Do Americans hate each other too much to find common ground?

- Share via

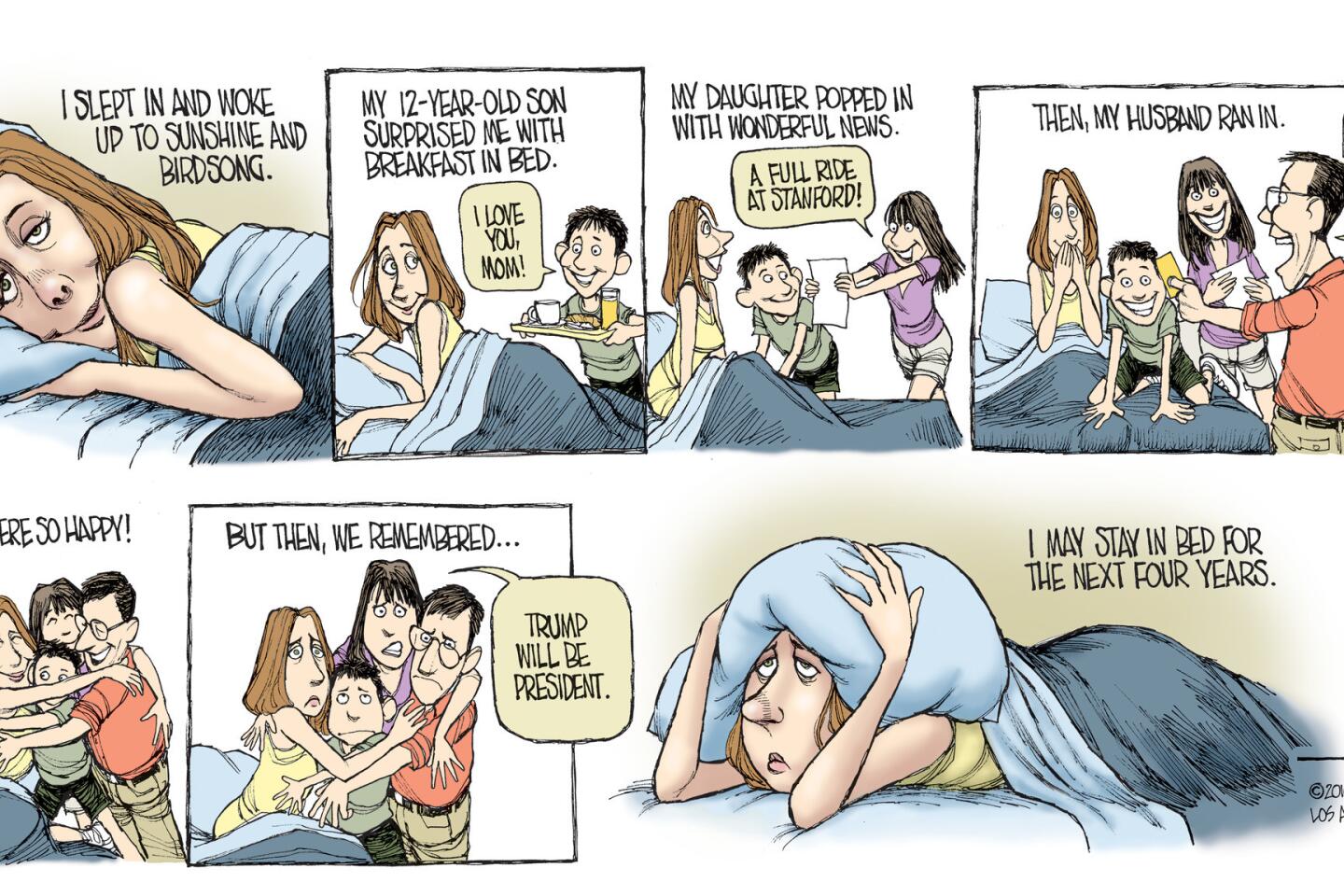

In early December, a wildfire raged through the Great Smoky Mountains and destroyed nearly 1,000 homes in Gatlinburg, Tenn. Thousands were evacuated. Close to 200 people were injured or made ill by the blaze. Fourteen were killed.

In the midst of this tragedy, numerous messages appeared on social media that were as despicable as they were dispiriting. One man sent out a tweet that said, “Laughing at all the Trump supporters in Gatlinburg as their homes burn to the ground tonight. Too bad it’s not the whole state burning.” Someone else tweeted that “a few confederate flag flying hillbillies losing their mobile homes isn’t newsworthy.” Another suggested “maybe it’s ‘god’ punishing them for voting for Trump.”

And another seemed to think empathy for one group negates empathy for another: “Honestly? White privilege is mourning Gatlinburg while ignoring Standing Rock and I’m not having any of that s—t today.”

Obviously, as conservative commentator Zach Montanaro noted after listing many of the offensive tweets, “not all liberals feel this way. These are just a small group of nut-jobs.” Nevertheless, the “nut-jobs” who are willing to openly say these things represent a malign spirit that seems pervasive from one end of the political spectrum to the other. Far too many Americans are willing, and even eager, to think the worst and often say the worst about their fellow citizens.

