Op-Ed: I’m an Asian American Harvard grad. Affirmative action helped me

The Supreme Court will begin hearing arguments in two cases at the end of the month and could decide the fate of affirmative action in higher education. In 2018, I testified before a federal judge in one of those cases, Students for Fair Admission vs. Harvard, attesting to the importance of affirmative action in my life and why it is valuable to the Asian American community.

I am the daughter of working-class Chinese immigrants who speak very little English. I was born at Chinese Hospital and grew up in Lower Nob Hill in San Francisco. My parents worked at restaurants for low wages, and our family of six barely scraped by. We lived in a cramped one-bedroom apartment among urban professionals and underserved communities.

Before I was even a teenager, I advocated and translated for my family. In my household, my siblings and I are the first generation to graduate from college. In my personal statement for my college application to Harvard, I wrote about how these experiences shaped my passion to do work that would help others with similar struggles.

When public med schools drop affirmative action, they admit fewer students from underrepresented racial groups.

I began at Harvard in 2015. During my first year, I was miserable and homesick, but I eventually found an academic home in my ethnic studies classes and a broader sense of belonging through campus organizing related to racial justice. At a student activism meeting in 2017, a friend shared how to file requests under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act to see my admissions file. Curiosity and a lingering impostor syndrome led me to test out the process.

The registrar’s office gave me 45 minutes to view my file. My admissions readers saw value and authenticity in my perspective: “Categorized as low-income and with Taiwanese-speaking parents, she relates to the plight of the outsiders in Ralph Ellison and William Faulkner.” Though my test scores were far from perfect, they believed that I had the potential to make a “contribution to college life” that would be “truly unusual.”

I benefited from an admissions process that took race and the effects of racism into consideration. My story can’t be conveyed in a race-blind way and during the Harvard trial my admissions file was used as an exhibit to illustrate this. The benefits of affirmative action carried over into my classroom experience as well, where I had the chance to learn from classmates who came from very different backgrounds than my own.

After graduation, I packed my bags and moved back home to that one-bedroom apartment, determined to get to work. By day I worked in multiracial coalitions for policies that could help immigrant working families, such as investment in workforce training for communities of color. At night I continued to navigate complicated systems and programs as a client, applying for affordable housing through Asian American nonprofits and taking my parents to Chinatown outreach sites for COVID-19 vaccines. Doing this work — for myself and for others — gives me hope that someday everyone can share the belief that a more fair and inclusive society is a better one.

The injustices I grew up witnessing and experiencing still permeate our lives. The Supreme Court shouldn’t end affirmative action. The U.S. needs more such programs and policies that address the inequities that people face in this country.

The high court is breaking with tradition by reaching out to decide cases to further its conservative vision even when there is no disagreement among the lower courts.

Some people point to Asian Americans, the “model minority,” being well represented at elite universities as a reason race-conscious policies aren’t necessary in higher education. The plaintiffs in one of the Supreme Court cases accuse Harvard of discriminating against Asian American applicants even though at the lower courts, no evidence of this was found. I am just one of many Asian American students and alumni who believe the university’s race-conscious policies helped our admission and made our education better.

Asian Americans need and benefit from affirmative action. Almost 70% of Asian American voters support affirmative action. And in states such as California, where the program has been banned since 1996, universities have struggled to increase diversity without it.

Affirmative action is successful because it opens doors for people who would otherwise be excluded — and because it recognizes that everyone benefits from having diverse perspectives at the table. The program is an acknowledgment that our education system isn’t fair, and laws that help remedy its inequities are necessary. If the Supreme Court ends affirmative action, as many predict, I’ll be among its last beneficiaries. And I’ll continue working to help those like me, who deserve access to the opportunities a great education can provide, and who will pay that benefit forward when they get it.

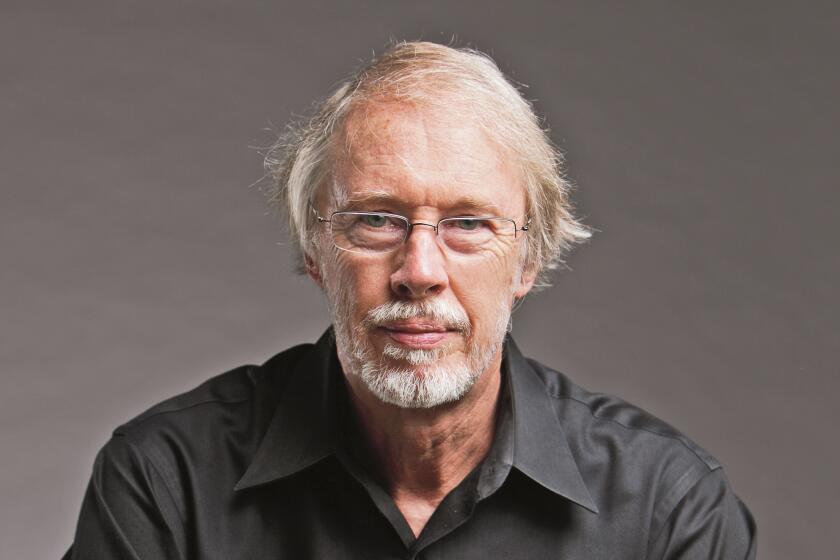

Sally Chen is the education equity program manager at Chinese for Affirmative Action, where she helps create opportunities and access for low-income Chinese immigrants at all levels of education.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.