Op-Ed: Everyone should mask up, because kids aren’t vaccinated

- Share via

The official guidance for COVID-19 safety is becoming more chaotic by the day. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that only the unvaccinated need to wear masks, but the American Academy of Pediatrics urges everyone to do so. California is requiring people to cover their faces at school, and Los Angeles County went even further with a full indoor mandate. Meanwhile, other states are banning or discouraging mask rules.

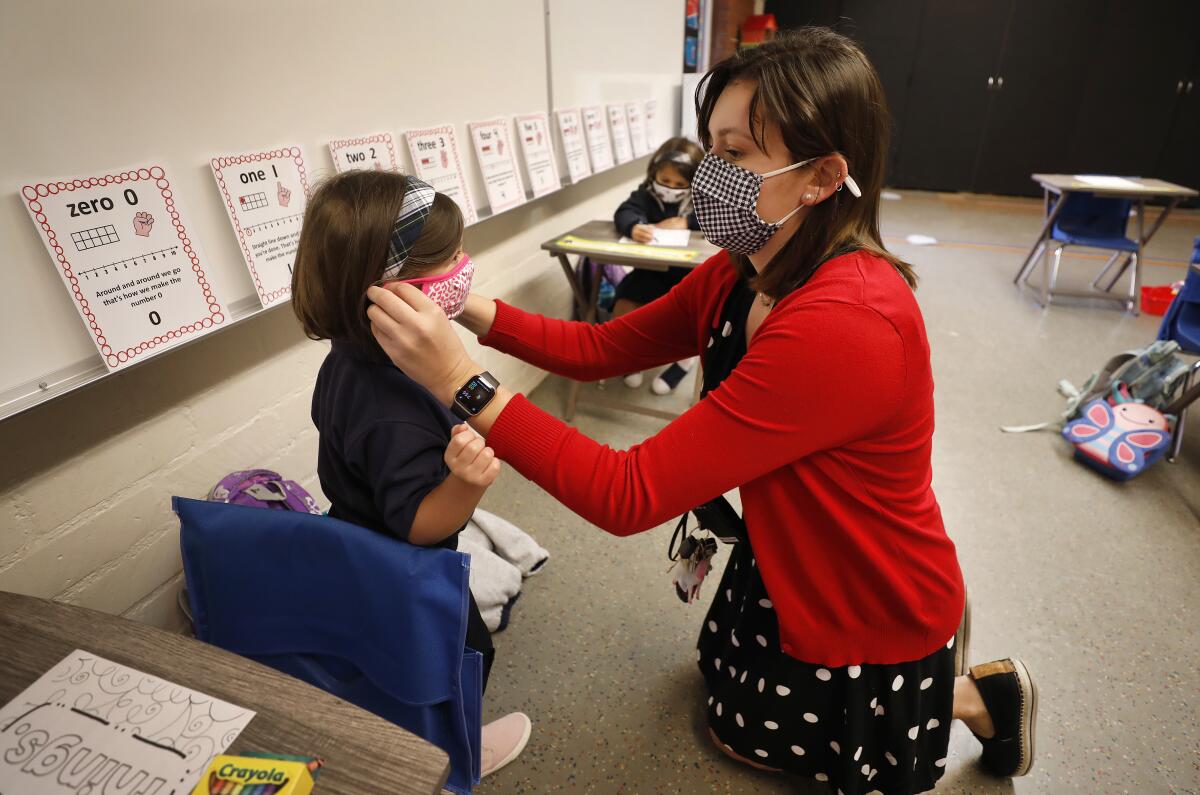

As the school year approaches and children under 12 remain ineligible for vaccination, this chaos is downright dangerous.

The answer is simple: The CDC urgently needs to reinstate mask recommendations for everyone.

Without clear, uniform guidance from the top, patchwork implementation of masking across the U.S. will leave many, if not most, children vulnerable.

And they are highly vulnerable.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, news reports have emphasized that older adults are at the highest risk of death and serious illness, and that children are spared the worst effects of COVID-19. This is true. It’s also true that nearly 500 children have died, 150,000 to 240,000 have likely been hospitalized, and more than 4,000 have developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome. At the same time, only one child has died of the flu. Based on these measures, COVID-19 is more than 400 times more deadly than the flu and is one of the leading causes of death or hospitalization in children.

With public safety measures lifted and most Americans going unmasked indoors, it is only reasonable to assume that infection rates, hospitalizations and deaths will rise. This is particularly true because of the Delta variant, which may be more than twice as transmissible and has a viral load more than 1,000 times greater than the original strain.

Yet even these numbers don’t touch upon the long-term devastation that COVID-19 may cause. Like adults, children can develop long-haul COVID, with studies reporting between 2% and 42% of patients suffering lasting effects. Even the lowest predictions around 2% (or 1 in 50) are unacceptably high, and the true rates are likely higher. Indeed, the British National Health Service is reporting numbers of 7% to 8% and is opening 15 pediatric clinics for long-haul COVID across the U.K. We may see a similar need for such clinics if the CDC doesn’t change its stance.

The symptoms of long COVID in children are wide-ranging and can be incapacitating. Some of the most common include fatigue, headaches, muscular pain, heart palpitations, chest pain, abdominal pain, fever and nausea. Rarer, more dangerous reported symptoms include nerve pain, liver damage, paralysis and seizures. Many neurocognitive symptoms have also been reported; they include difficulty concentrating or processing information and impaired memory. Most children had multiple symptoms, which could last for months and be constant or recurring.

Though many children did improve, others continue to suffer. A British survey of over 500 children found that only about 10% were able to return to normal levels of activity. There could be many other effects that we will discover only in the months, years or even decades to come. Indeed, reports are now surfacing that coronavirus infection may lead some children to develop diabetes.

The rapid rise of the Delta strain makes public safety measures like masking more urgent and necessary to protect children from the known and unknown effects of infection. This is particularly true given that vaccinated people can become infected and transmit the Delta variant, even if they are outdoors.

The CDC continues to insist that vaccination is a choice and that only the unvaccinated need to worry about the Delta strain. But who is unvaccinated? Every child under the age of 12, because they have no choice. They depend completely upon adults for protection. If the CDC won’t recommend masks for everyone, then cities, counties and states should.

Karolina Corin, a biological engineer, is a research scientist at UCLA studying membrane proteins.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.