A victory for gays but a loss for lawyers

- Share via

Is it good news that a federal appeals court has ruled that lawyers may not challenge prospective jurors because of their sexual orientation? Yes and no.

Tuesday’s decision by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a jury verdict in a federal antitrust trial that involved an AIDS medication, because a gay prospective juror was struck by a lawyer using a peremptory challenge. Traditionally, a peremptory challenge — unlike a challenge “for cause” — can be used to excuse a prospective juror for any or no reason, even if the lawyer making the challenge is acting on a hunch. (A district attorney might not want a priest on the jury in a criminal trial because clergymen are prone to forgive.)

But in 1986, the Supreme Court ruled, somewhat paradoxically, that while a lawyer could use a peremptory challenge to strike a prospective juror for no reason, he or she could not use it for any reason. Specifically, peremptory challenges couldn’t be based on the prospective juror’s race. The principle of that decision, Batson vs. Kentucky, was later extended to peremptory challenges based on gender.

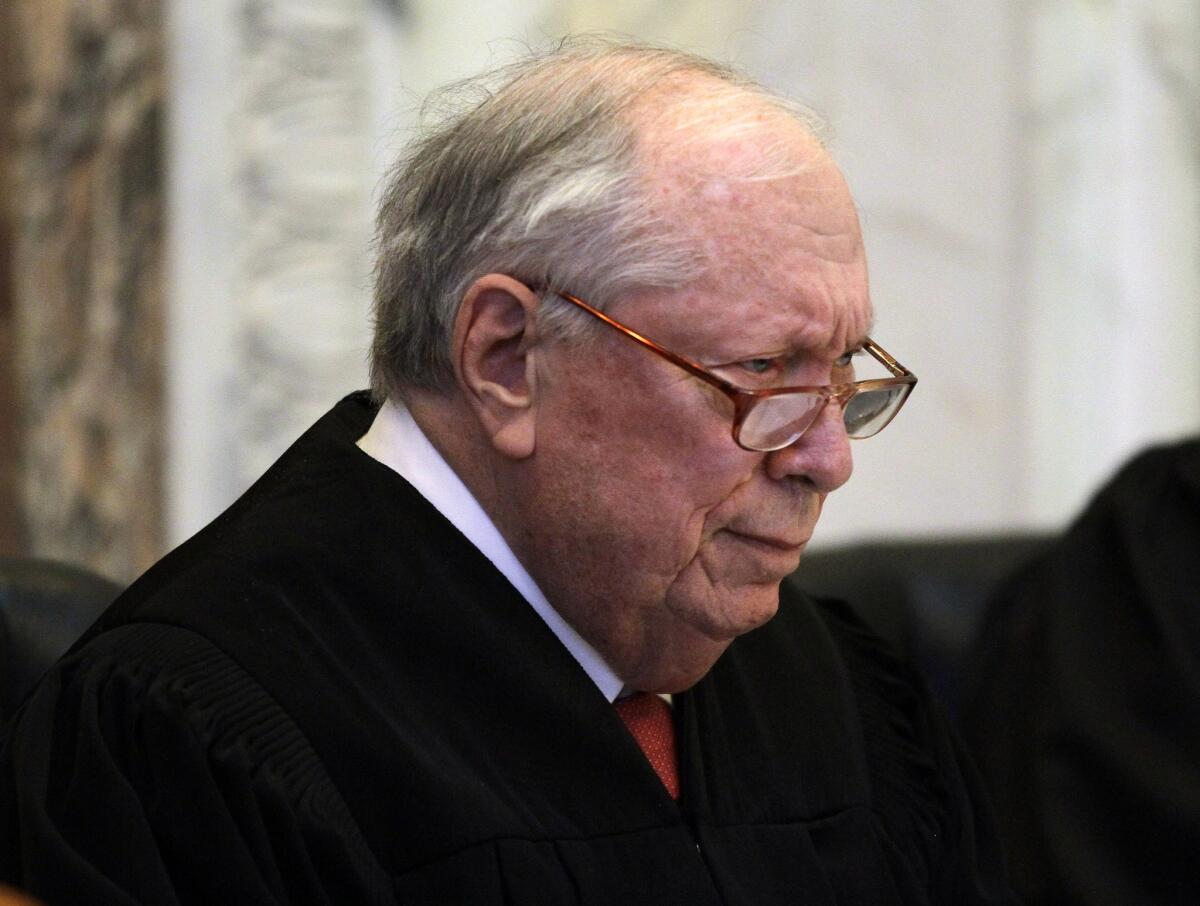

In Tuesday’s decision, the 9th Circuit extended the Batson principle further to bar peremptory challenges based on sexual orientation. Judge Stephen Reinhardt wrote: “Strikes exercised on the basis of sexual orientation continue [the] deplorable tradition of treating gays and lesbians as undeserving of participation in our nation’s most cherished rites and rituals.”

As a ringing endorsement of gay rights, Reinhardt’s statement is welcome. But the decision, by adding yet another exception to the use of the peremptory challenge, turns the challenge into the legal equivalent of Swiss cheese.

And there’s another problem, as The Times noted in an editorial about this case.

Even though lawyers may not use peremptory challenges motivated by a concern about the prospective juror’s race or gender (or, now, sexual orientation), the lawyer can still strike the juror by offering a “neutral” explanation for the challenge — one based on, say, the prospective juror’s age, attire or occupation.

So if peremptory challenges aren’t really peremptory anymore, and if lawyers can disguise their improper motives for making them, why not get rid of the peremptory challenge altogether? That’s what Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer has suggested. It’s a good idea.

ALSO:

The ‘ax’ versus ‘ask’ question

How to make lethargic L.A. grow

Sochi suicide-bomber threat: The Olympics aren’t worth it anymore

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.