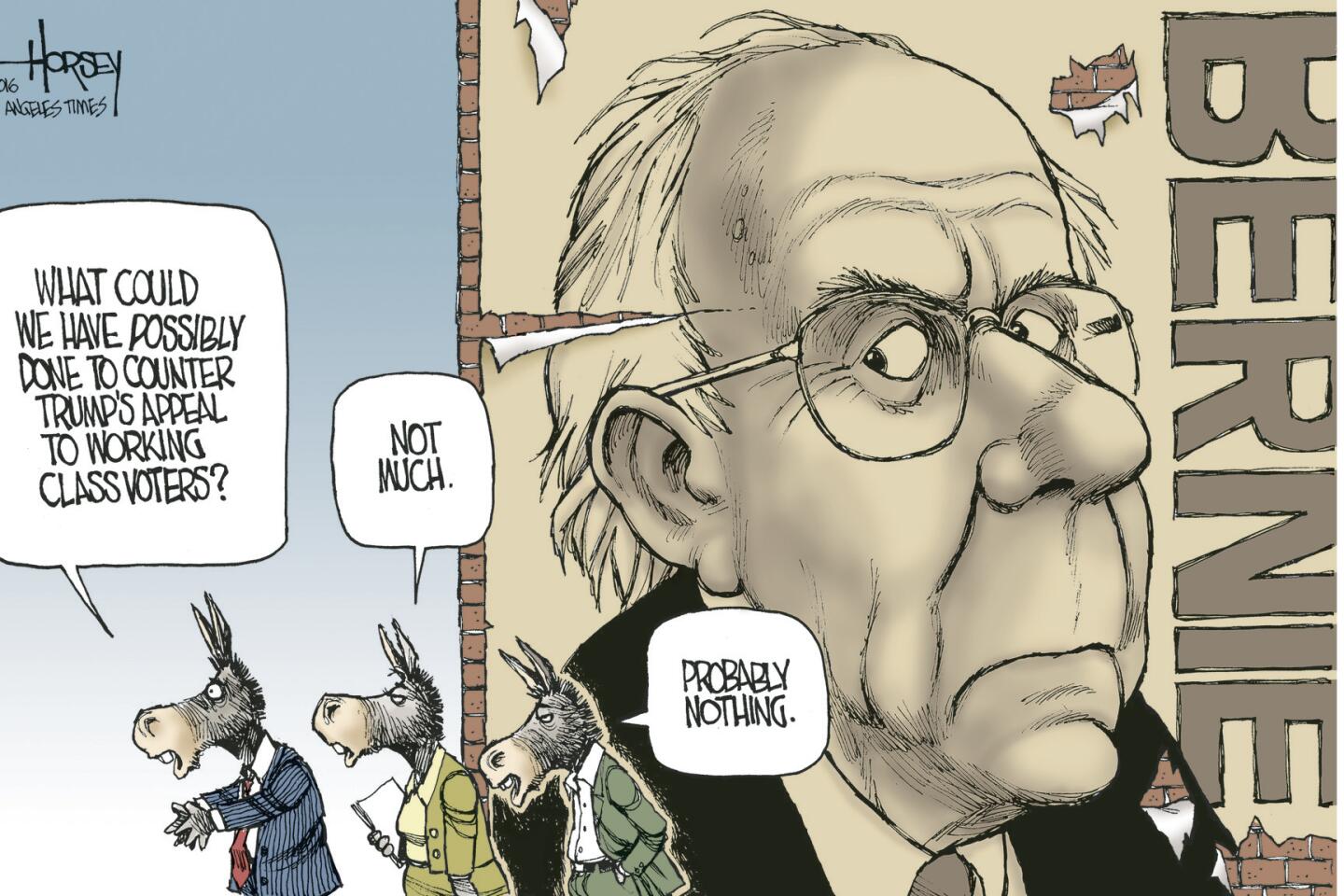

It is not just a liberal versus conservative or Republican versus Democrat thing; the level of anger and antipathy between supporters of Hillary Clinton and backers of Bernie Sanders has not abated much over the months since the Democratic nomination was decided. Still, the political madness may have reached a new zenith last month when Edgar M. Welch, an earnest young family man from North Carolina, drove to the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant in Washington, D.C., and began shooting up the place with an AR-15 rifle. His actions were inspired by a fake news story that claimed Hillary Clinton and the Democrats were running a child sex ring out of the pizza shop.

Was Welch alone in his willingness to believe such an outrageously absurd allegation against a politician and a party he did not like? Hardly. A friend with close ties to the Chinese-American community in Los Angeles tells me she has had conversations with a number of prominent, well-educated people in that community who voted against Clinton because they readily accepted as true the fake news stories about the Democratic Party nominee having sex with small children.

