Column: What the death of my friend Mando Montaño taught me about grief

- Share via

During one of the last weekends of Mando Montaño’s life, he and I went to a Mexico City club known for its dance-off circles. Bursting into one circle, Mando moved to the beats like he was the Big Bang itself.

Unruly dark curls flying, limbs alight with rainbow lasers, he was cosmic in groove and gyration. Gorgeous like Clark Kent, if the superhero was proudly gay and Mexican American. Mando couldn’t fly, (“obvio,” he’d say), but zoom into his heart and you’ll see a gift that’s like a superpower: bridging divides.

He was the journalist we need today in our fractured country.

On June 30, 2012, he was found dead at 22 in an elevator shaft near the building where we both lived in Mexico City as we started our careers. The case remains unsolved. Questions still swirl dizzyingly around it. Why was he in that building? How did he end up inside the elevator shaft? Was it an accident? A hate crime? A random murder? Was he targeted for his recent reporting on a police shooting?

A black hole’s event horizon is a point of no return, the boundary where escape requires violating the laws of physics by surpassing the speed of light. For years, his death’s unfathomability had a gravity so immense it felt annihilating to approach. Only recently did I find courage to venture toward it.

Opinion Columnist

Jean Guerrero

Jean Guerrero is the author, most recently, of “Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump and the White Nationalist Agenda.”

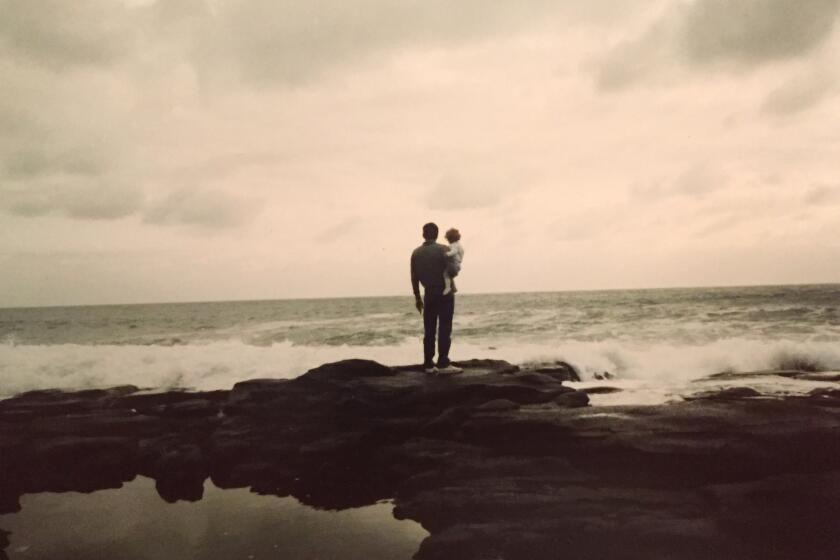

Months before he died, he published an essay in Salon about yearly road trips along the southern border with his father, a Mexican anthropologist. He explored his biracial identity; his mother is white. One early trip, a white man in West Texas turned his brown father away from an empty hotel. Back on the road, Mando — still a child — was frustrated. “I hate white people,” he declared. His bespectacled dad pulled over and stopped the car. He told his son never to repeat those words. He asked: “How would your mother feel if she heard you say that?”

Mando was interested in challenging our instinct to dehumanize one another, and was entering the business just as a race-baiting reality TV star was using Twitter to spread the birther conspiracy theory about then-President Obama.

He was in Mexico City for an internship with the Associated Press — drawn there, like I was, by curiosity about his dad and love for journalism, his mom’s vocation. I was two years older and worked for the Wall Street Journal bureau there. Mando and I had met as Seattle Times interns three years before. We became friends, staying in touch through Facebook. He moved into my building because I suggested it. I thought the neighborhood, La Condesa, was safe.

We knew Mexico was experiencing record-high homicides. Today, it’s the most dangerous country to be a journalist. But correspondents are less vulnerable than local reporters. We loved Mexico and wanted to tell its many stories, which are not all cartels and violence. Mando wrote about baby elephants and Justin Bieber fans in the capital. One night, I heard him on the phone with his mom, who worried about him; he reassured her he was safe because he was with me.

On Friday, June 29, he came over to ask if I wanted to go out that night. I told him I was tired of going out so much and was going to stay in and binge-read in bed. We gossiped about boys and agreed to meet on Sunday at the Institutional Revolutionary Party to cover Mexico’s presidential election results. Then he left.

