How the bad apples got hired at the Sheriff’s Dept.

- Share via

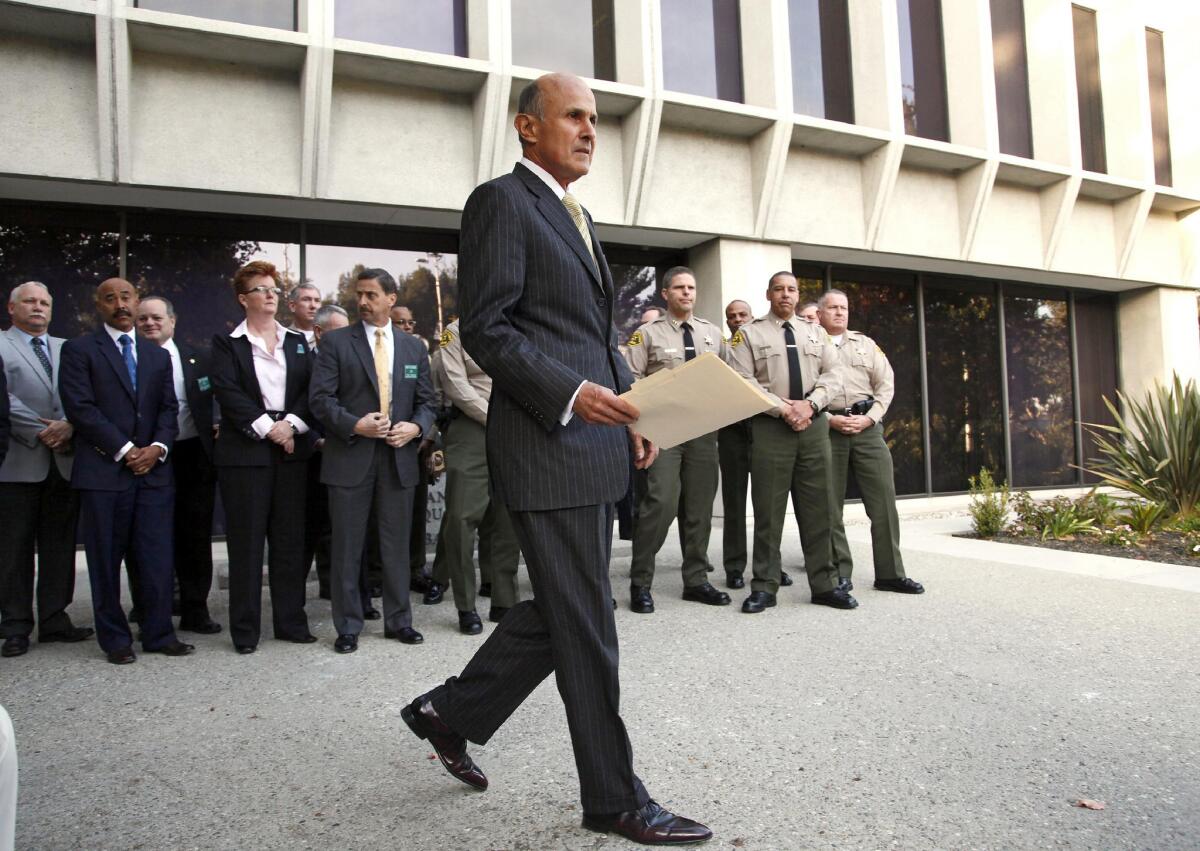

Sheriff Lee Baca had his hands full last week responding to the arrests of 18 of his current and former deputies amid a continuing investigation into abuse of inmates at Los Angeles County’s jails, so let’s hope he hasn’t forgotten that he is due to report today on the previous week’s scandal: the hiring of dozens of deputies with personnel records that showed lying, cheating, excessive force and irresponsible use of firearms.

