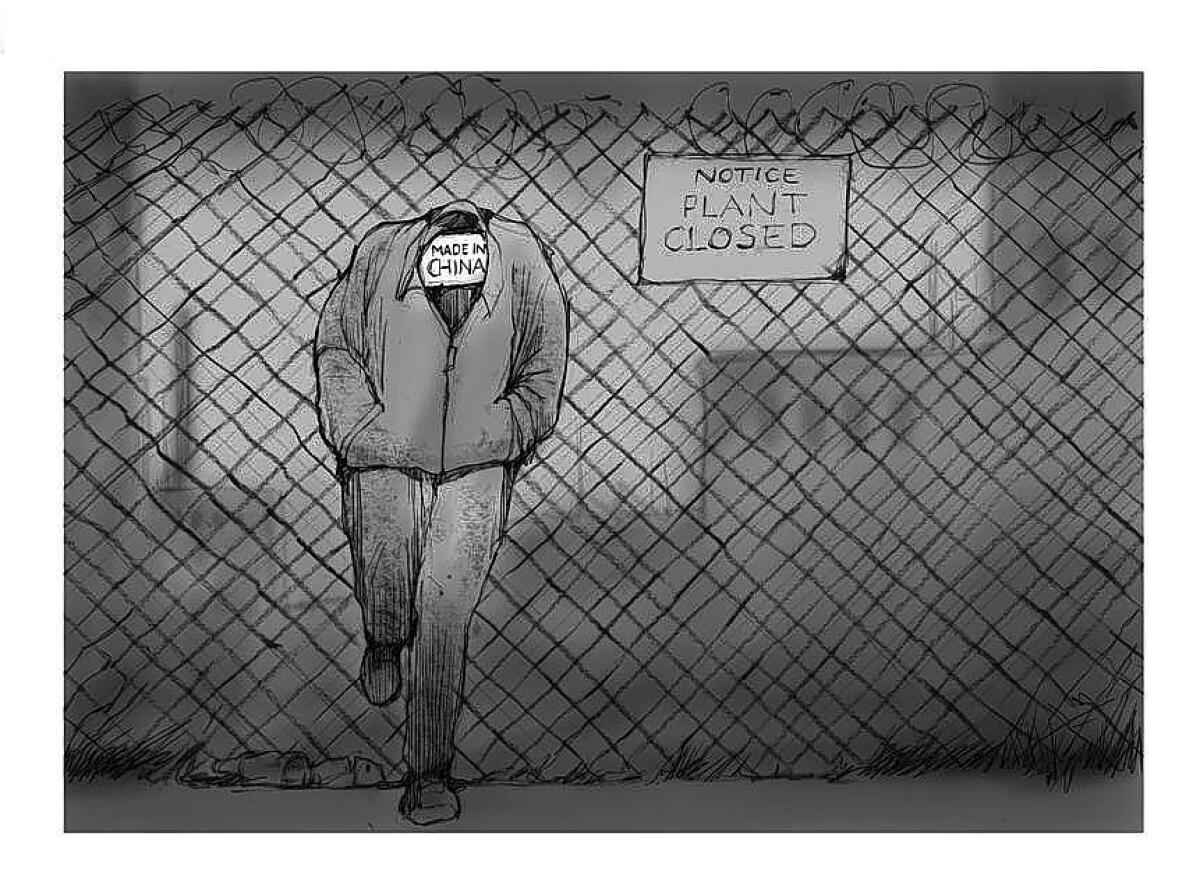

Where the jobs are

- Share via

A friend recently got stuck when he tried to explain to his son, who was struggling to find a job, how our economy got to be the way it is. He asked my help since I am a well-known crank on the matter. I offered him three short anecdotes:

Last summer I was in a Home Depot standing in front of a veritable mountain of new air conditioners. They were all from China, which was no surprise. But to be annoying I asked a passing clerk where they were made. He was a young man, hired more for the spring in his step than his knowledge of international sourcing. We both looked at the boxes, piled in a pyramid, eight levels high. The boxes didn’t say anything about China. But they did say “Made in PRC.”

“Are these from China?” I asked.

He paused a moment. “No, they’re from Puerto Rico.”

Or consider this example from last month: A textile factory in Italy caught fire and seven workers were killed. They were all imported Chinese nationals working for Chinese companies operating in Italy so they could put a “Made in Italy” label on their cloth.

A third example: The city of New York decreed a few years ago that each bedroom in the city must have a carbon monoxide detector. There are roughly 11 million bedrooms in New York City, so the law created a huge market. Further, the devices have a life of five years, after which they must be replaced, so the continuing market was also guaranteed. A manufacturing enterprise could hardly find a surer customer base.

But was there a rush of companies here in the United States gearing up to manufacture 11 million devices for this guaranteed sale? No. Almost all the detectors were made in China or Taiwan.

Over the last 20 years, countries around the world have ditched their communist governments, or at least turned their backs on strict communist economic principles. At the same time, India and other Asian nations have rapidly moved into global trade. This has meant billions more workers around the world competing with American workers to make stuff and offer services. At the same time, shipping has become more efficient and economical, and international communication has become cheap, instantaneous and simple. And since the international workers are willing to accept extremely low wages, they have the advantage. Around the world, subsistence farmers have transformed themselves into subsistence factory workers.

And during this entire period, what did the United States government do to meet this challenge? Nothing. Our clueless, bellowing national leaders from both parties took no action to meet the effect of this new competition. Many American companies embraced the changes, happy to make profits off underpaid Asian workers while allowing huge swaths of American industry to die.

Two observations are often made to justify this disruptive period. The first is that the situation is an inevitable outgrowth of globalization and natural economic laws. In this scenario, nothing that the foreign manufacturers have done to U.S. workers differs from what American manufacturing did to the older economies in Europe. Lower costs and cheaper goods will always gain market share. Sometimes that share will be 100%.

A second explanation holds that what we are seeing is the necessary cost of the death of communism. Under this logic, communism was held in place by violence and oppression, and sooner or later it would have to be maintained by wars. Countries that depend on each other economically are less likely to go to war, not wanting to fight with their customers or suppliers. Thus the resulting pain of unemployment is preferable to wholesale conflict.

But are those two observations valid? To assess them, we have to understand our history. War, it is said, is God’s way of teaching Americans geography. Perhaps unemployment is how we learn economics. Are Americans, whose jobs have been shipped overseas, the walking wounded in the war against Marxist totalitarianism? That’s a stretch, but perhaps it will make lawmakers feel better when they vote to cut off unemployment benefits. If you’re keeping score, they can shout, capitalism has defeated communism. We won. Oh, by the way, don’t bother to show up for work Monday.

It’s hard to explain all this to younger Americans, who are generally a hopeful and cheerful lot. It means hinting that a great deal, maybe all, of what they have been taught so far in school is wrong, or at best useless. It means offering a full explanation of human nature, including its awful and miserable characteristics, its meanness and its fearful avarice.

That information is no fun to deliver. The worst human traits should be broken to the young in small pieces, so the facts can be digested and compared with what they already know.

My friend invited me over to talk to his son, suggesting I could explain the new economic realities more clearly than he could.

No, thanks, I said. He’s your kid. You do it.

Jeff Danziger is a political cartoonist and author of “Rising Like the Tucson,” a novel about the Vietnam War.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.