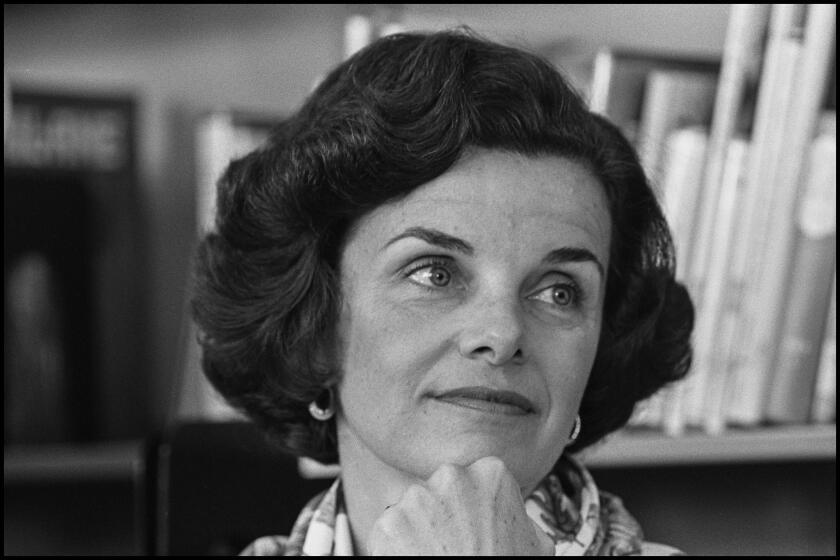

Commentary: The week I spent with Dianne Feinstein in the eye of the 2003 recall storm

One day during the first week in August 2003, I was sitting outside a conference room at the Aspen Institute in Aspen, Colo., waiting for Sen. Dianne Feinstein to emerge from a seminar on violence in the Middle East.

I was there to shadow her and get the scoop if she suddenly decided to dive into the 2003 race to recall California’s unpopular Democratic governor, Gray Davis. She had run unsuccessfully for governor in 1990, but by this time, she had been a senator for more than 10 years, rising in the ranks of seniority. Whatever her decision, she would have to make it by the filing deadline on Saturday. It was Tuesday.

I thought I was on a fool’s errand, and she would banish me as soon as I announced I was there. As I sat waiting for the seminar to end, I scanned an itinerary someone had left behind. Participants included academics, journalists, government leaders — and Queen Noor of Jordan. The day’s events were to end with a buffet dinner at Feinstein’s spectacular ranch in Aspen.

Key moments in Dianne Feinstein’s boundary-breaking career in California politics

The doors opened and people streamed out. There was Feinstein. I went up to her and told her why I was there. “I heard you were coming,” she said calmly. (I had talked to one of her aides.) I was surprised she seemed fine with the idea of me following her around. Maybe she was flattered. Or maybe she really hadn’t made up her mind about the race.

She was under enormous pressure from Democratic power brokers to be a counterweight to the assorted politicians, civic activists and oddballs who had announced their campaigns to replace Davis if voters tossed him out.

I asked if I could come to the party at her ranch that night. I was braced for her to say no, but to my delight she immediately said, yes, you can come but don’t take notes. Within about a half-hour of my arrival, that edict fell away.

The first female California senator made a profound mark embracing progressive causes such as an assault weapons ban and damning the CIA’s use of torture.

Bear Paw Ranch, as it was called, looked like a log cabin mansion and sat on a mesa overlooking hills and greenery of the Woody Creek Valley. The senator and her husband, Richard Blum, who died last year, were both there.

Feinstein and I wandered the grounds and chatted. At 70, she was tall and striking, dressed in Versace jeans and Lucchese cowboy boots. I asked her if she ever wanted to run for president. She said, “no.” Then she added quickly something to the effect of “well, you never say never.”

Ahh. Ever the ambitious politician, I thought, wondering what she might be like as president.

California has lost its trailblazing senior senator, one of the rare congressional members who still believed in cordiality and cooperation.

Meanwhile the rest of the group at the ranch that evening was trying to imagine her as governor. Author Walter Isaacson, chief executive of the Aspen Institute at the time, looked around and said, “This is nicer than any governor’s mansion I’ve ever seen.” Feinstein’s guests laughed, but she just smiled.

“I don’t want to guilt-trip you,” Jane Harman, then a Democratic congresswoman from the South Bay and other coastal spots and a close friend of Feinstein’s, said to the hostess and her guests. “I am happy with whatever decisions you make.”

Over the next few days, Feinstein and I got a little more casual with each other. I mentioned I’d bought a necklace at a jewelry store in town. “Oh, be careful about spending your money in those stores,” she warned. “They’re too expensive.” Her tone was all protective mom.

On that Wednesday morning, her office put out a statement announcing she would not run. “Morally, ethically, is it the right thing for me to get into the race? And the only way that would be yes is if I was absolutely convinced [Davis] couldn’t make it, and I’m not there,” she told me later that day as we talked about how she made that decision.

That evening I was talking to my editor at The Times when she suddenly got the news that action movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger had entered the race, announcing it during a taping of “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.”

It was selfish for Sen. Dianne Feinstein to stay in office. The other side to that stubbornness: ramrod determination and an unsinking resilience.

I hung up and immediately called Feinstein. “Schwarzenegger just announced on the ‘Tonight Show’ that he’s running for governor,” I told her. There were several seconds of stony silence.

“I have no comment,” she said. “I don’t want to say anything.”

By the next day, she had plenty to say, calling the race “a first-class carnival” and candidates Schwarzenegger and Democratic Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante opportunists. I watched from the sidelines as she gave TV interviews from the Aspen Institute campus.

She told me later that she had called high-ranking Democratic state officials and urged them not to run, including Bustamante and Controller Steve Westly, who had also entered the race.

Even as she lashed out at the race itself and the candidates, she seemed to be ever so slightly backing off her promise not to get into the race — telling one interviewer that she would “not at this time” reconsider.

Were there any circumstances under which she would enter, I asked her later?

By now she was just irritated by all the questions. “I mean, if there were, I probably wouldn’t talk to you, you know?” she answered.

Mostly, she seemed frustrated by the way the whole race had become a runaway train. Her pleas to Democrats to stay out of the race had been ignored and other Democrats kept pestering her to get in. She believed when voters saw how ludicrous or inexperienced the other candidates were, they wouldn’t recall Davis: “People will decide that after electing a governor nine months ago with 3.5 million votes, maybe he should be entitled to serve out the rest of his term.”

Of course, she was very wrong about that. But the one thing she got completely right — staying in the Senate.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.