Op-Ed: You may not know his name, but for me Eric Priestley was a poet laureate of L.A.

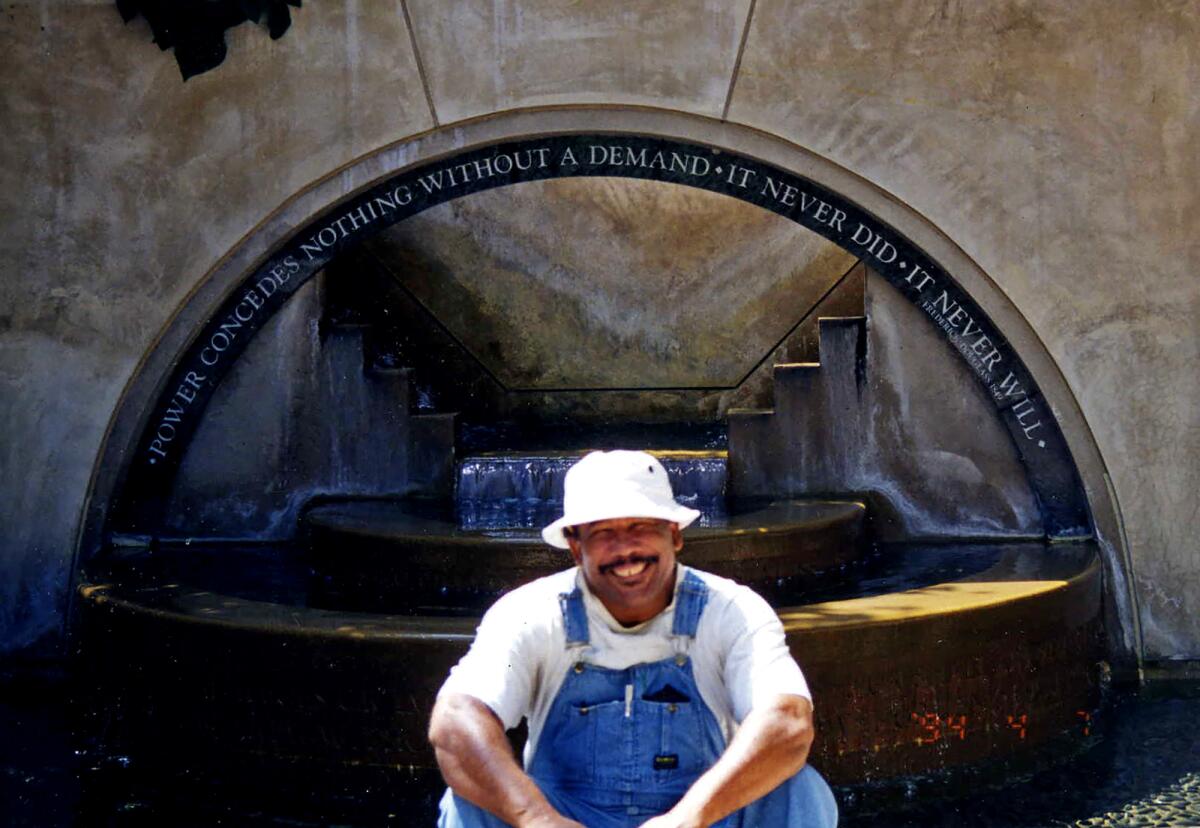

In the flurry of famous-people deaths that always seems to happen at the end of the year, I want to note that Los Angeles poet, novelist and screenwriter Eric Priestley died too, on New Year’s Eve, at the age of 78.

Eric was not exactly famous. He was locally known by a certain generation. An original member of the Watts Writers Workshop, he helped forge the city’s Black Arts Movement in that landmark literary circle started by screenwriter Budd Schulberg in 1965.

Eric’s was an outsized personality. He lived famously, which is to say that he believed in his talents and vision and saw them as eminently worthy of recognition.

His kind of fame didn’t mean mainstream status or wealth (he could have used a little more of the latter) but being heard, understood. The need to be understood drives all writers, and for Eric, who found his voice in the crucible of civil unrest stoked by longstanding racial inequality, the need wasn’t just personal. It was about justice.

