Op-Ed: How could originalism produce a revolution for gay and transgender rights?

- Share via

The Supreme Court’s holding on Monday in Bostock vs. Clayton County presents a rich puzzle. A 6-3 majority found that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status. How could an avowedly originalist court — one committed to interpreting laws according to the “original public meaning” of the text — arrive at such a progressive, even revolutionary result?

Originalism is widely considered to be a doctrine that opposes evolution in the law, insisting that statutes and the Constitution are fixed and immutable, frozen at the time the laws were written. Former Justice Antonin Scalia championed the standard. To quote his memorable war cry, the Constitution is “not a living document. It’s dead, dead, dead.”

But on Monday originalism delivered a sea change in Title VII’s admonition against “discrimination because of sex.” The law nowhere mentions transgender or gay people. Yet Justice Neil M. Gorsuch’s majority opinion nonetheless finds in the language a very 2020 idea: People shouldn’t lose their jobs just because they’re transgender or gay.

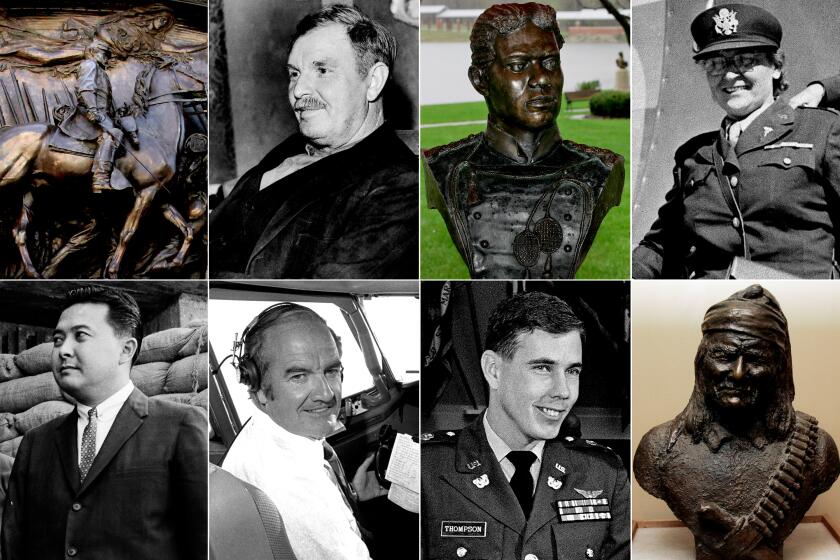

Take the names of traitor generals off Army posts and replace them with these 10 honorable soldiers.

Gorsuch didn’t get there by abandoning originalism. Indeed, his decision is a classic example of interpreting the law according to the “original public meaning” standard. He consults and cites 1964 dictionaries for definitions of Title VII’s key terms — “sex,” “because of” and, especially, “discriminate.” The settled meanings of these words, the decision points out, haven’t changed in the last 56 years.

And in the judgment of the court, those definitions can add up to discrimination against gays and transgender people. For example, if an employer intentionally treats a man worse for actions the employer would tolerate in a woman (being married to a man, for instance), the law has been broken.

Gorsuch’s reasoning entails filtering out — indeed, dismissing as “irrelevant” — what the legislators may have thought they were doing when they wrote Title VII in 1964. “The people are entitled to rely on the law as written,” he writes, “without fearing that courts might disregard its plain terms … even if the legislature that passed the law didn’t grasp its full implications” (emphasis added).

The decision’s self-described “straightforward” conclusion delivers a huge political victory for progressives, a social watershed of the sort conservative judges, including Gorsuch, usually say should be left to a legislature. Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who wrote one of two Bostock dissents, sounds almost incredulous that an interpretive methodology that says the law’s meaning was fixed in 1964 could produce such a 2020 outcome. He points to 30 previous court decisions that expressly found that Title VII’s language did not apply to gays and transgender people.

So how do we square the 180-degree reversal Bostock represents with the core conviction of originalism, that the meaning of the law does not “evolve”?

It goes back to what Gorsuch said about the benighted 1964 Title VII legislators. They — and the judges in Alito’s examples — simply didn’t get it; they failed to grasp the full implications of the law’s words and the reach of its operative principle. Perhaps clouded by the same prejudice that generally infected society in 1964, they were unable to recognize that prohibiting discrimination “because of sex” amounts to this: “An individual’s homosexuality or transgender status is not relevant to employment decisions.”

The decision in no way contradicts originalism’s core conviction: The meaning of the text didn’t change, only the depth of our understanding of it.

If this all sounds like legal gamesmanship, consider another example of a sweeping originalist reversal that is as solid an interpretation of law as exists in American jurisprudence: Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 decision that outlawed school segregation. It’s well established that the members of Congress who passed the 14th Amendment would never have dreamed that its enactment could forbid separate schools for Black and white children; indeed, in a time when segregation was by and large taken for granted, they would have been horrified at the thought.

No matter. Though it took the Supreme Court nearly 100 years to grasp it, the words of the 14th Amendment and the principle of racial equality it enacted were — and had always been — incompatible with racial segregation in schools.

As it turns out, for Gorsuch, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and the four liberal members of the court who make up the Bostock majority, the drafters of Title VII were far more progressive than they or Alito’s 30 subsequent courts realized. The words they wrote called for an end to workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. It just took a few generations for the Supreme Court, and society, to discern it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.