The two matters aren’t related in any formal sense; none of those arrested Dec. 9 was among the group that moved over to the Sheriff’s Department in 2010 when the county’s public safety police force was dissolved. But it doesn’t take a leap of imagination to recognize a link between bad hiring practices and bad deputy conduct, especially if the sheriff’s hiring of those 280 public safety officers three years ago followed standard policy.

Did it? An understandable assumption in the wake of The Times’ investigation into the backgrounds of the former public safety officers is that something went wrong. Perhaps procedures were temporarily loosened or standards were lowered for this particular group of applicants based on their prior county service. Those are the sorts of explanations the Board of Supervisors is likely seeking from Baca.

SOCAL POLITICS IN 2013: Some rose, some fell -- and L.A. lost its women, almost

But there is also the even more troubling possibility that nothing went wrong at all; or, more to the point, that the sheriff routinely hires deputies who, like dozens of the former public safety officers, are adept at evading polygraph exams, were rejected or fired by other law enforcement agencies, shoot at their spouses in the midst of arguments or pull their county-issued weapons merely to emphasize a point. Instead of being an enormous but one-time flub, the employment of deputies from the defunct county agency could be a window into the sheriff’s regular hiring standards and procedures.

That’s the threshold question: Whether the kinds of problems that ought to make applicants ineligible to carry badges and guns in county service are typical of sheriff’s deputies. The burden is on the sheriff to show that they’re not.

The public has little information about the personnel records of its deputies, so it has a hard time holding the sheriff accountable at election time for his competence at staffing his department. In this case, the egregious instances of alleged and proven misconduct could be reported by The Times only because they were leaked. The sheriff generally keeps such a tight hold on that kind of information that the department’s first response to the story was to launch an investigation into the leak, not the bad hiring.

But the public must have the answer. Without it, it won’t be clear what the problem is, so it won’t be clear how to solve it.

Years ago, the Board of Supervisors established an Office of Independent Review and hired Michael Gennaco to track misconduct and evaluate the sheriff’s internal handling of such matters; and it retained special counsel Merrick Bobb to monitor and report on the Sheriff’s Department. Any full report on the transfer of the public safety officers must necessarily include an explanation of why neither of those two offices learned of the background investigations of the deputies who were hired in 2010.

But that’s perhaps assuming too much. Did Gennaco’s or Bobb’s offices become aware of the problem hires? And if so, why did they not inform the Board of Supervisors? And even that may be assuming too much. It’s a cliche from the Watergate era, but it fits: What did the county supervisors, not just the sheriff, know, and when did they know it? How credible is the assertion that they were unaware of the situation until The Times’ report?

And if they were indeed aware, what action did they take? Was there special monitoring and retraining of the problem officers? Were they restricted to duties that would minimize the danger they posed to the public? Did the sheriff take any steps to reverse the hiring decision? Or did the elected officials just hope against hope that no one would ever find out?

Then, having dealt with those questions, any competent report by Baca or anyone else would deal with the political pressures and dynamics at play. Former undersheriff Larry Waldie — who Baca says was responsible for the hires — was quoted as saying that he was unaware of any problems with these officers. But he also was quoted as saying that he was under “significant pressure” from the Board of Supervisors.

What kind of pressure? Were board members running interference on behalf of any particular applicants? Were they pressing for a larger number of hires at the behest of the public safety officers union? It is not inconceivable that in order to get labor on board with the dissolution of the county police office, there was a promise that most of them would be hired (fewer than one-third of the officers who sought to move over to the Sheriff’s Department were rejected).

Twice this year county supervisors have applied significant pressure to other county department directors to step up hiring. In both cases — with the Department of Children and Family Services and the Probation Department — at least some of the supervisors demonstrated a surprising lack of awareness of the hiring process or an indifference to any lowering of standards that went along with stepping up the pace.

Baca’s early comments have signaled an intention to blame the now-retired Waldie for the hiring and, only secondarily, himself for not second-guessing Waldie. But that’s not enough. The subject of any inquiry cannot be limited to simply what happened in this case but what happens all the time, day in and day out, in county government.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.