Critical as the legal win is, it is also an admission that the fatal shooting of a Black man by white men determined to see him as a threat should never have happened at all.

I didn’t become aware of Eric Priestley until the 1990s. His poetry collection “Abracadabra” landed on my desk when I was a staff writer at LA Weekly. I was instantly riveted by these lines, from an early poem, “Lament on 103rd Street”:

homeless lay I high in the weeds

a seed in scorched soil

the bud in flames

amongst the other children

beneath the trees of night

“Abracadabra” was streetwise, cool and musical but also rapturous and specific. Here was a Black poet from hardscrabble Watts who didn’t simply decry L.A. as an urban wasteland or a long boulevard of broken dreams but saw in it something beautiful, unfinished, possible. I reviewed “Abracadabra,” declaring the writer a poet laureate of Los Angeles.

“Where has Eric Priestley been all our lives?” I wrote, and though I didn’t know it then, I was publicly putting him in the position that he took subconsciously: An artist who had more than earned the right to be known. It was just a matter of the world catching up.

We became fast friends, two L.A. natives with roots in Louisiana, and I’ve written about him more than once in these pages. Eric was a character, to put it mildly. His life had one compelling chapter after another.

Eric Priestley is out of his place. It’s odd to think of him being out.

In 1965, for example, he was 21 and living in a pool hall on Central Avenue when the Watts riots took hold. His description of that infamous August day — emerging from the pool hall to the sounds of breaking glass and a gathering crowd that increasingly sounded like a swarm of angry bees — was unforgettable. Woo woo woooo was how he explained the noise to me, capturing with startling accuracy a collective surge of grief and menace.

That memory for Eric inspired fear and anger but wonder too. He stood for social justice, but he was also a keen observer and appreciator of the surreal. “E., you are not going to believe this!” was how he typically opened a conversation (he added a word to the end of that sentence The Times won’t print).

A habitual public transit rider, Eric reported on goings-on all over L.A., from the mundane (a strange incident at a grocery store on Crenshaw) to the electric (in a serious instance of déjà vu, he found himself squarely, but accidentally, in the middle of the 2020 George Floyd protests near Hollywood).

He narrated it all with a kind of breathlessness that could be overdramatic, but that was his point: Everything had inherent drama, everything mattered.

You have to believe in the possibility of a just America in order to feel betrayed by the unjust one.

Words thrilled him. He knew the canon — he was far better read than me — but his favorite poet was Stevie Wonder. Movies thrilled him even more; he studied “the picture business” endlessly and had enough screenwriting gigs to join the Writers Guild. The harder times got, the more he believed he was coming close to cracking open the kind of opportunity only Hollywood could offer to a panoramic thinker like Eric Priestley. In his mind it was inevitable. It was not.

Like most romantics, he was a tension of opposites. Eric was hard-nosed and hardworking, dedicated every day to putting down ideas for stories, movies, pilots and commentary. At the same time, he could be stubbornly naïve about how the world worked, and what he could realistically do; one of his many aborted schemes was applying to work as an intelligence analyst for the State Department.

To support his writing, he was a bricklayer, a handyman, occasionally a writing teacher. He stayed close to his fellow Watts Writers alums — the poet Ojenke, the writer and professor Quincy Troupe and Kamau Daáood, who co-founded the World Stage in Leimert Park — but he wasn’t a “community” figure. He was simply too busy trying to figure it all out for himself.

Eric stayed furious. He never resigned himself to the enduring nature of racism and injustice. Of course, that angst was another aspect of his romanticism, his better expectations. It lived side by side with the undimmed joy and gregariousness that defined him to those he knew.

“His incredible true love of words, that was his salvation,” says his good friend and fellow screenwriter Tommy Swerdlow. “He really believed in the written word.”

He believed in his own words. Another friend and a writer Eric mentored, Pam Ward, read him verses from “Abracadabra” over the phone in their last conversation. Eventually he joined in, reciting the lines from memory. It lifted his spirits at a crucial moment, Pam said, because it made him remember what he already knew: His many words, and the anxious but exhaustive search for meaning and justice that animated them, would live forever. Fame.

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.