The next morning, his mother told me on the phone that he was dead. My brain repeatedly tackled that word, “dead,” in a futile effort to absorb it despite its impenetrable weight.

Denigrating multilingualism is rooted in the desire to restrict who can belong here. Saying our true names is one way to fight that idea.

Research in psychiatry shows trauma is debilitating as long as our memory of it remains frozen in time. We need ever-changing stories to heal. Trauma dims our capacity for joy and comfort; reinterpretation breathes life back into our bodies.

For years, the story I told of Mando’s death was that he’d be alive if he had never met me. I had advised him to live on the block where he died. A friend I had introduced him to had put him in a cab home by himself on his last night when he’d been drinking. Mando had never let me get in a cab at night by myself.

His joyful presence had helped me emerge from a period of flashbacks connected to a near-drowning incident I’d had in 2011. After he was gone, those symptoms returned. I felt dead to all but fear, which hurt my relationships and my ability to live in the moment. I tried to escape my guilt-warped grief and dread by burying them.

But recently, I found myself digging them back up as I prepared to give the annual Armando Alters Montaño Memorial Lecture at Grinnell College, where Mando studied Spanish and Latin American studies. I was surprised to discover that doing so did not destroy me. Walking around campus with Mando’s parents, Diane and Mario, they told stories that made him flicker back to life.

As I spoke with them and others who loved Mando, the ghost I carried changed. Mando came back to me as he was in life: effervescent, encouraging, hilarious. I listened to Hot Chocolate’s “You Sexy Thing,” which his friend Zach Ben-Amots remembers him dancing to spectacularly, and I grooved wildly in his honor. I cried and laughed; my grief changed color as it mingled with fuller gratitude for my friend.

“It’s actually very meaningful to be surrounded by the dead,” Aaron Edwards, a Black gay journalist and one of Mando’s best friends, told me. He still reads the texts and email they exchanged. “There was no one who came close to the level of energy and positivity and gusto that he had,” he said. “We were all …” he paused to find the words. “We were all just like branches on his tree.”

Grieving Mando taught him to be wary of America’s response to COVID. “Our country has been charging forward to revitalize economies before we revitalize the hearts of people who’ve lost people they love,” he said. “I just wish for a world in which you could lose someone and actually hold space for what that means.”

Holding that space helped Mando’s friends explore their own life goals. Stephen Salazar Ceasar, for one, left journalism to work on alternatives to incarceration at a nonprofit after reflecting on Mando’s empathy, which he said “centered what I wanted to do with my life.”

During a 2020 stint in Mexico City, Marissa J. Lang, a Washington Post reporter, put photos of Mando around her place and left flowers for him around the city. “I’d kind of talk to him,” she told me. “I felt like I could tap into his energy a little bit. His playfulness, his humor.” She had feared facing her grief. But, she realized, “opening that box up again can be a really rewarding and beautiful experience.”

Recently, I pulled up my old photos of Mando in Mexico City. I’d never looked at them without a sense of ghastly wreckage. Now, the photos brought me joy, too. I took one of him posing on my Yamaha FZ16 motorcycle. He’d suggested a sexy photoshoot after he learned I didn’t have such pictures. He didn’t want to take it for a spin. He didn’t chase danger like I did. He just thought it would be a fun, goofy thing to do together. In my photos, his eyes are infectiously kind.

Mando taught me many lessons: about dancing fully, about being a good friend, about community as a practice and a priority. He gave me advice I took, such as to join the National Assn. of Hispanic Journalists. When I told him I was considering quitting my job to write a book, he told me to go for it. The spring after he was gone, I did. I dedicated my second book to him.

His promise was so obvious that the New York Times Student Journalism Institute named a scholarship after him while the institute existed. His old mentors talk about him to new students. “I still invoke him,” Rick Berke, a former New York Times editor who mentored him at the institute, told me. Two of his professors, Ralph Savarese and Dean Bakopoulos, dedicated books to him.

In her devastating poetry book, “Breath, Suspended,” his mother writes that Mando dreamed of getting married in the Newseum. The Newseum, now closed, was “where typewriters, Teletypes / Linotypes and laptops are all the same / to him — a way to tell stories.” For him, stories were a path to human connection.

It wasn’t until I revisited what Mando meant to me and listened to what he meant to others that I’ve come to understand the experience of losing him.

Grief can’t be fast-tracked. As a country, we can’t recover from our collective traumas, including the pandemic, until we process what we’ve lost. Mando’s loss helped me see that a refusal to examine death keeps us all disconnected from one another — and that sharing stories is an indispensable part of the path back.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.