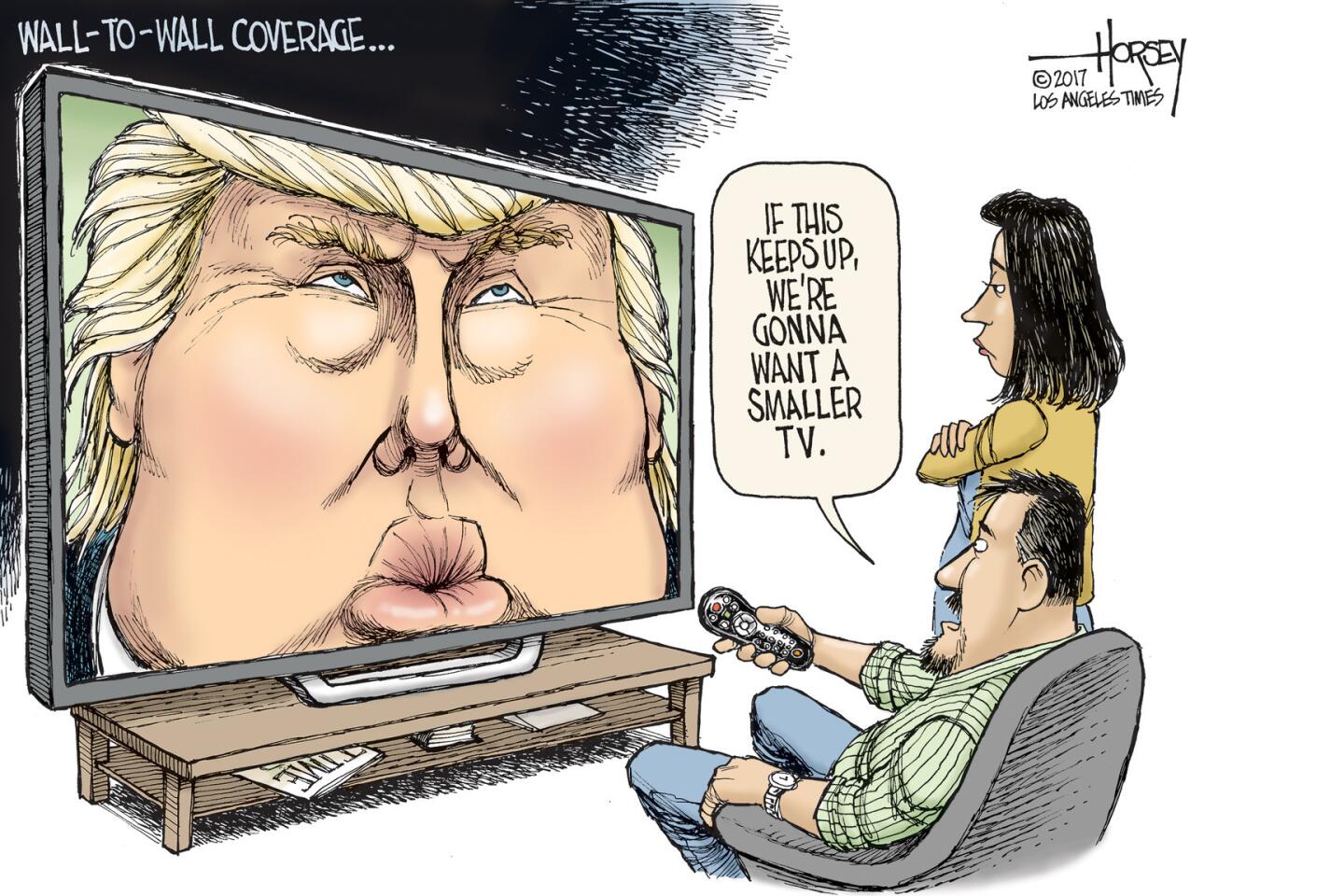

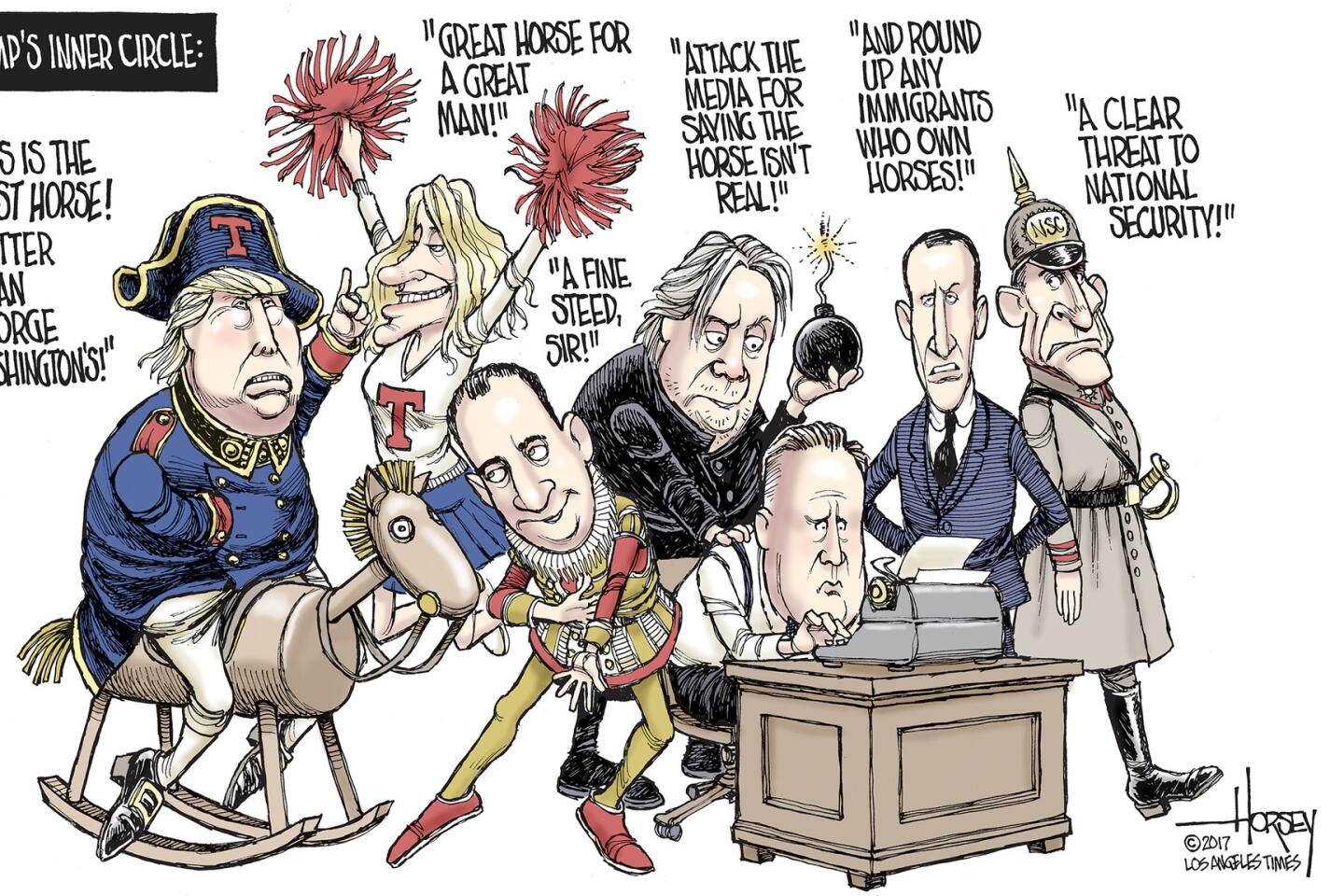

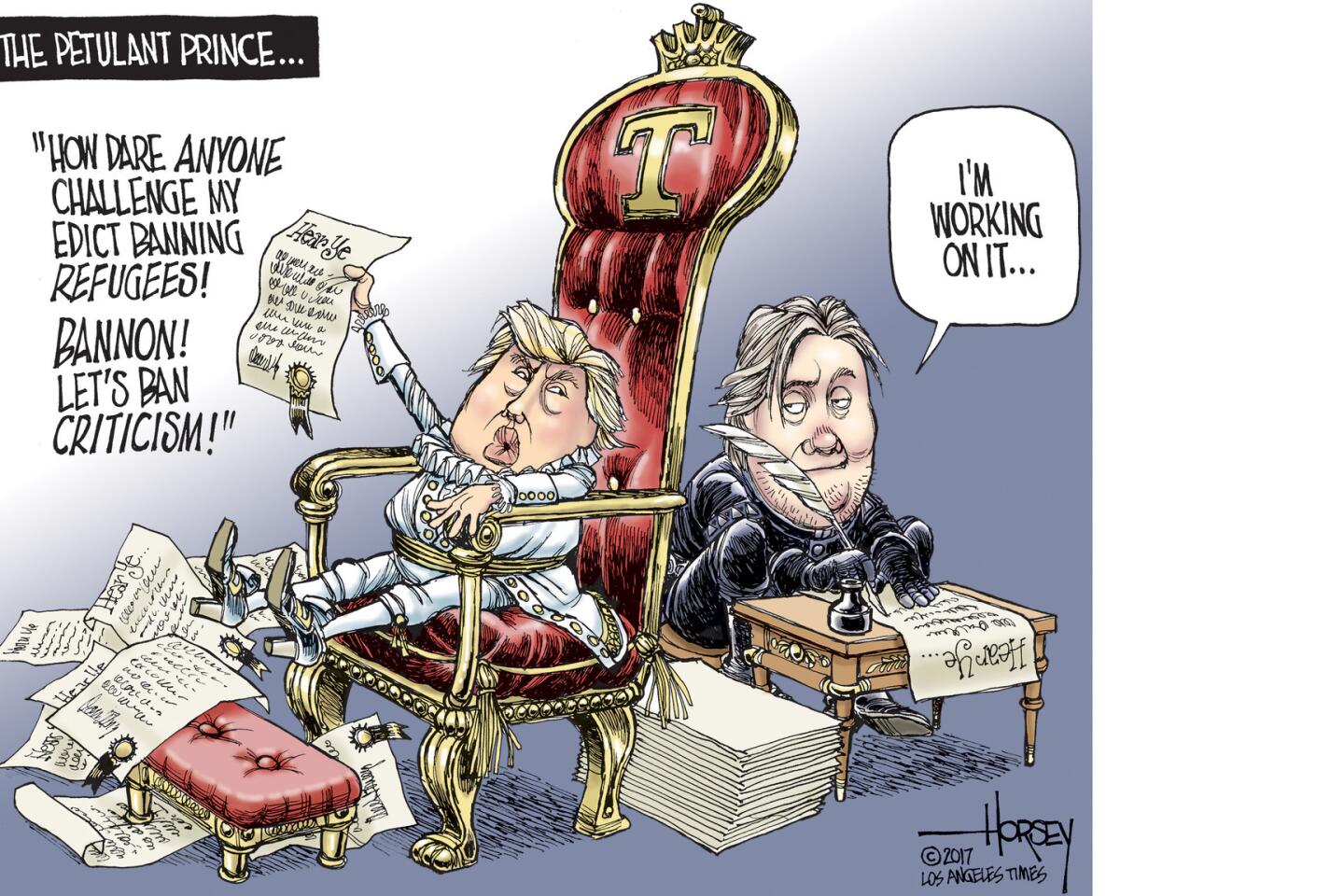

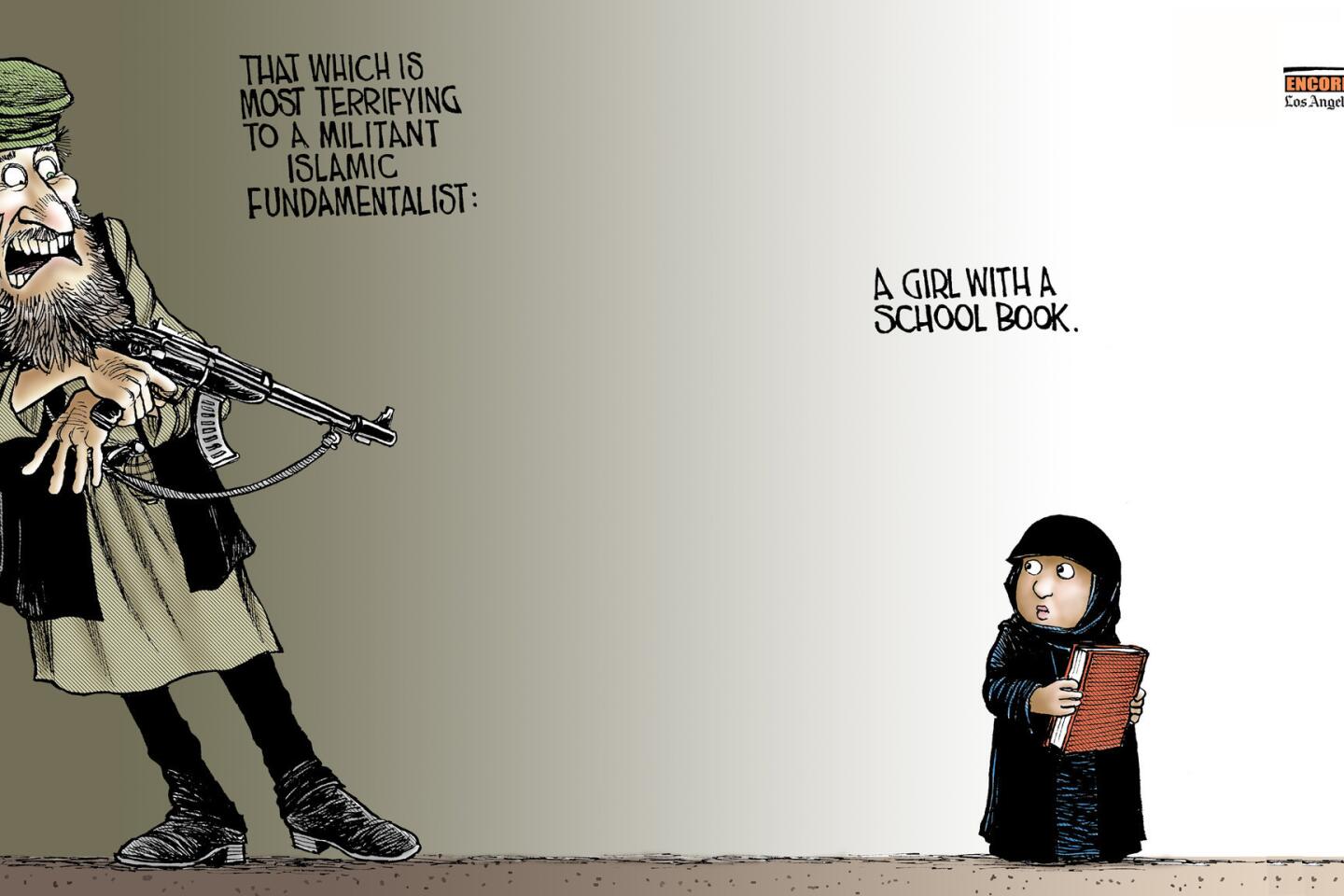

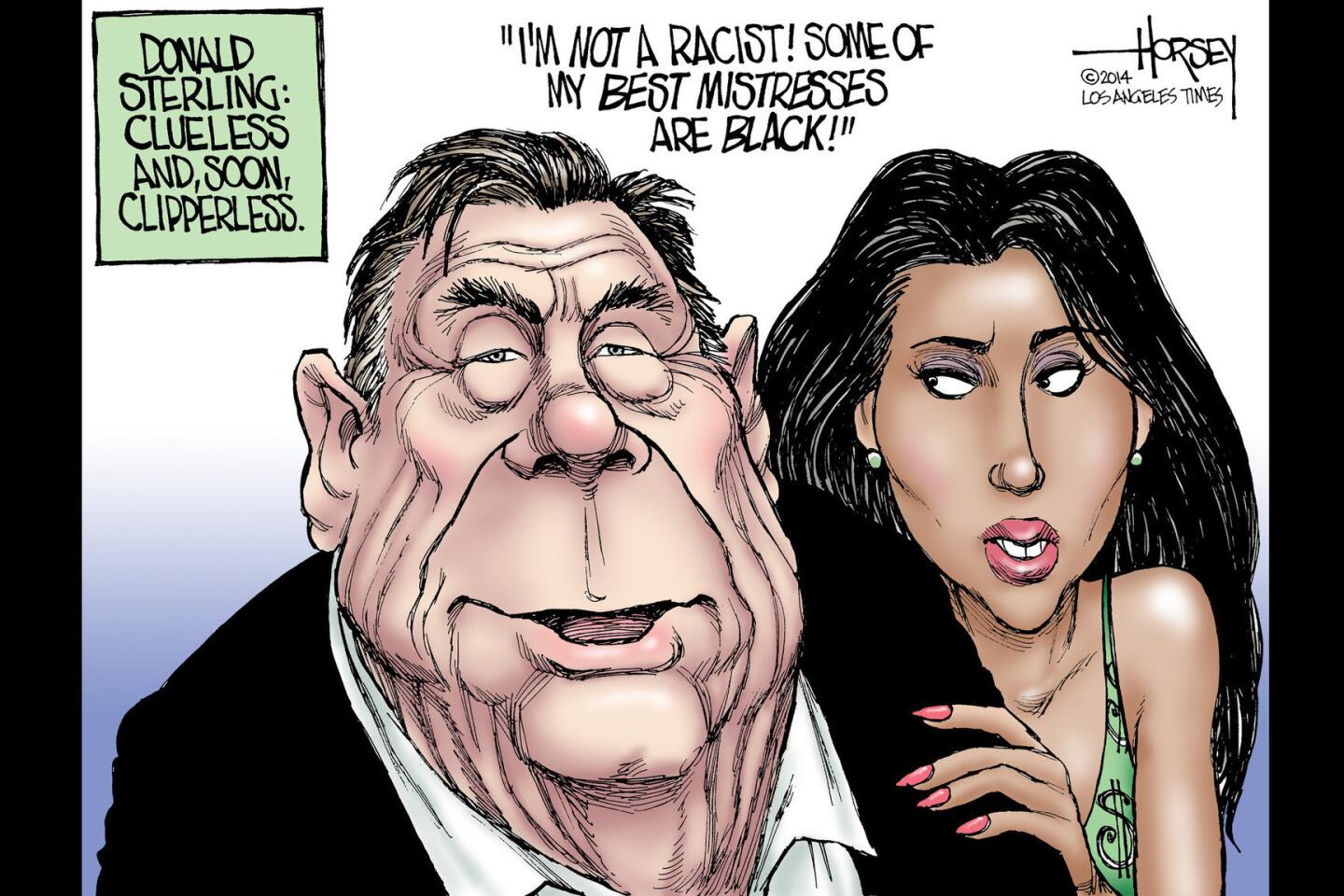

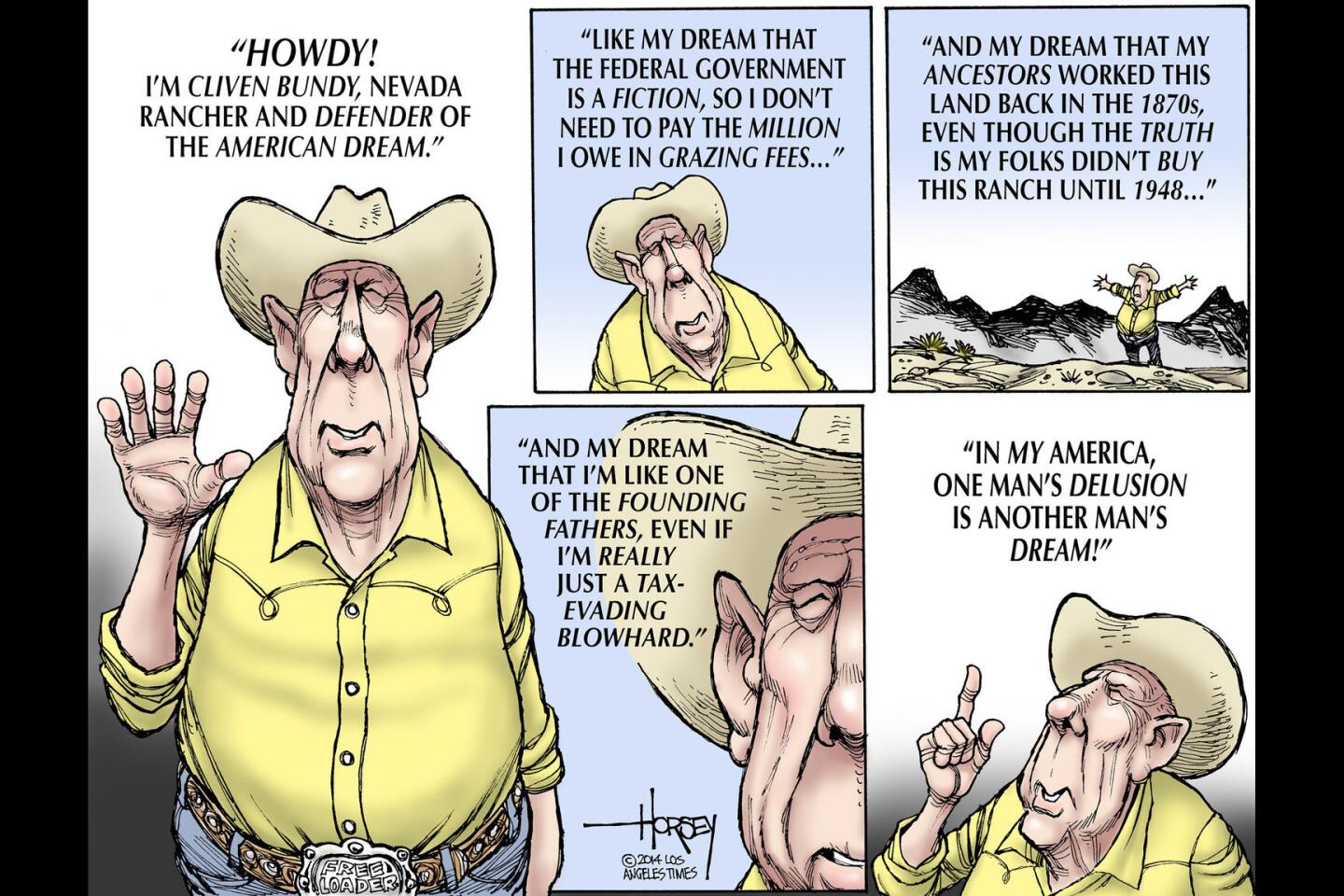

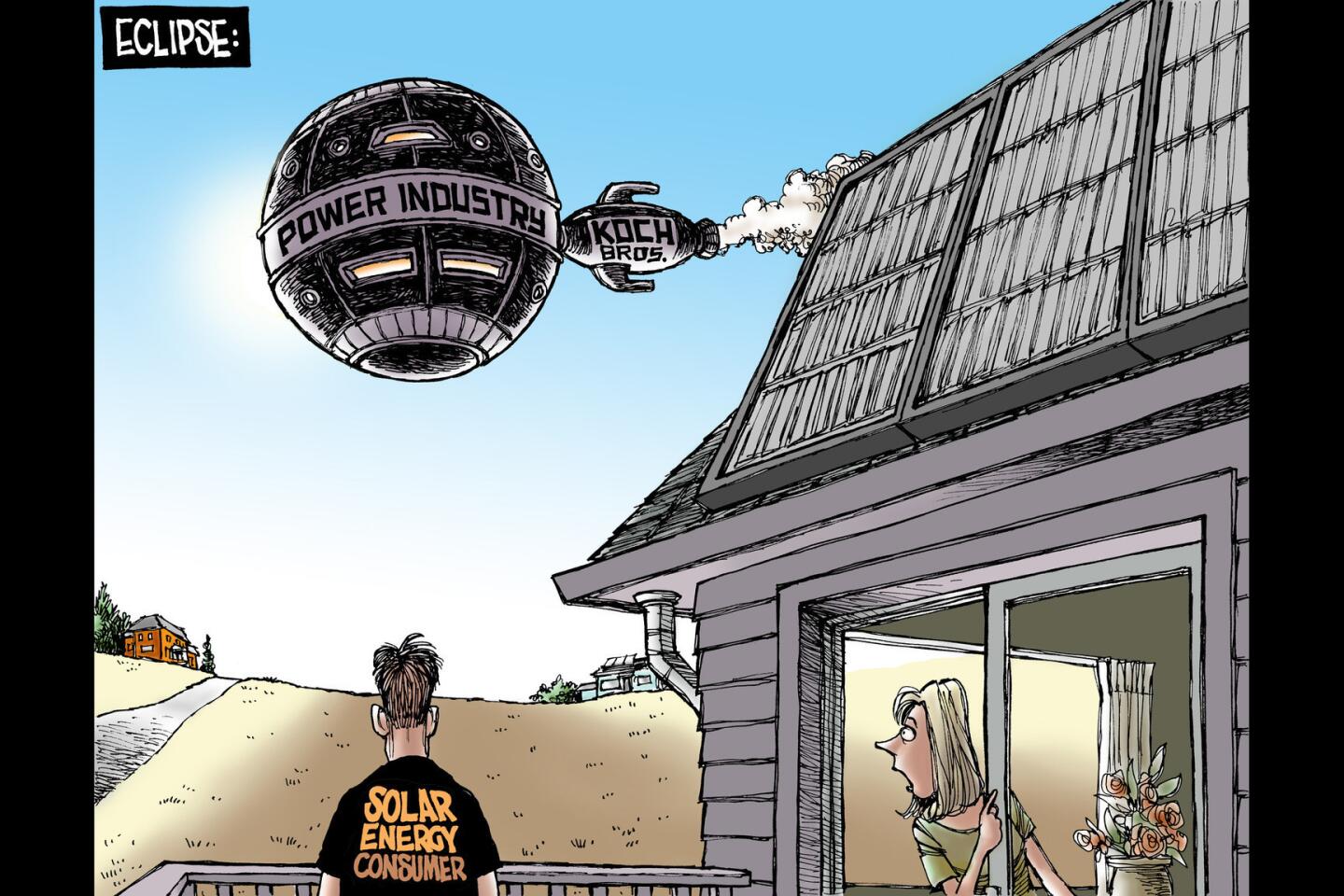

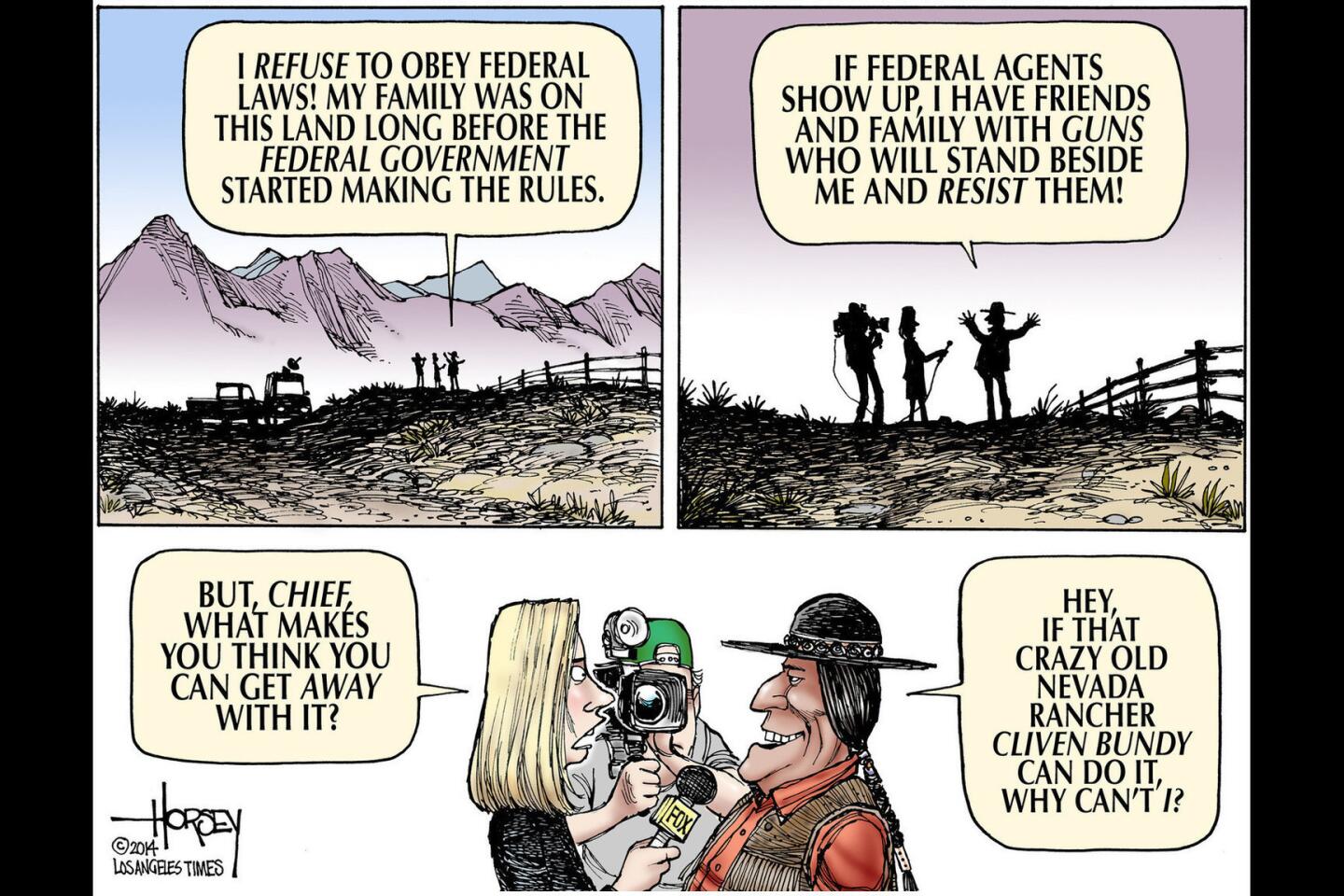

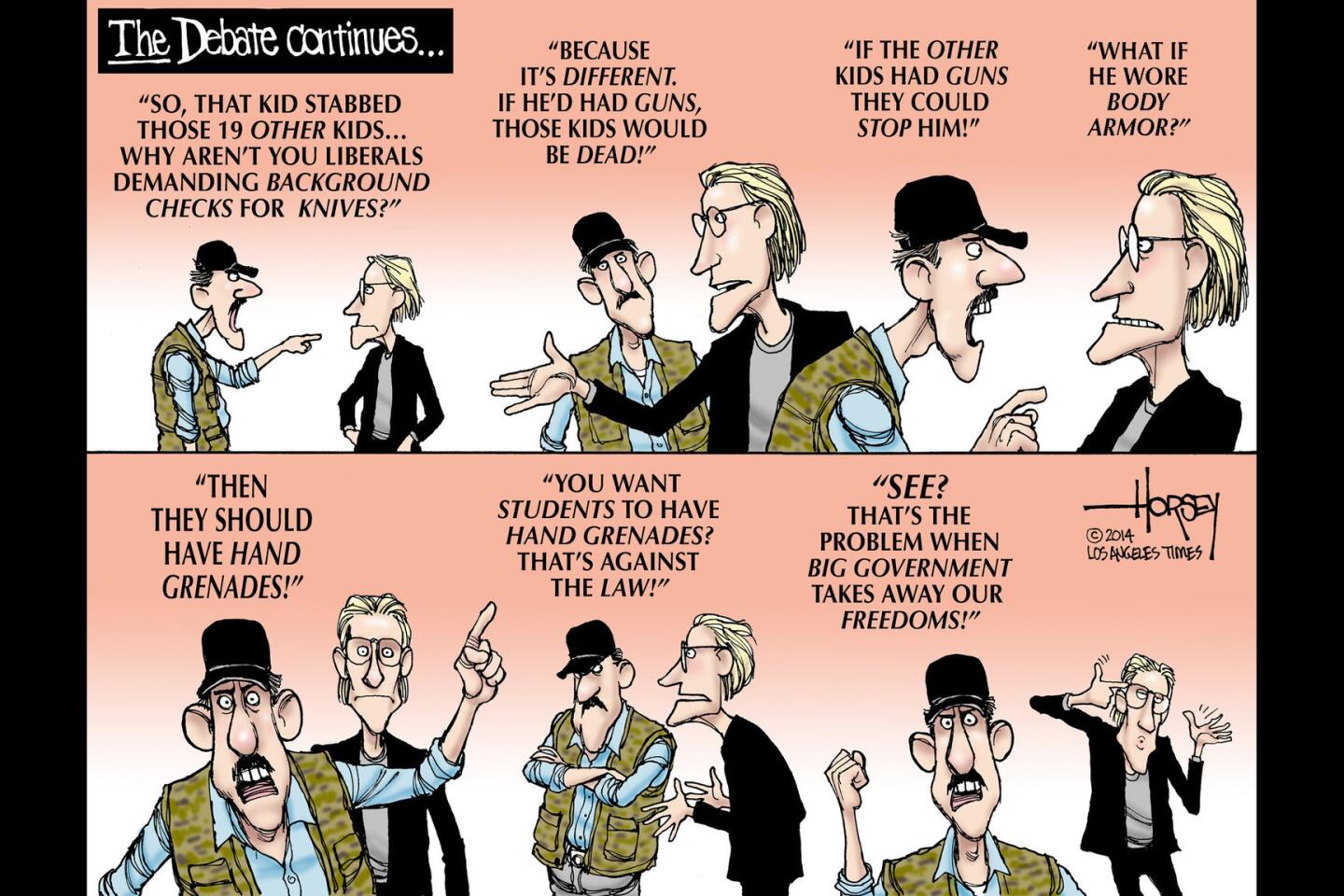

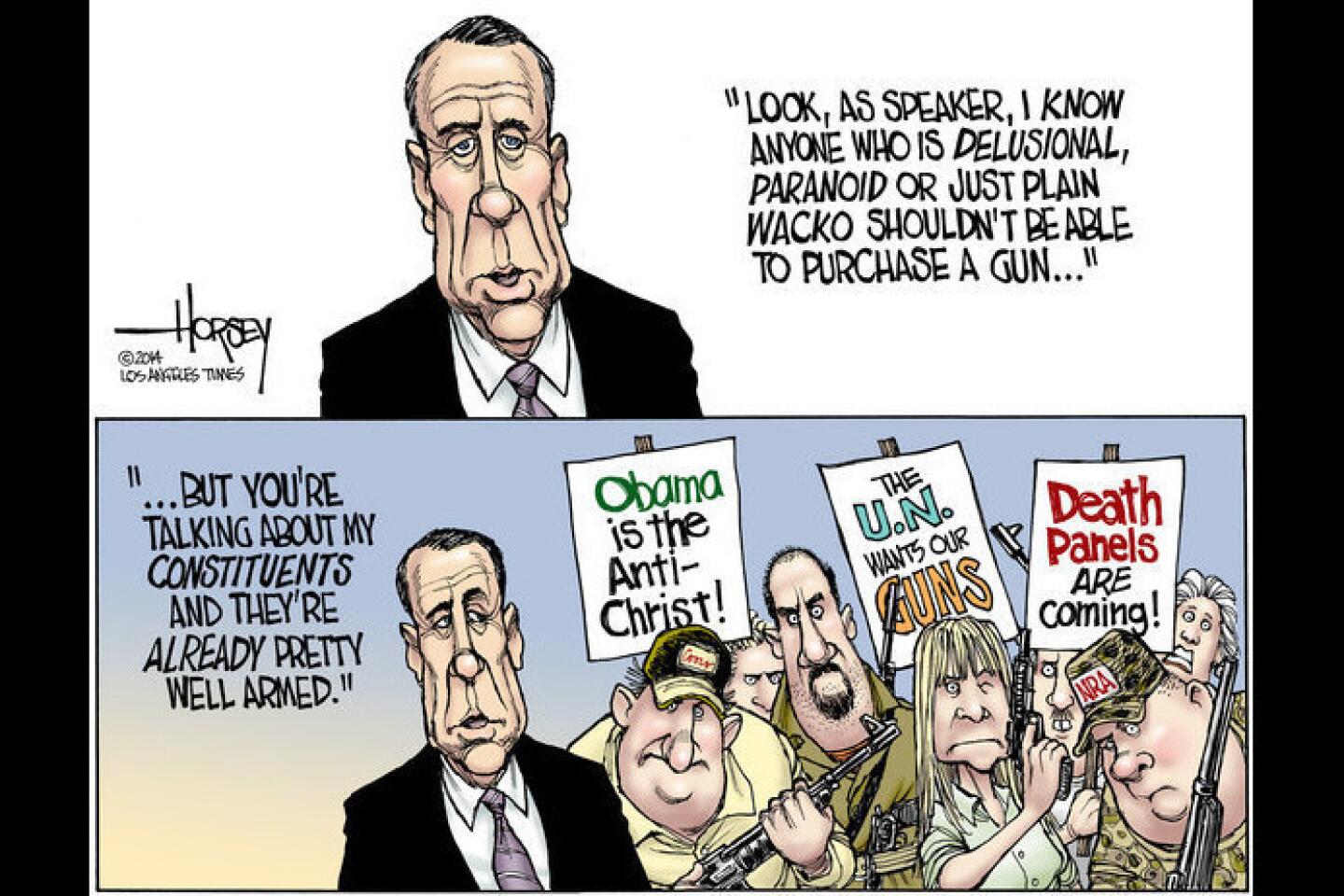

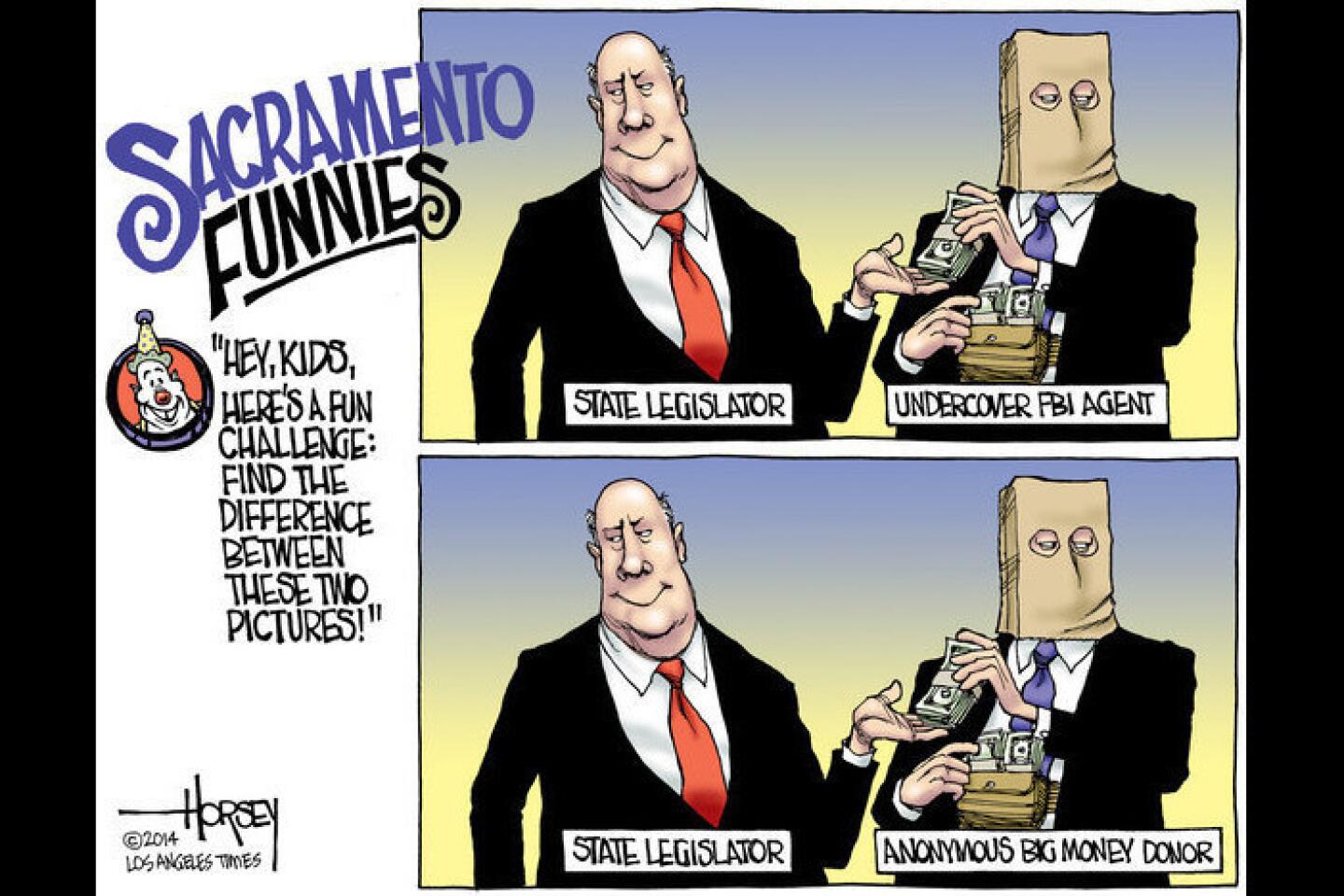

America’s toxic political climate has been fueled by these kinds of malicious, false stories spread on the Internet, as well as by talk radio hosts, bloggers