy neighborhood. “I don’t see that really happening.”

That appeared to be the case elsewhere around the country.

“We’re seeing various kinds of complaints, from police officers being too close to the polls to overzealous partisans,” said Myrna Perez, a lawyer from the New York-based Brennan Center for Justice who joined an Election Protection legal aid project that involved dozens of civil rights groups.

Perez reported scattered complaints of attempted voter intimidation but no sign of a “concerted” campaign.

Kristen Clarke, president of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, said Election Protection lawyers logged a “substantial” number of complaints from Florida, including an “aggressively assembled” group outside a polling site in Hollywood, north of Miami.

In Palm Beach County, some students at Florida Atlantic University were told they could not vote because their dorms didn’t count as a legal address; they were given provisional ballots, Clarke said.

“We’re going to dig into all these reports more closely and carefully,” Clarke said. “But most importantly, we want to ensure that voters are able to cast a ballot free from intimidation or harassment, which requires making sure that unauthorized people are not inside our polls today.”

Homeland Security Department officials reported no sign that computer hackers had attacked polling systems at the nation’s 9,000 voting districts.

That fear had grown after a campaign that, U.S. intelligence officials say, saw Russian-backed hackers steal and leak thousands of emails from Democratic officials, including Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager, in an effort to interfere with the election.

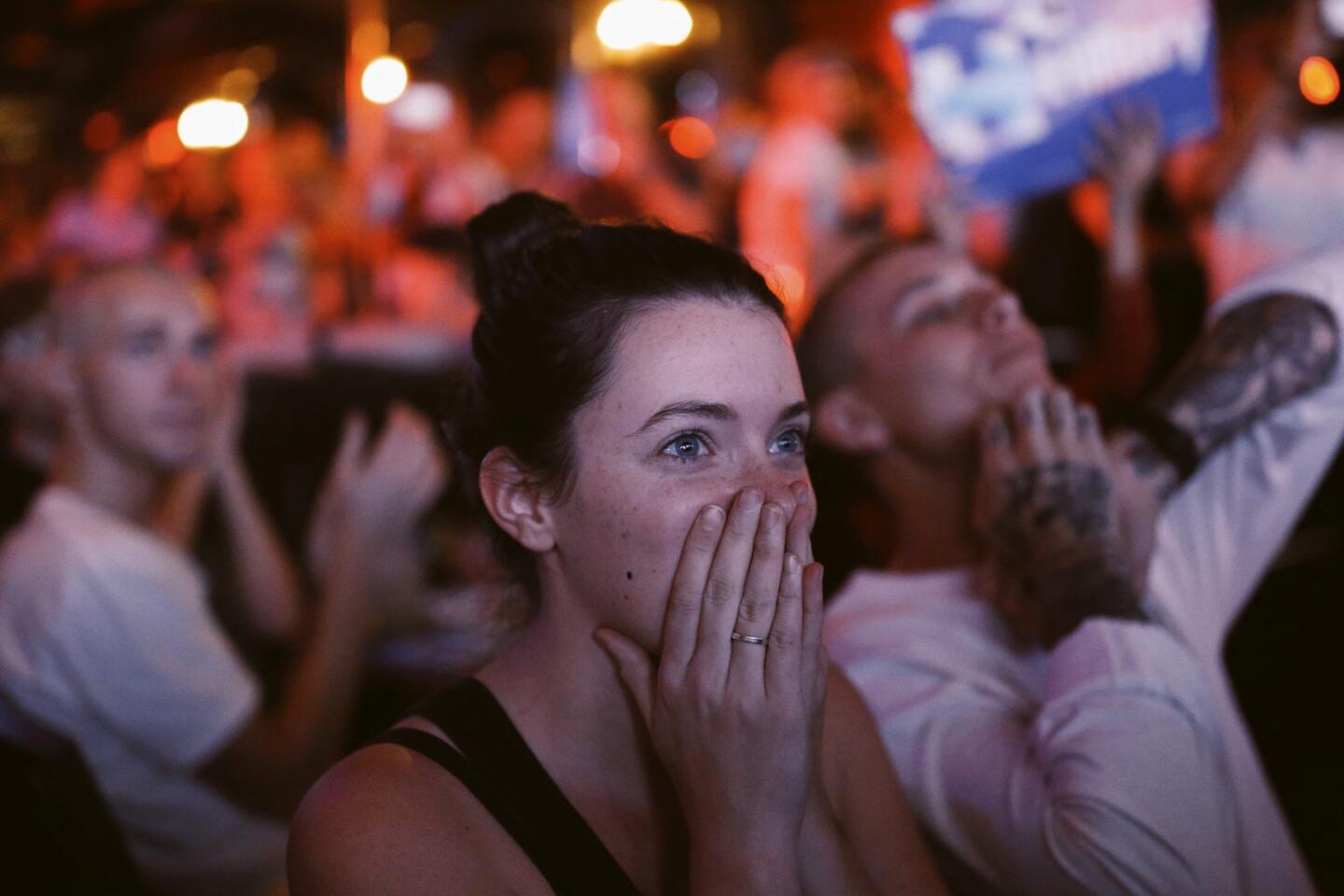

Long lines and voting machine glitches were common, a regular problem in a nation with aging election machinery.

Broken or balky machines were reported in Utah, New York, Illinois, Kentucky, Texas, Virginia, Ohio, Connecticut and especially North Carolina.

