Editorial: The research is clear. Money bail doesn’t make communities safer

The judge presiding over the ongoing lawsuit to end the use of bail schedules in Los Angeles County considered studies and testimony from experts in academia who have examined the effect of money bail requirements and programs that reduced or eliminated them.

There were two principal questions: Were suspects released without bail less likely to show up in court for mandatory hearings? And were they more likely to be arrested for new crimes?

The evidence pushed in a single direction: Eliminating money bail did not increase either failures to appear or rearrests. In fact, it showed that both court appearances and public safety improved.

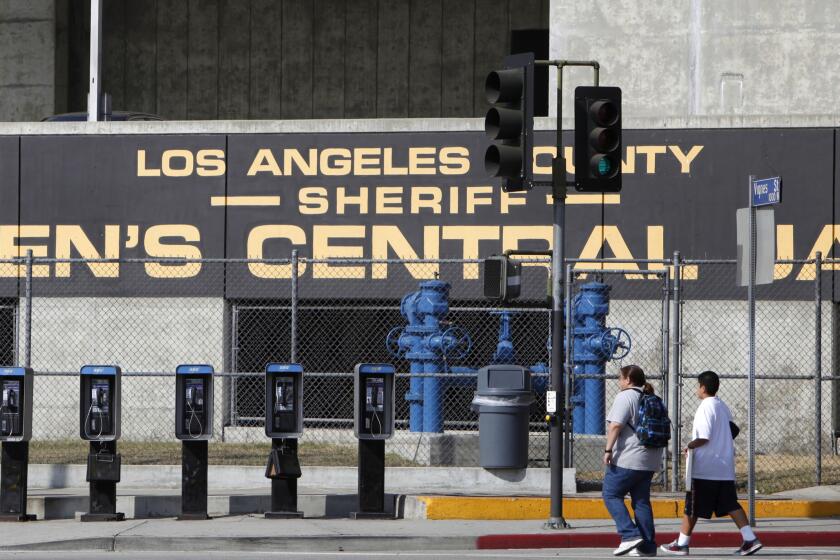

On Oct. 1 Los Angeles County transitions to a new way of administering pre-arraignment justice that doesn’t use cash bail for most crimes.

Studies of jurisdictions around the country, including New Jersey; Harris County, Texas; Kentucky; Miami-Dade County, Fla.; California’s Orange County; and counties in Colorado, Washington state and North Carolina, all show similar results, and some show that money bail and pretrial detention are correlated with significant harms for the defendants — while also making them more likely to be charged with new crimes.

Together, the studies create a body of evidence, widely accepted among social scientists and criminologists, that shows money bail does none of the good things that its proponents claim it does. Eliminating it causes none of the disasters they warn about.

We are jailing thousands of people because they do not have money to buy freedom. It is morally unconscionable.

Yet these studies and their remarkable conclusions — and obvious policy implications — never seem to make the evening news or the daily headlines. That leaves the public with a dangerously skewed view of the truth.

Instead, news reports, police and politicians routinely cite a survey from Yolo County, west of Sacramento, purporting to show increases in crime caused by the release of suspects under emergency zero-dollar bail requirements that were ordered to reduce the jail population to help halt the spread of COVID-19 in those facilities.

A lack of understanding around California’s bail system weakens public trust in the rule of law.

Yolo County Dist. Atty. Jeff Reisig said his figures show conclusively that zero-dollar bail leads to more crime.

But his survey was only a tabulation of numbers that didn’t compare similarly situated groups under circumstances that control for variables, like health and social conditions during and after the worst of the pandemic, or whether enforcement was increased during the period reviewed. The academics who study the effect of criminal justice policies widely criticize the Yolo report.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna, testifying in Urquidi vs. Los Angeles, the case challenging pre-arraignment bail, said his department likewise found high numbers of rearrests among defendants who were released on zero-dollar bail. But on cross-examination he acknowledged that the numbers were not part of any empirical study that compared the people released with and without money bail and controlled for variables. His department was “just counting.”

The money bail system betrays a host of fundamental American values, including the presumption of innocence, the right to counsel and equality in the eyes of the law.

L.A. County participated in a pilot project that eliminated money bail and pretrial incarceration for cohorts of criminal defendants beginning in 2020, and reported positive results: fewer failures to appear, fewer rearrests. That report falls short of the academic rigor of many of the other studies, but it’s important to note that the results were nevertheless far different from those reported in Yolo.

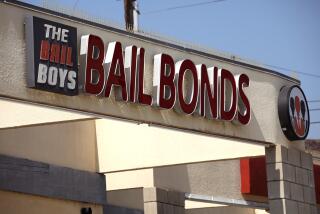

Like the academic studies, the L.A. County report didn’t make any headlines. News that tends to confirm our worst fears or deepest suspicions is widely repeated, especially by those with a stake in the outcomes, like the bail bond industry. Peer-reviewed academic studies, by contrast, go generally unseen by the public.

L.A. officials knew the bail schedules they used to lock people up before trial were unjust, but they didn’t act. Now a ruling will force them to do so.

Even the persuasive expert testimony in the Urquidi case, upon which Judge Lawrence Riff partly relied in issuing a preliminary injunction against reliance on money bail schedules to determine who may or may not go free between arrest and arraignment, has garnered little public notice. There is little public appetite for academic studies, but a seemingly insatiable hunger for news about crime.

When science is not understood, we end up believing in fairy tales.

The story that money bail increases public safety is one such fairy tale. It is as insupportable as the notion that Earth is flat, vaccines are a plot to control our minds, and the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. Some of these myths are serious threats to liberty and democracy. Preserving those gifts requires Americans to do a little homework, read past the headlines and study the conclusions of experts, or at least of the judges who have considered their evidence.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.