Op-Ed: No matter what happens in the midterms, pundits will trot out familiar narratives

- Share via

Regardless of what happens Tuesday, we’re going to hear plenty of attempts to explain it from TV pundits and party leaders. A lot of those narratives will sound pretty familiar — really, we can write many of them now. But they differ across parties, and that has some important effects on the way voters and leaders behave.

Narratives are an important part of our lives, and not just in politics. They’re the stories we construct to make sense of a complicated world. As Joan Didion wrote, “We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five.” An election involves tens of millions of voters making a series of decisions based on any of hundreds of different motivations. To say exactly why Joe Biden beat Donald Trump or Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter is impossible, but the stories we construct can be helpful for simplifying these events and telling us what to do in their wake.

What are the narratives going to be Tuesday night? It’s fairly easy to know these ahead of time. If Republicans take both chambers of Congress, pundits will broadly blame Democrats for being too “woke” and will hail Trump as a kingmaker. If Republicans take the House but not the Senate, it’ll be interpreted as a call by the American people for politicians to work together across party lines. If Democrats hold both chambers, pundits will say it is because of Trump’s corrosive influence. In all circumstances, Democrats will be advised to moderate.

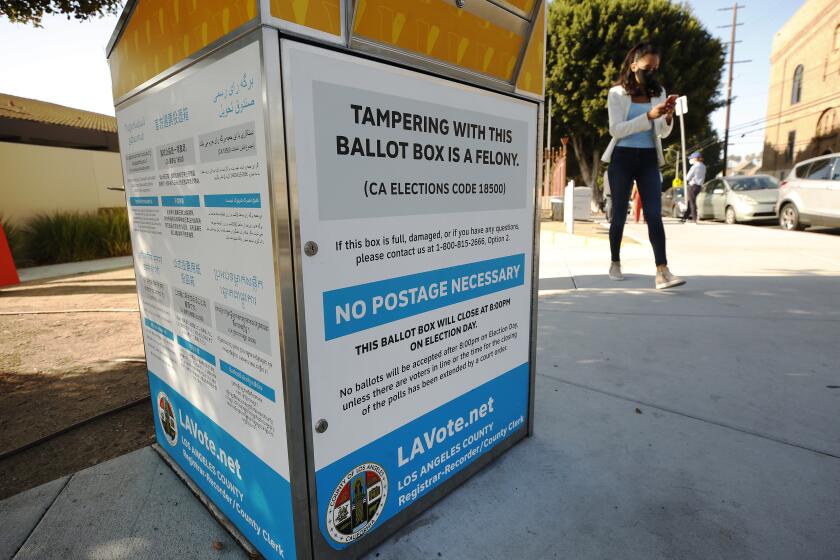

We’ve rounded up election guides and endorsement lists from newspapers, other media outlets, political parties and others across the state. Consider this your guide to voting guides.

How do we know these will be the narratives? Because they pretty much always are. Network news pundits often rely on some tried-and-true storylines to fill airtime on election night. They’re being asked to come up with something to say before they have data, and these analyses can sound reasonable. The pundits might even earnestly believe them. Once in a rare while, a political observer learns something new from an election and it changes that person’s views, but that’s definitely the exception.

Party leaders develop fixed views about elections as well — though they don’t always agree. Indeed, sometimes one faction in a party will develop a narrative to blame the other faction for a loss. We saw this after the Virginia gubernatorial election last fall, when centrist Democrats blamed the progressive left for making the party unelectable and the progressives blamed the centrists for not knowing how to run campaigns.

We saw it after Mitt Romney’s loss to Barack Obama in 2012, when the more establishment wing of the Republican Party produced its famous postmortem saying that the party was being perceived as too hostile to women, minorities and immigrants thanks to its nativist wing. These narratives are an attempt to pull the party in one direction or another, but also for one faction to say that a recent election loss wasn’t their fault.

But importantly, election narratives vary considerably across party lines. Republicans interpret election losses very differently from Democrats, in looking back at half a century of evidence.

The default position of the news media is still to focus on politics as sport. But if the enemies of democracy win in the midterm elections, there will be no ‘wait till next year.’

For Democrats, the persistent narrative of the last 50 years is that they lose when they’re too liberal and they win when they moderate their positions. They look at George McGovern’s loss in 1972, Walter Mondale’s in 1984, Al Gore’s in 2000 and Hillary Clinton’s in 2016 and conclude that they lost those contests for being perceived as too far outside the mainstream. The lesson they point to is about taking power with moderate candidates like Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. Joe Biden’s victory in 2020 ratified that viewpoint for them.

For Republicans, the persistent narrative of the last 50 years is that they win when they stand up for what they believe. They were told Ronald Reagan was too extreme to win; he won. They were told they needed to moderate with candidates like John McCain and Mitt Romney to win; they lost. They were told Donald Trump was unelectable, which he was until the moment he got elected.

Neither party is exactly wrong — there most likely is some sort of “electability” effect, where more moderate candidates do a bit better — but that effect is likely smaller than Democrats think and larger than Republicans think.

However, these different storylines do lead to very different party behavior. Democrats are constantly trying to downplay their more liberal members’ desires. Biden has gone out of his way to distance himself from the idea of defunding the police, calling for just the opposite. Indeed, many Democrats who considered Biden only their fourth or fifth choice in 2020 supported his nomination because they believed only he was electable — that he was moderate enough to win while other Democrats couldn’t.

Contrast this with the behavior of Republicans, who largely ignore abhorrent statements from the likes of Lauren Boebert and Marjorie Taylor Greene and downplay attempts to undermine democratic elections by Trump supporters. Indeed, consider prominent Republicans who, following an attempted attack on the speaker of the House, made light of Paul Pelosi’s injuries and spread conspiracy theories about him. Try to imagine if one of Biden’s children had mocked Steve Scalise after his 2017 shooting, as Donald Trump Jr. did recently with the Pelosis. If that had happened, Democrats would still be apologizing for it to this day.

Democrats run as though their more extreme members will cost them elections, and Republicans run as though their more extreme members will help them win. This isn’t to say that one party has unlocked the truth about elections and the other is delusional. Each pursues a strategy guided by long established frames of reference, and each has held the White House and Congress for roughly similar numbers of years in the last few decades.

In the hours and days following Tuesday’s election, listen to the analysts and think about which of them is telling you something new.

Seth Masket is a professor of political science and director of the Center on American Politics at the University of Denver.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.