Opinion: Religion makes a comeback in the ‘gay wedding cake’ case

- Share via

When Masterpiece Cakeshop vs. Colorado Civil Rights Commission — better known as the “gay wedding cake case” — first attracted national attention, it was viewed as a battle in the culture war between gay rights and religious freedom.

But religion was only part of the story.

In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Christian baker Jack Phillips complained that being ordered to sell “custom” wedding cakes to same-sex couples violated his right to free exercise of religion.

But Phillips also argued that his free-speech rights were violated because he was being compelled to “speak” in favor of same-sex marriage through the artistry of his cake “creation.”

In the run-up to Tuesday’s oral argument, Randy Barnett, a law professor at Georgetown University, suggested that this other dimension of the case would “get the most attention.”

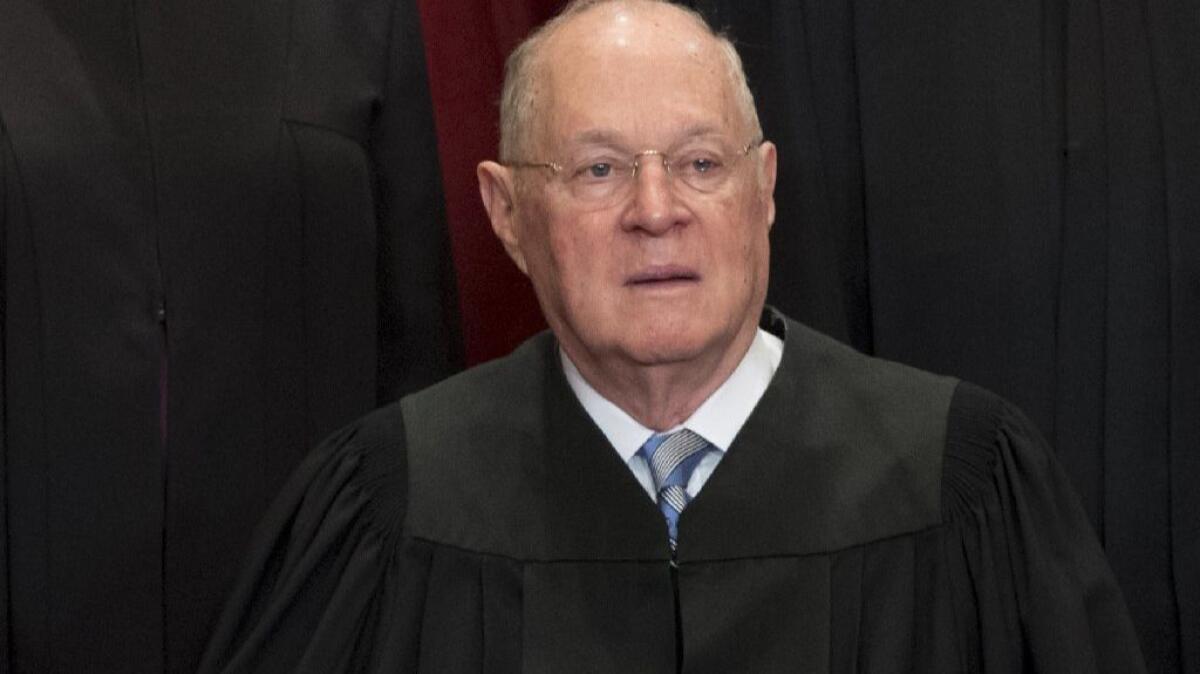

But after the argument, Barnett tweeted that Justice Anthony M. Kennedy — who is generally expected to be the deciding vote in the case — “did not seem receptive to compelled speech theory. Instead, he said the state ‘has been neither tolerant nor respectful of baker’s religious faith.’ ”

The justices didn’t ignore the question of whether Phillips is engaged in protected speech when he bakes a wedding cake. Indeed, they spent considerable time trying to pinpoint which occupations associated with weddings are “expressive” enough to enjoy free-speech protections.

Justice Elena Kagan asked Kristen Waggoner, Phillips’ lawyer, if a hair stylist would qualify. She responded, “Absolutely not.” But Kagan replied, “Why is there no speech in creating a wonderful hairdo?”

Still, the issue of religious liberty made a decided comeback at Tuesday’s argument. Kennedy told Colorado Solicitor Gen. Frederick Yarger that “the state in its position here has been neither tolerant nor respectful of Mr. Phillips’ religious beliefs.”

Kennedy and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. deplored a comment by a member of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission that ruled against Phillips that “religion has been used to justify all kinds of discrimination throughout history,” including slavery and the Holocaust.

Picking up on a point made in Phillips’ brief, Alito also questioned Yarger about the fact that Colorado authorities hadn’t punished bakers who had refused to bake a cake with a message opposing same-sex marriage. Alito noted that complaints of such denial of service had been filed by “an individual whose creed includes the traditional Judeo-Christian opposition to same-sex marriage.”

It wouldn’t take too ingenious a lawyer to reframe a baker’s refusal to bake an anti-same-sex marriage cake as an act of religious discrimination in violation of Colorado’s public accommodations law. That would support Phillips’ claim that the state’s enforcement of the law has been biased against believers.

A finding for Phillips on religious liberty grounds would be complicated by a 1990 decision in which the court held that a religious motivation doesn’t entitle a believer to disobey a generally applicable law.

But in their brief, Phillips’ lawyers cite a decision from 1993. It said that states violate the Free Exercise Clause when they engage in hostility toward religion even if it is “masked” by a statute that seems neutral on its face. Phillips’ lawyers suggest that the way he was treated by the Colorado Civil Rights Commission was an example of such hostility.

If the court were to rule for Phillips on his religious freedom claim — rather than on the grounds that he had been forced to engage in “compelled speech” — it wouldn’t have to waste much intellectual energy on deciding which creative functions associated with a wedding qualify as “speech.”

Such a decision, as Barnett has suggested, might also be more limited because it would be confined to the facts of the Colorado case.

But it would still be viewed as a victory for opponents of same-sex marriage. That is something Kennedy, the author of the majority opinion in the 2015 decision enshrining marriage equality, must remember as he ponders how he will vote.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.