Opinion: The Supreme Court is making religion an all-purpose excuse for ignoring the law

Looking for a federal law to be declared unconstitutional? Religion may well be your best bet — and that’s true regardless of how “real” your religious beliefs are.

That’s part of the thinking behind one case the Supreme Court heard this session and will resolve soon. In 303 Creative vs. Elenis, the court is considering the constitutionality of a Colorado statute prohibiting most businesses from discriminating against LGBTQ+ customers. Lori Smith, a Christian webpage designer, had wanted to expand into the wedding website business — but only for opposite-sex couples, a plan that would have violated the Colorado law at issue. Her lawyers made the case on free speech grounds, but given Smith’s religious beliefs, “religious freedom” represents an undeniable backdrop to the suit.

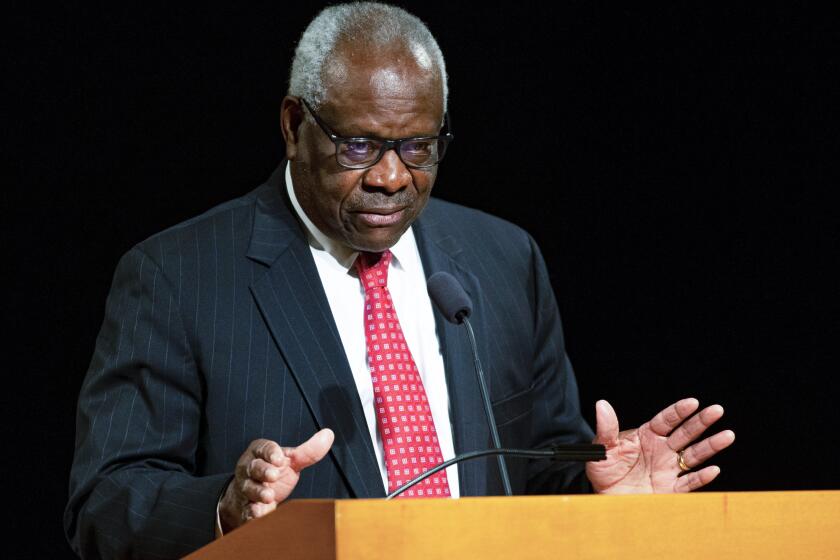

How hard could it be for Clarence Thomas, the longest-serving Supreme Court justice, to figure out how to follow financial disclosure law?

The 303 Creative case is no outlier. Religion-based claims have proliferated in recent years, and plaintiffs have often won because courts have almost invariably found their religious beliefs to be sincerely held. Meanwhile, the burden of proof for the government — that it is not unduly interfering in religious practice — has become much harder to prove.

A string of recent Supreme Court cases demonstrates how religion offers litigants a ready path to disobey laws without consequence. In the 2021-22 term alone, the Supreme Court decided several high-profile cases that affirmed religion’s supremacy.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s 2003 prediction that affirmative action college admissions would only last 25 more years may come true if the current court has its way. That would be tragic.

In Kennedy vs. Bremerton School District, the justices determined that a high school football coach could not be placed on leave for violating a rule against public prayer. In Carson vs. Makin, it held that Maine was constitutionally required to subsidize religious schools. And in Ramirez vs. Collier, it postponed the execution of an inmate after he asked, at the 11th hour, that his pastor lay hands on him — despite having previously explicitly disclaimed the same form of relief.

Then, in a narrow 5-4 decision last September, the court left in place a New York state court decision requiring Yeshiva University to recognize an LGBTQ+ student group over the school’s purported religious objections. Ruling on technical grounds, the majority directed the university to first seek relief in state court. But four dissenting justices would have granted review to vindicate the university’s 1st Amendment rights — and those justices say that the university would “surely” win if the case comes back up, after state proceedings conclude.

How did these results come to be?

In the conventional understanding, religious exercise was cast off as an almost disfavored right. Courts were, historically, generally willing to let the government prevail whenever public policy and religion came into conflict. Now though, when the court says that government action affecting religious exercise must satisfy “strict scrutiny” — a notoriously difficult burden — it actually means it.

A bipartisan bill would require a code of conduct for justices and create a process for complaints against justices to be filed and investigated.

But that’s not the full story. Courts aren’t just making it harder for the government in these cases; they’re also making things easier for plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs must in theory show that their religious beliefs are sincerely held before strict scrutiny can kick in. This requirement dates to a 1944 decision, United States vs. Ballard, which for many years served as an effective gatekeeper against cries of “religion” casually trumping the law.

But in practice, this requirement has been hollowed out since at least the early 1990s.

Today, many claims for “free exercise of religion” arise under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act. I conducted a systematic review of roughly 350 such cases decided by the Supreme Court and the federal appellate courts over the last 30 years. Since the passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993, the Supreme Court has always found plaintiffs sincere. Lower federal appellate courts found plaintiffs sincere in 270 out of 291 (93%) cases from 1994 to June 2022.

This marks a striking difference from other areas of law, in which plaintiffs are frequently unable to meet their burden. For instance, employment discrimination plaintiffs meet their burden just 27% of the time and antitrust plaintiffs only 16% of the time. In other words, the onus on the plaintiff poses a meaningful barrier to obtaining relief — except in religious free exercise cases.

Litigants have taken note. The rate of claims under those two religion-related laws has tripled since the 1990s. It has become easy for a plaintiff to win by leveraging beliefs, even if their “religious belief” is just a ruse to get into federal court.

The relaxing of the sincerity requirement has real-world consequences across many fields.

For instance, courts allowed plaintiffs to skirt COVID-19 vaccine mandates based on religious objections to the use of embryonic tissue in research development and testing. Never mind that those same methods were used to develop everyday medications such as Benadryl, Claritin and Tylenol. And the Supreme Court set aside COVID restrictions on gathering sizes to accommodate religious events.

Education hasn’t escaped the religious beatdown, either. States now must provide funding to both secular and religious private schools, or only to public schools. And many teachers at church-run schools are not protected by federal employment discrimination laws.

The decision in Allen vs. Milligan is most significant for what the court didn’t do: It did not further weaken the law of voting rights as many expected.

Further, these teachers — and any other nongovernmental employees — may not be able to receive contraceptive care through their employer-provided health insurance after religious objectors attacked the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. And, emboldened by recent judicial decisions, Catholic hospital systems and certain insurers have begun denying LGBTQ+ people fertility treatments.

It’s clear that the sincerity requirement needs an overhaul. And there are several possible routes to fix this now-empty requirement.

One way is for Congress to amend the law to make the plaintiff’s burden more demanding, make the government’s burden easier, or exempt certain regulations (such as those governing public health) from being attacked through the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Courts have a role to play here, too: They could tighten the screws by conducting a more rigorous analysis of sincerity.

Fixing the abuse of this criterion won’t be simple, especially with a deeply divided Congress and a conservative stronghold on the Supreme Court. But change is needed, or litigants will continue to use religion as a pretense to break the law.

Xiao Wang is a clinical assistant professor of law and the director of the Appellate Advocacy Center at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.