Roger Craig, coach who taught split-fingered fastball and pitched for Dodgers, dies at 93

Roger Craig, a well-traveled major league baseball player and coach who became a pitching guru in the 1980s teaching the merits of the split-fingered fastball, has died.

The San Francisco Giants announced Craig’s death Sunday. He was 93.

Craig was the pitching coach of a dominating Detroit Tigers team that won the World Series in 1984, then continued teaching the split-finger as manager of the San Francisco Giants, who won a division title in 1987 and reached the World Series in 1989. A right-handed pitcher, Craig appeared in four World Series during a 12-year career that included seven seasons with the Dodgers in Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Pitchers threw a split-finger by gripping the ball with their index and middle fingers. The result was “a fastball that you put an extra spin on it so that it drops down in front of the batter so fast he don’t know where it’s goin’,” Craig explained to Playboy magazine in a 1988 interview. “To put it in layman’s terms, it’s a fastball that’s also got the extra spin of a curveball.”

UCLA defensive coordinator Bill McGovern died Tuesday at his Southern California home after a lengthy fight with an undisclosed form of cancer.

It wasn’t original. In the 1970s, Bruce Sutter learned the pitch from a minor league coach and became one of baseball’s best relievers. Craig said a former Brooklyn Dodger teammate, Clem Labine, threw a split-finger in the 1950s that was called “a dry spitter.”

But the success of Craig’s students, a mixture of stars and journeymen, turned the pitch into a phenomenon.

“There ain’t no doubt about it — and you can call me cocky — but if it is thrown properly there’s no one living who can even hit it and if they do, it will be a ground ball,” Jack Morris, the ace of Craig’s staff in Detroit, told Sports Illustrated in 1986.

Craig said he taught the split-finger to anyone who wanted to learn, no matter the team. Among the players he showed it to was Mike Scott, who won the Cy Young Award with the Houston Astros in 1986.

When some pitchers throwing split-finger fastballs later came down with arm trouble, Craig defended what role the pitch might have played in any injuries.

“To me you can hurt your arm quicker throwing a slider, curveball, screwball than you can throwing a split-finger,” he told the Boston Globe in 1992. “If you throw it the way I teach it, it’s just like a fastball. All you do is spread your fingers.”

Craig, who never threw the pitch himself during his major league career, started teaching it in 1980 to youngsters at a San Diego baseball school he owned.

“A lot of pitching coaches try to teach you what worked for them,” Dan Petry, who pitched for Craig in Detroit, told Sports Illustrated in 1984. “Roger teaches what’s best for you, possibly because he didn’t have that great of a career.”

Roger Lee Craig was born Feb. 17, 1930, in Durham, N.C. He said he was discovered by baseball scouts in 1949, his senior year in high school, when he filled in for a top prospect who was hurt. The 6-foot-4 Craig went to North Carolina State to play basketball, but quit in 1950 to sign with the Dodgers.

He spent 1952 and ’53 in the Army, assigned to Fort Jackson, S.C., and playing enough baseball that “I matured as a pitcher,” he told The Los Angeles Times in 1959.

Chris Roberts, who called some of the most iconic moments in UCLA basketball history as the team’s play-by-play announcer, dies at age 74.

Craig reached the majors in 1955 and pitched with the Dodgers, New York Mets, St. Louis Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies until 1966. He started the Dodgers’ last game in Brooklyn and was a key pitcher down the stretch in their first Los Angeles World Series title in 1959. He pitched in the World Series in 1955, ’56 and ’59 with the Dodgers and 1964 with the Cardinals.

His career record was only 74-98 but more than 40 of his defeats came in two seasons with the expansion Mets. He was 10-24 in the Mets’ first season in 1962 and 5-22 in 1963, losing 18 in a row.

“Losing was a tremendous influence in shaping my pitching philosophy,” Craig said in “Inside Pitch,” a journal of the 1984 Detroit season he wrote with sportswriter Vern Plagenhoef. “I learned the value of being competitive, regardless of the circumstances. I learned the value of positive thinking and the power of self-esteem.”

Craig coached with the San Diego Padres and Houston Astros and was a minor league manager for the Dodgers before getting his first managing job with the Padres in 1978. He was let go after two seasons but wasn’t out of baseball long. Manager Sparky Anderson, who like Craig grew up in the Dodgers’ system and coached with Craig in the Padres’ first season in 1969, hired him as pitching coach in Detroit.

“The man is a genius,” Anderson told Sports Illustrated in 1984. “He’s so optimistic, he could find good in a tornado.”

Craig retired after the Tigers won the World Series in 1984 but was hired as Giants’ manager to finish out the 1985 season. The positive outlook Anderson appreciated came in handy in San Francisco.