and TV commentators who profit from broadcasting conspiracy theories and fomenting fear and resentment. Social media has given a very loud megaphone to those on both the left and right who want to turn healthy, sharp discourse into caustic slander. Has all of this changed the way Americans perceive each other, or have such hateful feelings always been a part of who we are?

Responding to one of my recent columns, an American expatriate in Bangkok wrote, “Americans really don’t like each other. Pretending that class and racial antipathy doesn’t exist is a Pollyanna understanding of how society really is.”

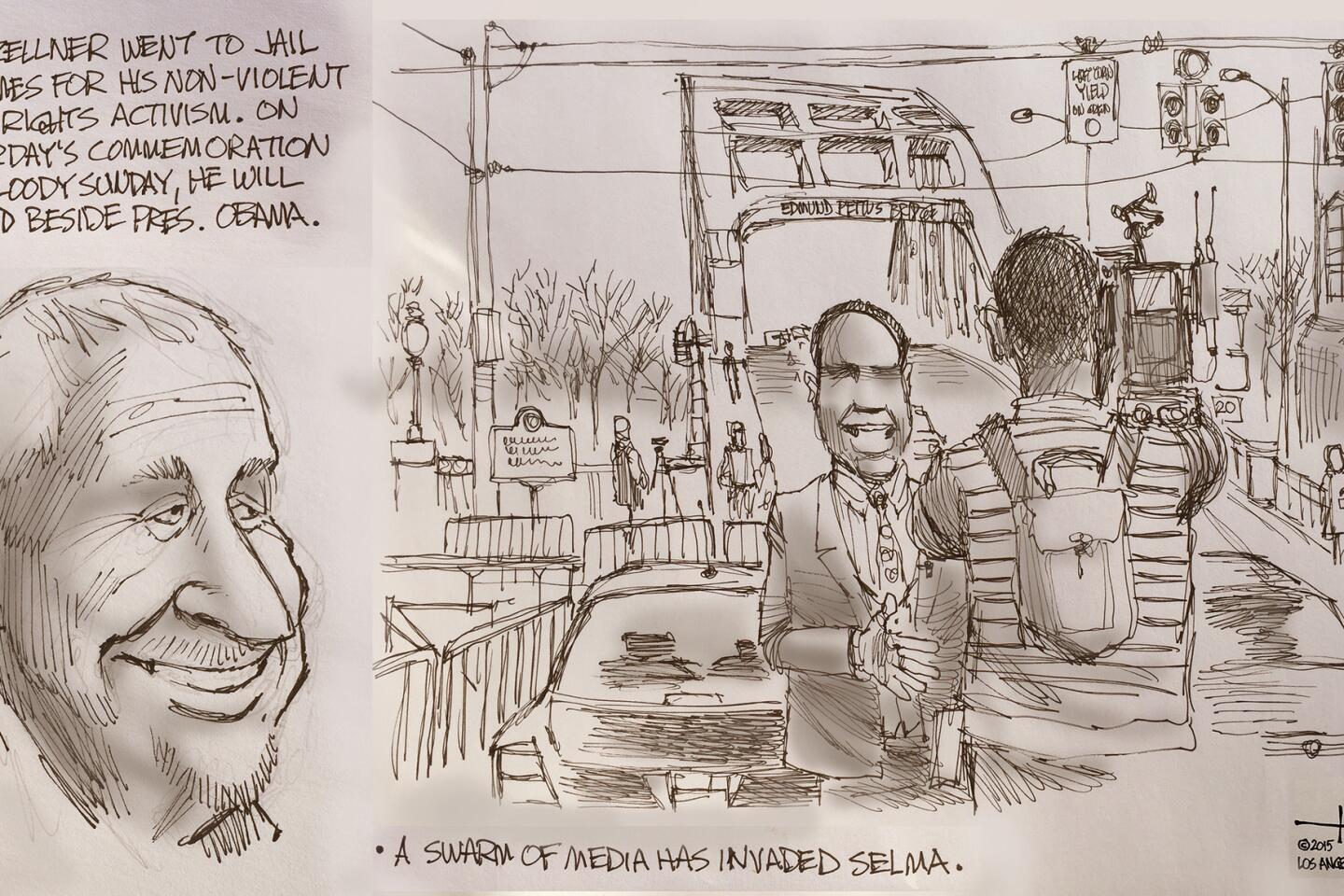

It is not hard to find plenty of evidence throughout this country’s history to back up that view, from the Civil War to the civil rights movement, from bloody clashes over workers’ rights to pogroms against Irish immigrants in the East and Chinese and Japanese immigrants on the West Coast. We have fought each other about as often as we have pulled together, and the impulse toward separating so-called real Americans from those we do not consider authentic gets passed from generation to generation. A disturbing example of this occurred the Wednesday after election day when