Op-Ed: The West owes a centuries-old debt to Haiti

- Share via

The treatment of Haitian refugees at the U.S. border last month — some chased by horseback agents, others huddled by the thousands under a bridge — is tragic. For reasons that are less obvious, it is also ironic. Although Americans’ centuries-long debt to the Haitian people is untaught in our schools and unacknowledged in our public discourse, the indomitable spirit of the Haitian people created the United States we know today.

Even the capsule version of Haiti’s successful fight to end slavery and for independence at the turn of the 19th century is riveting. C.L.R. James, the late Trinidadian political leader and historian of the Caribbean, wrote six decades ago:

“In August 1791, after two years of the French Revolution and its repercussions in [Hispaniola], the slaves revolted. The struggle lasted for 12 years. The slaves defeated in turn the local whites and the soldiers of the French monarchy, a Spanish invasion, a British expedition of some 60,000 men, and a French expedition of similar size under Bonaparte’s brother-in-law. The defeat of Bonaparte’s expedition in 1803 resulted in the establishment of the Negro state of Haiti which has lasted to this day.”

It’s one of the most remarkable stories of liberation that we have as a species: the largest revolt of enslaved people in human history, and the only one known to have produced a free state. But even this sweeping account understated the extraordinary role that Haiti’s rebellious enslaved played in world history.

Their success in freeing themselves in the face of the stoutest European hostility imaginable ironically made Haiti the first nation to fulfill the most fundamental values of the Enlightenment: freedom from bondage and racial equality for all. These principles were enshrined in Haiti’s first constitution, in 1804, decades before they were embraced by the United States.

And that was just the beginning.

Seeds of greatness

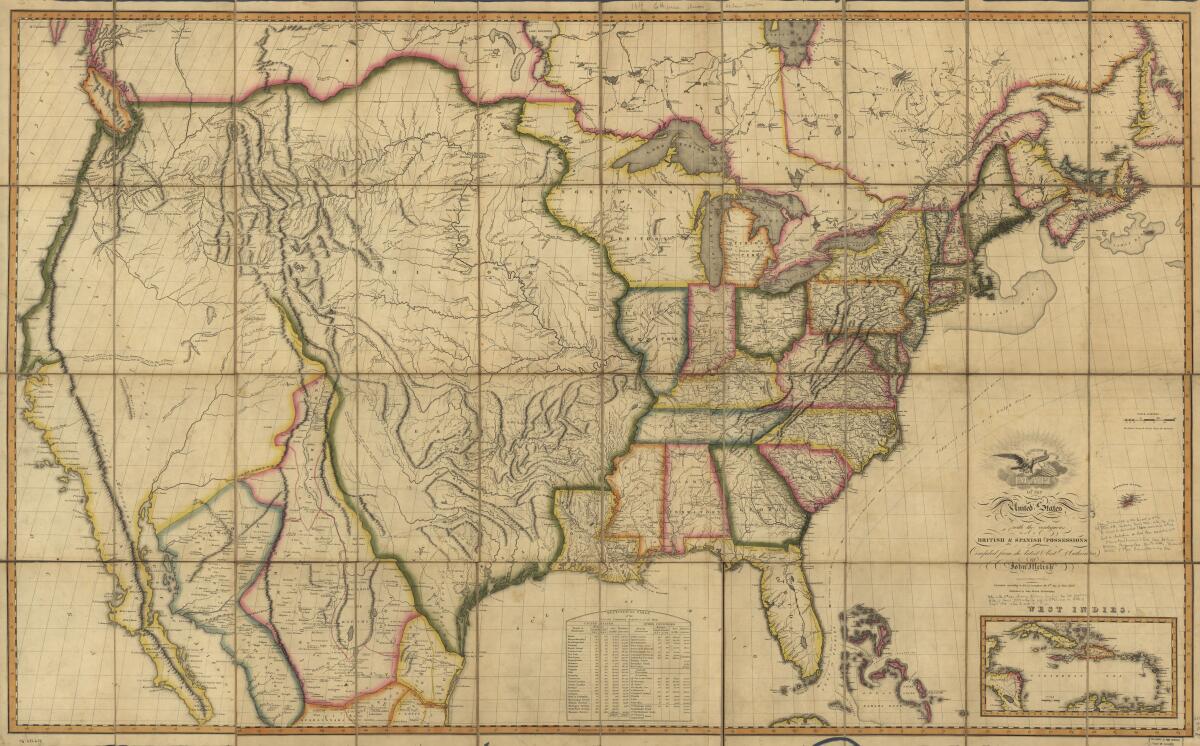

The Haitians’ defeat of Napoleon forced the French dictator to sell off his vast holdings in continental North America to the young United States. This was done at the fire-sale price of $15 million, and with a stroke added the land that today comprises all or part of 15 states. The Louisiana Purchase transformed the country from a vulnerable, coast-hugging collection of former English colonies to a continental power.

Napoleon exclaimed in defeat: “Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies!” Robert Livingston, one of Thomas Jefferson’s negotiators in Paris, was as exuberant as the dictator was dejected. “From this day the United States take their place among powers of the first rank,” he correctly assessed.

