Op-Ed: Never mind SARS or MERS, worry about measles

- Share via

As Americans head off on summer vacations this year, federal health authorities are keeping a wary eye out for an unwanted traveler: one of the most contagious infectious diseases in the world.

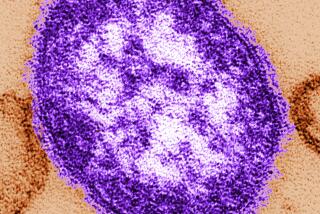

The microscopic droplets that spread this virus can remain suspended in the air for up to two hours, and virtually all of those without immunity who are exposed will catch it. Most of those who become ill will, after an incubation period that ranges from eight to 12 days, develop a fever and a characteristic rash. Some patients, with children being the most vulnerable, will develop pneumonia or encephalitis, which can lead to brain damage or death.

I’m talking about measles.

This potentially fatal, vaccine-preventable infectious disease was practically eradicated in the U.S. a decade ago, thanks to high vaccination rates. But in May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a sobering report of a dramatic uptick in measles cases in the U.S. this year. Some 539 cases have been reported as of June 27, according to the CDC, the highest number in 20 years. In 2011, which had the second-highest number of measles cases in recent decades, the CDC reported fewer than 200 cases for the entire year.

Other parts of the world are seeing even larger outbreaks, and there is a growing concern that Americans returning home after overseas vacations will push the numbers here higher too.

Screening of air travelers for infectious diseases is impractical and ineffective, as the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009-10 demonstrated. In part, this is because passengers can be contagious with an infectious illness long before they are symptomatic.

If all this sounds frightening, it doesn’t have to be — at least where measles is concerned. A simple, safe and effective vaccine conveys immunity to most who receive it.

But a persistent mistrust in vaccinations has led to pockets of the un-immunized, despite the extraordinary success and safety of childhood vaccination. Thousands of parents on both sides of the Atlantic continue to refuse or delay selected vaccines, including the one for measles.

In California and Vermont, for example, the number of incoming kindergartners fully immunized against measles dropped from 93% in 2005 to 83% in 2010. And this isn’t just a problem at the low end of the socioeconomic spectrum. One public school in Malibu, for example, reported to the state that more than 40% of its kindergartners weren’t fully vaccinated.

A recent commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine by Dr. Douglas Diekema pointed out that although some parents object to immunization on religious or philosophical grounds, many don’t vaccinate their children because they believe that the benefits of immunizations don’t justify the risks. This is totally unsupported by scientific and clinical evidence.

In a sense, immunization programs have been a victim of their own success. Because of vaccinations, Americans today have little experience with vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles. As a result, they cannot easily appreciate the benefits of vaccination or the risks associated with not vaccinating.

The challenge from a public health standpoint is to figure out how to disseminate that knowledge more effectively. We need to redouble our efforts. One important step would be for state and federal public health agencies to undertake a robust social networking and media campaign on vaccinations. This shouldn’t be too difficult. The CDC, for example, has excellent information on its website about the risk of measles during this travel season, but the information is not readily available on social media and is likely to be missed by most travelers.

When new diseases such as MERS or SARS pop up, travelers besiege doctors with questions about how they can protect themselves and their families. But some of those same people are failing to take time-tested precautions against more familiar killers like measles. Each one of us is a stakeholder in community and global health. And in this era of globalization, when people fly frequently to distant parts of the world, infectious disease threats can occur overnight and without notice. We owe it to our children and our communities to protect ourselves.

Dr. Mark Gendreau is the vice chairman of emergency medicine at Lahey Hospital & Medical Center and an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Tufts University.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.