Electionland, a voting monitoring project, reported glitches with optical scanners in seven counties in North Carolina. The state elections board instructed Durham County officials to use paper ballots instead and extended closing time at several polling places.

Officials in Dover, N.H., also extended voting hours after an email sent the wrong poll information to voters there.

Civil rights groups reported confusion in Alabama and other Southern states with new voter ID requirements since the last presidential election. In some cases, voters did not realize their polling locations had changed since 2014.

“Voters were confused because of changes to their polling places and a lack of accurate information provided to them by their state officials,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

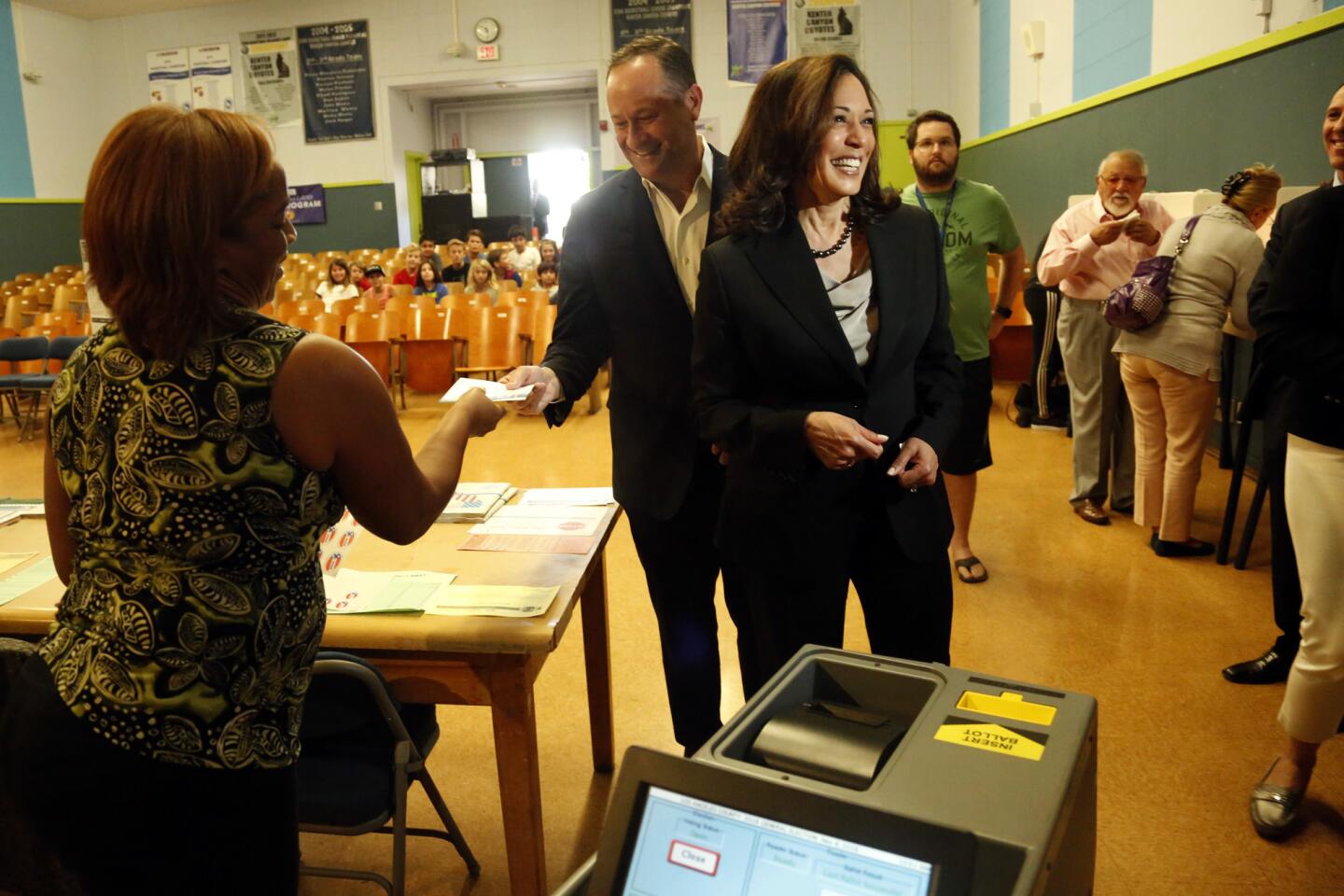

Trump filed his own lawsuit Tuesday in Nevada, saying polls were wrongly kept open late during early voting in the Las Vegas area, where Clinton had strong support. Nevada law says polls should stay open for eligible voters already in line at closing time.

At a hearing, District Judge Gloria Sturman rejected a request by Trump’s attorneys for the names of paid and volunteer poll workers at the locations where Trump alleged improper after-hours voting took place.

“Do you watch Twitter?” Sturman said. “Have you watched any cable news shows? There are Internet – you know the vernacular – trolls who could get this information and harass people. Why would I order them to make available to you information about people who work at polls?”

Problems on election day are common, but Trump turned those concerns into a keystone of his unconventional campaign, warning for weeks that voting would be “rigged” against him.

Twitter: @jtanfani

ALSO

Live election updates on Trail Guide

Voter voices: America’s state of mind on election day

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.