Black Haiti’s defeat of France opened up the Mississippi Valley to large-scale westward migration — by white farmer settlers and by huge numbers of Black people who were enslaved in the Old South after they or their ancestors were shipped there in chains from Africa. Now, in a second great forced migration, these enslaved people were quickly put to backbreaking work growing cotton. On the basis of Black sweat and blood, production of this fiber soared, coming to account for two-thirds of America’s exports at its peak, by the eve of the Civil War.

America rose swiftly on the back of cotton exports produced by the enslaved in the Mississippi Valley, and on a boom in ancillary businesses that profited from it, from northern banking to railroads — all because, on a Caribbean island in 1791, Black people demanded freedom.

The impact of the Haitian Revolution was just as dramatic on the other side of the Atlantic, especially for Britain.

We are accustomed to thinking about Britain’s rise during the Industrial Revolution as a tale of mechanical ingenuity and enterprise. But no less than America’s, that country’s boom was predicated on slavery in the Mississippi Valley.

At a 19th century peak, while 1 in 13 Americans worked to produce cotton, a number that consisted overwhelmingly of the enslaved, 1 in 6 Britons worked in textiles. Make no mistake: Textiles meant cotton, the one indispensable ingredient of the Industrial Revolution. Cotton meant the Mississippi.

A historical irony

That history may not be front of mind when we see news coverage about Haitian refugees and the U.S. Border Patrol. But it suffuses the imagery and the language whenever Haiti is the topic.

As scarcely anyone with a television or a social media account could have missed, for the first time since the border has become a front-line political issue in this country, refugees were chased last month by Border Patrol agents on horseback, as if they were cattle being herded in a Hollywood western. In the most infamous images, these agents ran down Black men while wielding leather reins that bore a painfully close resemblance to lashes.

The symbolism of Americans corralling Haitian refugees could hardly be more tragic or ironic. Haiti not only bequeathed the world historical events laid out above, but also, with nearly a million enslaved Africans brought to the island after 1680, was one of the premier sites in the development of chattel slavery as an institution in the so-called New World. The word “chattel” directly derives from “cattle” and describes a system in which humans are reduced to bestial property, put to work however their owners deem proper, stripped of all rights — even those associated with parenthood, because the offspring of enchattled people automatically became the property of the parents’ masters.

The appalling scene at the border offers us a rare opportunity to rethink the shared Western debt to Haiti for its extraordinary role in our history. The refugee crisis is itself a chance for Americans to live up to the ideals of the Haitian Revolution.

‘Poorest nation’

As a former longtime foreign correspondent for the New York Times, I know that I have played a role myself, however unwitting, in the journalistic reductionism that has helped erase Haiti’s place in the rise of the West and the expansion of the United States.

I covered the country for four years in the early 1990s, traveling there countless times, and sometimes spending weeks at a time in Haiti during a period of prolonged and severe political turmoil and violence. A phrase that sometimes slipped into my coverage, and appears to this day in other writing about Haiti, served as a kind of code to condense the country’s history into the briefest journalistic shorthand. It also rendered Haiti’s real story invisible, and took Western powers and people off the hook. That phrase was “poorest nation in the Western hemisphere.”

As true as this was in narrowly factual terms, it told us nothing about how Haiti had come to be, about its blood contribution to Western wealth. It silenced the immense gift to American geography that its revolution had made possible. It said nothing about the fierce opposition to Haitian freedom mounted by American founders like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, whom we celebrate as avatars of Enlightenment values and democracy.

Both men saw the prospect of Black freedom in Hispaniola as a source of nightmarish horror that would threaten the tranquility and prosperity of white people by undermining slavery in the United States. And while Jefferson spoke of an expansionist America as an “empire of liberty,” even as slavery spread westward, Haiti’s revolutionary leaders took that very same language and enshrined it in their constitution, immediately giving it universal substance.

“It is not circumstantial liberty conceded only to us that we want,” wrote Haiti’s most important revolutionary leader, Toussaint Louverture, who had been formerly enslaved. “It is the absolute acceptance of the principle that no man, whether born red, black or white, can be the property of another.”

The press’ reductionist characterizations of Haiti also whistle past the crippling indemnity, the equivalent of $21 billion, that France imposed on Haiti in 1825, before Paris would recognize the young nation’s independence. And they ignore the history of deep American interference in Haiti’s affairs, including a military occupation, which lasted from 1915 to 1934.

“Poorest nation” indeed. No wonder Americans and Europeans would elide the causes of that poverty.

Fight for freedom

I am being tough on my own profession, but teachers of American and world history have done even worse.

In securing freedom for a population of former slaves, Haitians fought “as naked as earthworms,” in Louverture’s famous phrase, successively defeating the three strongest imperial powers of the age: Spain, Britain and France. Those latter two countries sent the two largest naval expeditionary forces in their histories up to that point to try to reimpose slavery on Hispaniola’s Black population in order to control the global supply of sugar. Each was defeated, and the details of this history go as unacknowledged in French and British classrooms today as Haiti’s role in the Louisiana Purchase and the rise of King Cotton do in American ones.

Louverture explained his armies’ successes in language as noble as any that emanated from America’s own Revolution: “We are fighting that liberty — the most precious of all earthly possessions — may not perish.”

As we watch Haitians sacrificing everything to make their way to this country, we should do so not only with more empathy, but also with the understanding that liberty is as integral to their story as it is to our own. What is more, their liberty is a vital part of our own story.

Howard W. French, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, is the author most recently of “Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War,” set to be published Tuesday.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.