white students at Royal Oak Middle School near Detroit began chanting “build a wall!” as two Latino girls — both U.S. citizens — entered the school lunchroom.

I have always chosen to believe that, when it comes down to it, whatever our differences may be, we all stand together as Americans. Am I wrong? One reader sent me a note recently saying that, when he looks at liberals and urban blacks and immigrants, he sees people with whom he has “absolutely nothing in common.” Is the divide really that deep? Judging by those who so quickly seized on the Gatlinburg tragedy as a chance to vilify suffering people for no good reason but politics, maybe it is.

Still, what I do know is that, in all the many times I have traveled to different parts of this country, I have met good people everywhere — people of every political persuasion, of every religion (or no religion), every ethnicity and every race — people with whom I always find common ground. What seems to be disappearing is our commitment to find common ground in our political life.

Perhaps we need to learn from Michael Reed, a man who lost his wife and two daughters in the Gatlinburg disaster. Reed wrote an open letter offering forgiveness to the two adolescent boys who were arrested for starting the wildfire.

“As humans, it is sometimes hard to show grace,” Reed wrote. “We hold grudges. We stay angry. We point the finger and feel we have to lay the blame somewhere. It’s human nature and completely understandable. But I did not raise my children to live with hate. I did not teach my girls or my son to point the finger at others.”

I do not know who Reed voted for in the presidential election. I do know he is an example for all of us, an example we need to emulate if we want to have a republic that is worth keeping.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.