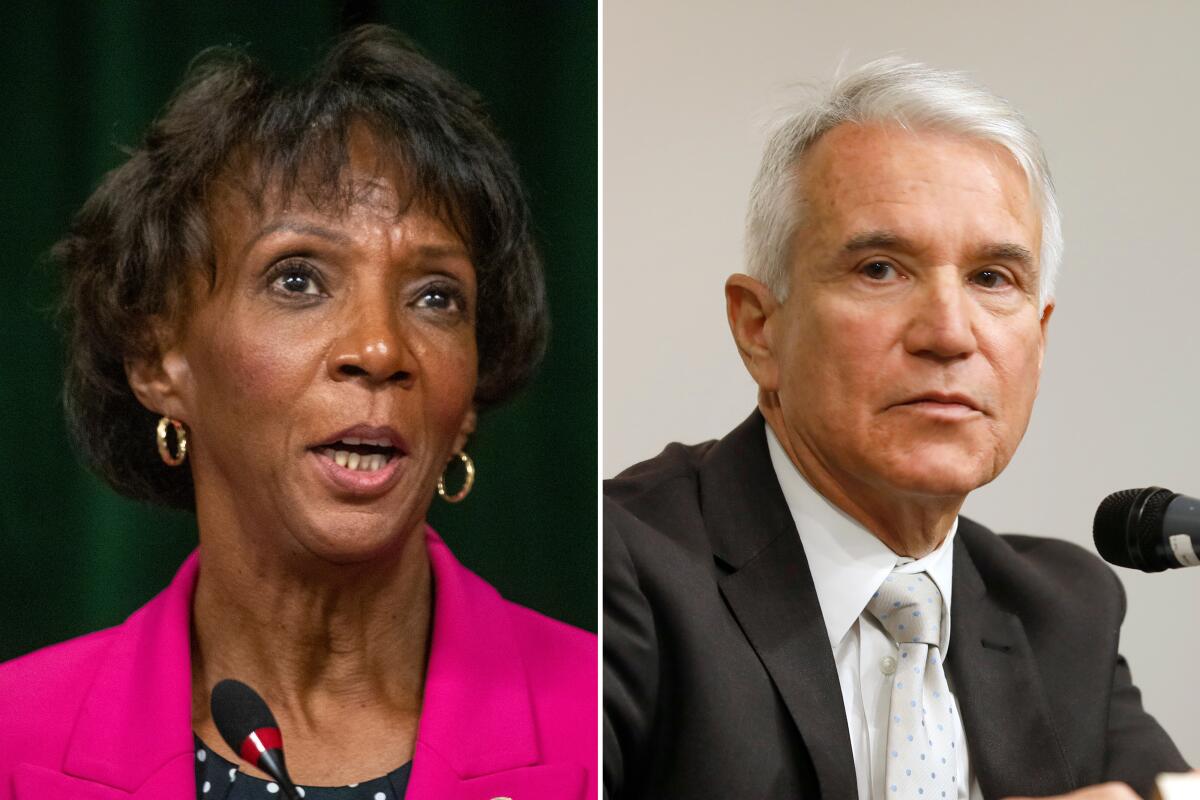

Editorial: George Gascón must demonstrate that he is the true justice leader L.A. County needs

- Share via

Jails and prisons are the perfect breeding ground for disease, with inmates packed so tightly they cannot possibly observe the social-distancing rules meant to stem the spread of the coronavirus, the contagion that has already sickened more than 300,000 people in the United States. The nation’s largest single source of infections — more than any cruise ship or nursing home — was Chicago’s Cook County Jail until it was overtaken this week by Ohio’s Marion Correctional Institution. Other jails and prisons threaten to surge even further ahead.

The nation’s largest jail, though, is in Los Angeles County, where the sheriff took early action to reduce by about 600 the astoundingly large inmate population of more than 17,000. The Board of Supervisors called for quick studies and efforts to get the number down even further. Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey has been, at best, along for the ride, finally agreeing last week not to jail people accused of low-level crimes who could be safely released on their own recognizance, just before “zero-bail” became the Judicial Council’s statewide mandate in all California counties. The L.A. County jail population currently hovers around 13,000 — still large, still crowded and still susceptible to an outbreak on the order of Cook County’s. At present, the L.A. jails have nearly 400 staff and inmates quarantined or isolated for possible exposure.

Sheriffs run the jails and officially manage inmate populations, but to a large extent the jailhouse gate is operated by district attorneys. D.A.s are the ones who decide whether a defendant should be freed before trial or sent before a judge to seek release on bail. D.A.s decide what crimes to charge, what sentences to seek and what plea bargains to accept. More than sheriffs, judges and defense lawyers, district attorneys determine the size and composition of the jail and prison population.

As the virus began hitting the U.S. hard, dozens of district attorneys in other jurisdictions began reducing their jail and prison populations to permit safer conditions for staff and for inmates who remained behind. D.A.s asserted their leadership, taking responsibility for the lives of inmates and the welfare of their families and communities and, by extension, all of us who are affected not only by crime but by a contagion that respects no boundaries between the incarcerated and the free.

COVID-19 was only just becoming a concern for voters who cast ballots for Los Angeles County district attorney in the days leading up to and including the March 3 primary. In early returns, Lacey was collecting slightly more than the 50% threshold needed to avoid a runoff for a third term. But by the end of the month, as L.A. County residents were sheltering in place and as the primary results were certified, Lacey’s share of the vote in the three-person race had slipped, and it had become clear that challenger George Gascón would face her in November.

A runoff is welcome. In her two terms Lacey has been a workmanlike district attorney but not a leader. During the coronavirus crisis, when time is of the essence, she has moved too slowly, mirroring her work on other matters in the years before the pandemic. She has failed, for example, to adequately meet the early promise of her initiative to divert defendants with mental health problems out of the criminal justice system and into treatment.

Old tough-on-crime presumptions and practices have been left behind by D.A. offices in Philadelphia, Chicago, Baltimore, San Francisco and numerous other jurisdictions, but not so in Los Angeles. That’s ironic, because L.A. County — the nation’s largest criminal justice jurisdiction — is on the cusp of replacing many gratuitously punitive measures with a public health and mental health approach to justice. The effort was spurred by community activists and criminal justice reformers and embraced by the Board of Supervisors. The D.A. has been involved, but she has not led. The Los Angeles district attorney’s office largely persists in policies that result in clogged jails and prisons — and, not incidentally, high recidivism, broken families, unequal justice and unhealthy communities.

More voters cast their March ballots for former San Francisco D.A. Gascón and former federal deputy public defender Rachel Rossi than for Lacey, but that by no means ensures Gascón a path to victory in November. It’s a different world today than it was during the primary election and will be far different still in seven months when the final round of voting by mail begins. He must earn the trust of Rossi supporters, many of whom sought an even greater overhaul of the justice system.

For Gascón to become the leader L.A. County needs, he must lead now. He must articulate, in a clearer and more comprehensive way than he has done so far, his vision for a modern criminal justice system, and how it will promote greater fairness, justice, public health and — let us never forget — safety for all of us.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.