Editorial: China is not a credible peacemaker in Ukraine war

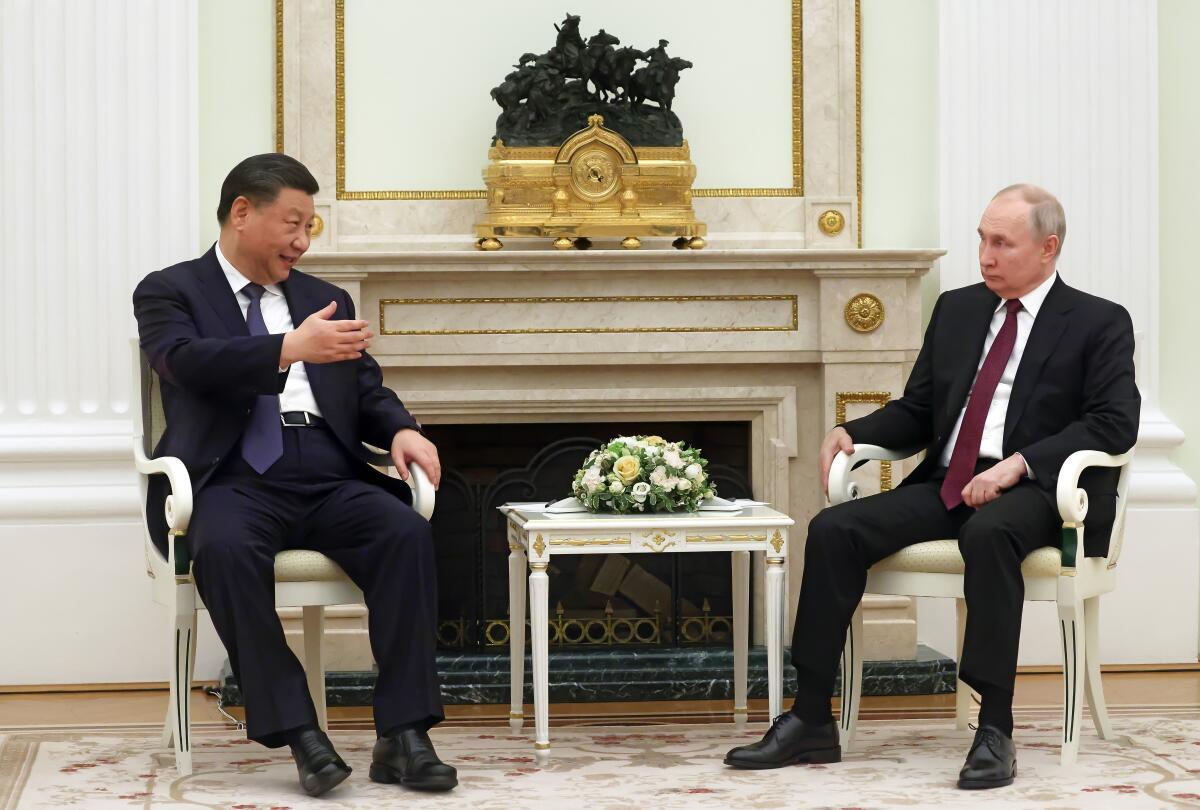

Whatever else it produced, this week’s visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to Moscow did not advance the cause of a just peace in Ukraine. If anything, Xi’s cordial courtship of Vladimir Putin provided the Russian president with a publicity coup days after the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Putin and a key minister alleging they committed war crimes.

Under Xi, the People’s Republic of China has asserted itself on the international stage. For example, leveraging its economic influence, China recently brokered a resumption of diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, a potentially positive development for peace and stability in the Middle East. But given its ever-closer relationship with Russia, China cannot credibly play the role of peacemaker in Ukraine.

Its 12-point peace plan — which Putin praised on Tuesday — says that the “sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries must be effectively upheld.” But its call for a “comprehensive cease-fire” and the resumption of peace talks would lock in Russian gains. On Monday, Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken warned: “Calling for a cease-fire that does not include the removal of Russian forces from Ukrainian territory would effectively be supporting the ratification of Russian conquest.”

Losing the war in Ukraine is the best hope for Russia to get back on the path to economic and social stability.

In a joint statement released on Tuesday, the two parties exchanged compliments, with Russia praising China’s “objective and impartial position” on the Ukraine issue and China saluting Russia’s willingness to resume peace talks. Obscured in the mutual flattery was the larger context of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in violation of international law.

This brutal conflict may indeed end in negotiations, but as the victim of aggression Ukraine must decide when it makes sense to come to the table. (President Biden has said that the goal of U.S. military assistance is to help Ukraine “so it can fight on the battlefield and be in the strongest possible position at the negotiating table.”)

China’s coziness with Russia, celebrated in the pomp of Xi’s visit to Moscow, undermines any suggestion that Beijing is “objective and impartial” when it comes to the Ukraine conflict. The lingering question is whether it will provide military aid to Moscow. Last month Blinken said the United States had information that China was “considering providing lethal support.” He added that “we’ve made very clear to them that that would cause a serious problem for us and in our relationship.” Biden said last month that the U.S. “would respond” if China provided Russia with weapons.

It’s bad enough that China, while not endorsing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has refused to join the U.S. and other nations in forthrightly condemning that act of aggression. But actually helping Russia to wage war on Ukraine would be even more dangerous — and harmful to China’s interests.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.