Op-Ed: Miscarriage might be common — but the pain is unique to each of us

Over lunch on a Wednesday while working remotely, my husband and I debate the type of school our child, Ayesha, should attend. Later, we decide who will help with their homework and teach them science.

But the thing is — there is no Ayesha.

Ayesha has been dead, from a miscarriage, for over a year.

We all cope in different ways, and I have turned to a fictional universe where our child is still alive.

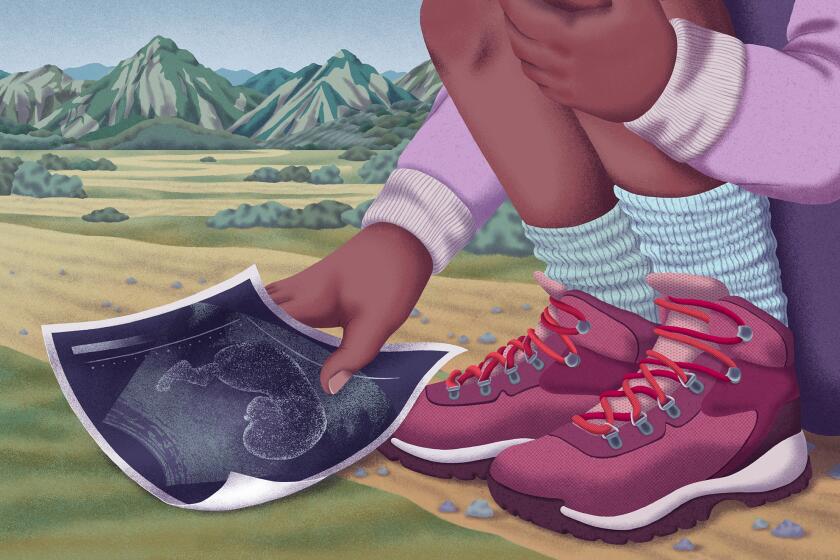

How hiking L.A. trails helped Kiana Butler find love and cope with loss after miscarriage.

One fall day, I went to the doctor for my ninth-week checkup. Then in my late 30s, I had gotten pregnant from our first intrauterine insemination. According to the book “What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” at nine weeks, our baby was as big as a green olive.

It was pre-COVID vaccine, when I had to go to the doctor alone, without my husband.

The doctor turned to me and said, “I have bad news.”

She moved the ultrasound monitor closer. I never liked looking at it but glanced for one second before turning my attention to the emergency sprinkler overhead.

“Your baby stopped developing.”

The tears came down, turning my fabric mask into a dirty rag.

“Is it something I did?”

“No,” she assured me.

My miscarriage started that Saturday, and I began to bleed my baby out naturally.

Sitting on the toilet, I took pictures of the blood clots of my baby so I wouldn’t forget. On my phone, next to pictures of what I ate for dinner, are photos of viscous red nestled on a super-size maxi pad. I was mesmerized by the gelatinous tulip bulbs coming out of my body. It was a placenta gone wrong, the darkest and brightest red I had ever seen. I felt attached to my child, as if the shot of dopamine they say attaches you to your baby in childbirth was happening to me now.

I didn’t cry. All my energy went toward getting through the cramps and not staining our white bedsheets. The tears would come, and still come later, triggered by strangers asking if I have children.

Just three weeks before, I’d taken the sonogram image to the Bay Area to show my proud parents. This would be their first grandchild. During that trip, I kept telling Mamuni (mother in Bangla), “I guess I’m one of the lucky women who don’t have morning sickness,” feeling smug.

After my miscarriage and two more unsuccessful IUIs, we took a mental break until we were ready to start in vitro fertilization. After two cycles of IVF, we received the news that our frozen embryo transfer didn’t work. It turns out I have low egg count. As this becomes our reality, now in our fourth year on this journey, we discuss our options and grapple with the possibility we may never have a baby at all.

My husband and I spend all our days in the same rooms together, and in our free time I like to talk about our child as if we have one. One Saturday morning, I ask him, “What if our child called us from summer camp, homesick and crying, and wanted to come home? Would you pick them up?”

I seriously think about this predicament as if our imaginary child just placed an imaginary phone call; he humors me and plays along. In these moments, I get into my car and drive toward a fictional town where I have to make decisions about a kid that’s not even alive. I enter into a part of my brain and start to drive. Perhaps it’s healing. A way to escape into my imagination and alter my reality.

We cannot let abortion be stigmatized by a minority that holds extreme views on what is a crucial human right.

Post-vaccine, my husband is allowed to come to my appointments. He swears he’ll never let me go alone again, even for a blood draw.

“Every time you go alone, it’s bad news.”

It’s become his own superstition.

I’ve learned, you don’t get over a miscarriage.

Even if society tells you it’s normal; it’s a part of life. It happens to everyone.

You live on, not move on.

And so, every morning, I imagine getting into my car in the San Fernando Valley and taking a right turn onto the highway northbound. I merge onto the I-5. I think about where my kid will go to school, if they will go to school. What kind of person will they be. Who might they marry. I picture that familiar road and keep driving and driving and driving. It’s a straight shot to the Bay Area, to my parents. Past the Sierra Pelona Mountains and the cow pastures. Past the garlic fields and dollar baby avocado fruit stands. I have done this drive a thousand times.

And tomorrow, as I sit in my loss, I will do it again.

Mahin Ibrahim is a writer based in Los Angeles whose work has appeared in the anthology “New Moons: Contemporary Writing by North American Muslims.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.