Column: The Supreme Court should find the Roe leaker. But that won’t fix what’s broken

- Share via

The Supreme Court’s investigation into the leak of the draft opinion overruling Roe vs. Wade is reaching a boiling point, with law clerks reportedly being required to turn over their cellphone records and sign affidavits — under penalty of perjury — disavowing any role in the leak.

According to one CNN commentator, the strong-arm tactics have the nearly 40 clerks “freaking out,” and they contemplate lawyering up. The court’s hardball investigative moves have drawn harsh criticism: Jennifer Rubin in the Washington Post called the actions an “unseemly dragnet,” and lawyer and legal commentator Leah Litman (no relation) termed them “insanity.”

I’m a mild dissenter from the outrage at the investigation’s starchiness. The leak was a grievous transgression, and the seriousness of the response should neither surprise court insiders nor leave them indignant.

What the leaker did may not have broken a specific law (a bill was just introduced in Congress to remedy that), but when it comes to court culture, it was the equivalent of a capital offense.

Chief Justice Roberts calls the leaked draft a “betrayal” and says it will be investigated.

More importantly, the leaked draft, and other bits and pieces that have continued to surface regarding the progress of the Roe decision, confirms that the Supreme Court itself is broken. But here, the leak is more a symptom than a cause.

It’s hard to describe to outsiders just how big a sin the leaked draft is in terms of Supreme Court culture. I was a clerk for Justice Anthony M. Kennedy in the late 1980s, during a term with a very high-profile abortion case that portended the overruling of Roe. That the draft opinion on that case — or any case — would wind up published was inconceivable then. The appearance of Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s full Roe draft in May was as unprecedented as it was shocking.

Chief Justice John G. Robert Jr.’s investigation, and his fury — he called the leak “an affront to the court and the community of public servants who work here”— is completely understandable.

The Supreme Court is a deliberative body, at least in design, and its drafts are the actual means of persuasion and coalition-building. They are meant to be written candidly and confidentially, then probed, discussed and adjusted according to colleagues’ comments. There is no bully pulpit, as with the president, no heated exchanges on the floor of the Senate. The back-and-forth of arguments made in writing is the decision-making process.

The conservatives have embarked on a crusade of judicial activism against a raft of precedents, and not just on abortion.

That process has been unalterably corrupted by the leak. Any justice writing a draft opinion must now consider that it could wind up in the public sphere, awash in political crosscurrents that should play no role in Supreme Court deliberations.

Justice Clarence Thomas has been mocked for saying, with characteristic dyspepsia, that the leak “changes the institution fundamentally…. You begin to look over your shoulder. It’s like kind of an infidelity, that you can explain it, but you can’t undo it.” But he’s right about the leak’s impact.

So the court simply could not let the leak pass. A concerted effort to find the leaker (or leakers) is necessary, if only for the sake of deterrence.

Which brings us back to the investigation itself.

As far as we know, only the clerks are being asked, as a work requirement, to turn over their phones and sign affidavits. They are the logical focus of Roberts’ inquiry. They mirror the passions and positions of the justices they work for; indeed, they increasingly have been chosen because they are soldiers for shared political and legal causes. And the court, as their ultimate boss, has considerable leverage to get them to cooperate with the ask — if they don’t comply, they could be dismissed, a severe blow to their future careers.

Others at the court — administrative employees, for example — may have had access to the draft opinion, but they are much less likely to be privy to the added tidbits that have dripped out — that no other Roe drafts had circulated and no justice changed his or her vote. As for the justices themselves — it’s not only unthinkable that they would be the source of the leak, targeting them would be tanatamount to dropping a bomb in the middle of the conference room. In any case, the chief justice has little leverage to force his colleagues — with their lifetime tenure — to cooperate with this investigation.

The leak of a U.S. Supreme Court draft opinion about Roe vs. Wade underscores how the court still operates in enormous secrecy. What if it didn’t?

In the long run, expending outrage over the investigation targets and its process obscures what the leak clarifies: The Supreme Court has become a very public train wreck.

Those who caused the crash are, for the most part, political actors, outside the court itself — Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell foremost among them. And the crash they caused was the installation of a supermajority of justices eager to take a sledgehammer to many of the foundations of American constitutional law.

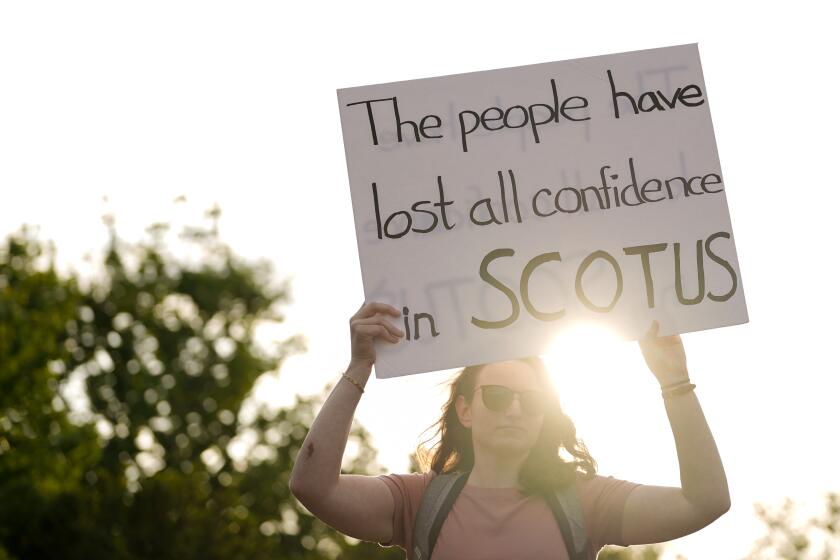

The Roe leak has further undermined what was already crumbling. In many important cases and respects, the court has ceased to be the trustable deliberative body of constitutional design. It is in the iron grip of a five-justice bloc that is out of step with the legal community and the American public, one that has the power to ignore reason and argument from the rest of the court.

An ill-gotten supermajority degrades the Supreme Court and leaves it, in the broad perception of the country, hopelessly politicized. The leak is important — it matters. But however the investigation turns out, it can’t repair this bigger problem.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.