“I’ll never forget Roger’s first day in spring training [in 1986],” Al Rosen, the team’s general manager, told The Times in 1987. “He started telling these guys who were so used to losing that they were going to win. He told them he could see a championship in their future. A lot of guys had heard this before but by the end of the meeting, everyone was sitting up and listening to him in rapt attention. It was pretty impressive.”

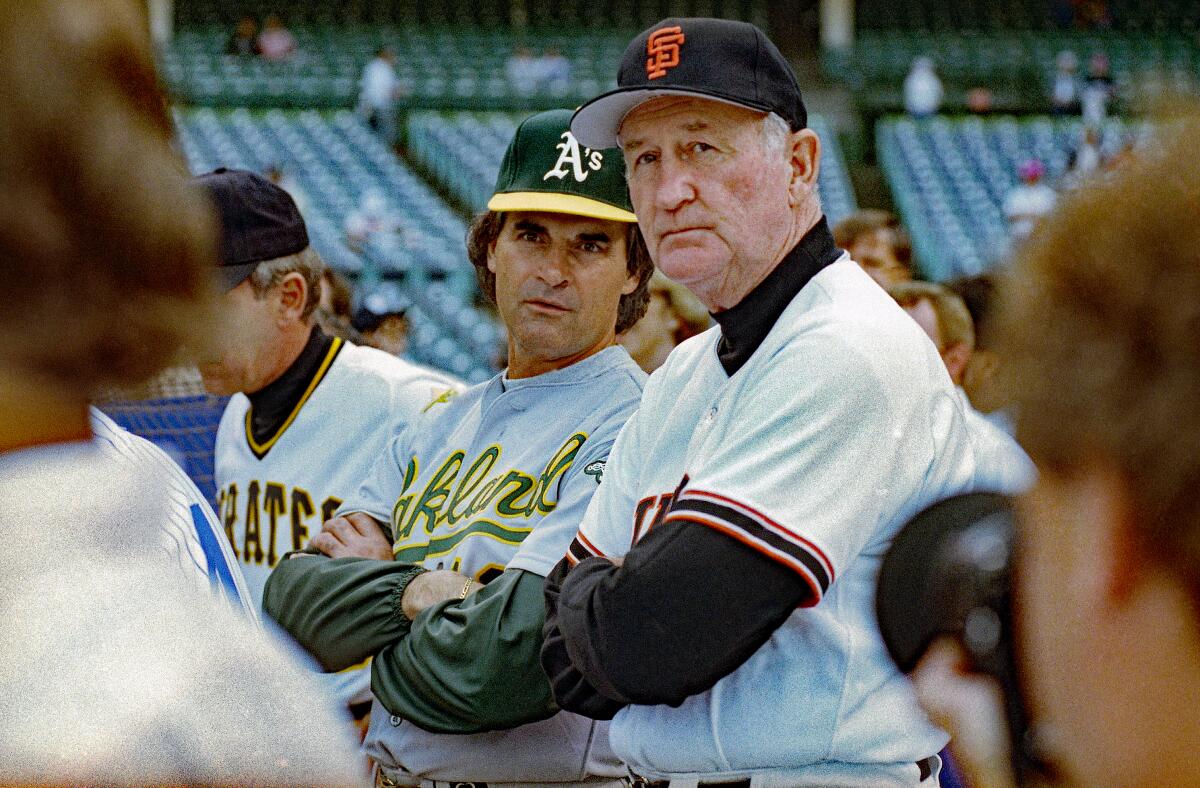

It took Craig two seasons to turn the Giants from a team that lost 100 games in 1985 into the Western Division champions. They won the National League pennant in 1989 but lost to the Oakland Athletics in a World Series best remembered for an earthquake just before Game 3. He was fired after the 1992 season.

“We have lost a legendary member of our Giants family.” Larry Baer, Giants president and chief executive officer, said in a statement. “Roger was beloved by players, coaches, front office staff and fans. He was a father figure to many and his optimism and wisdom resulted in some of the most memorable seasons in our history.”

Craig is survived by his wife, Carolyn; three daughters, Sherri Paschelke, Teresa Hanvey and Vikki Dancan; a son, Roger Jr.; seven grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren, the Giants said in a statement.

As a manager, Craig was known for his unconventional moves, his ability to steal the opponents’ signs and his never-failing optimism. Typically, he saw the Giants’ weather-challenged home field, Candlestick Park, as an advantage.

“We knew the elements, the wind factor,” he told the New York Times in 1987. “And it should help our sinkerball and split-finger pitchers.”

Craig even gave the team a rallying phrase and a marketing tool with his favorite saying, “Humm Baby,” something a Little Leaguer would chant on the field to encourage his pitcher.

“To us, a good fielding play was a humm baby,” Craig told The Los Angeles Times in 1988. “So was a good player, or even a pretty girl in the stands. They still are.”

Thursby is a former Times editor.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.